July has provided many rich and interesting stories I could write about.

There was the Labour leader, Sir Keir Starmer’s ill-judged campaign video in which he and Shadow Foreign Secretary, David Lammy, are filmed walking thoughtfully through the grey corridors of the Holocaust Memorial in central Berlin, ‘a massive faux-pas’ in Germany where such a carefully choreographed and blatant political usage of the site would be a complete and passionate no-no.

Or the contentious mural by the Indonesian art collective, Taring Padi, deemed unacceptably antisemitic and therefore quickly removed from this year’s Documenta international contemporary art fair in Kassel, the director quitting soon after.

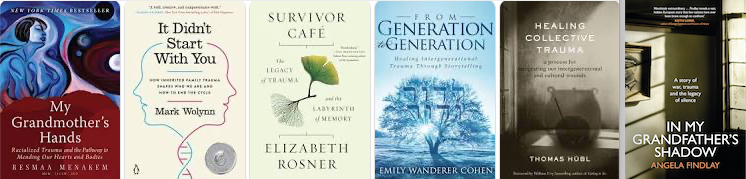

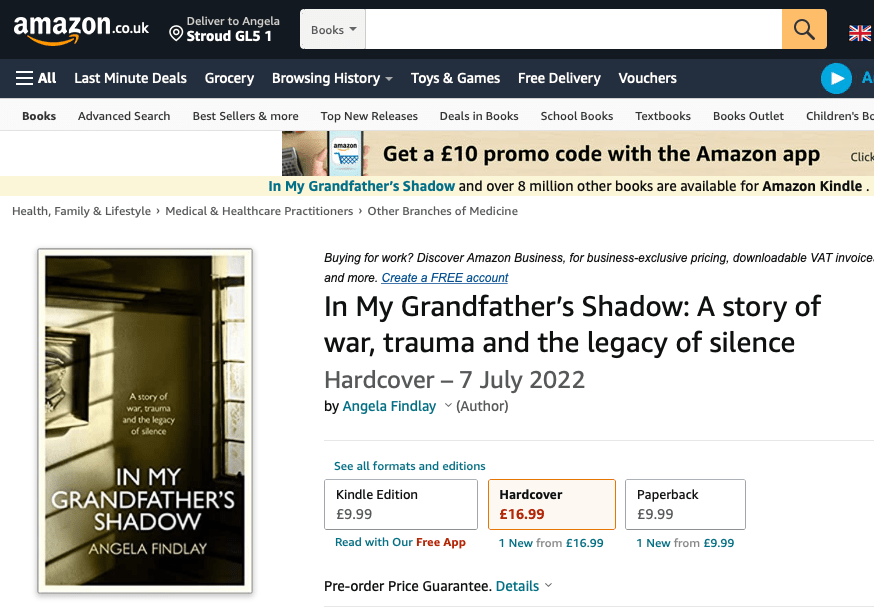

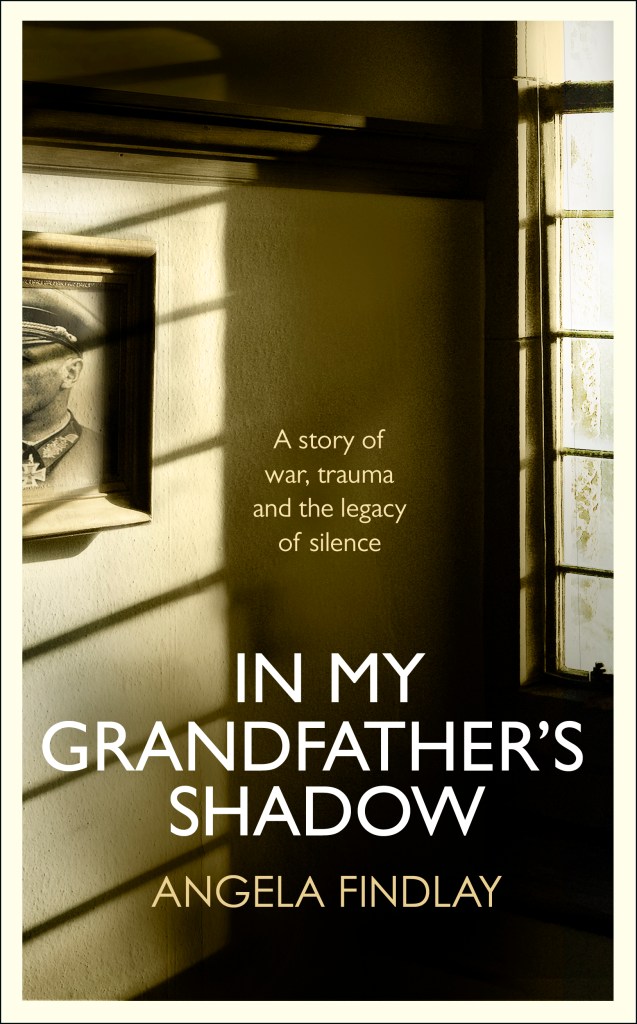

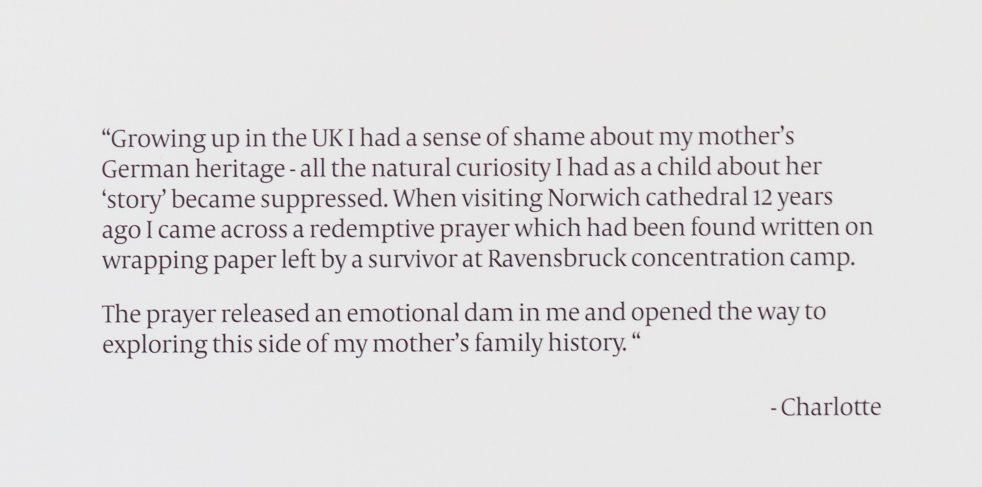

And my personal highlight, the three wonderful book launches that celebrated my arrival at the summit of my endless mountain. July has buzzed with the tangible excitement of people starting to read In My Grandfather’s Shadow and a string of radio interviews (all available here) and future invitations to talk about the themes and questions it raises.

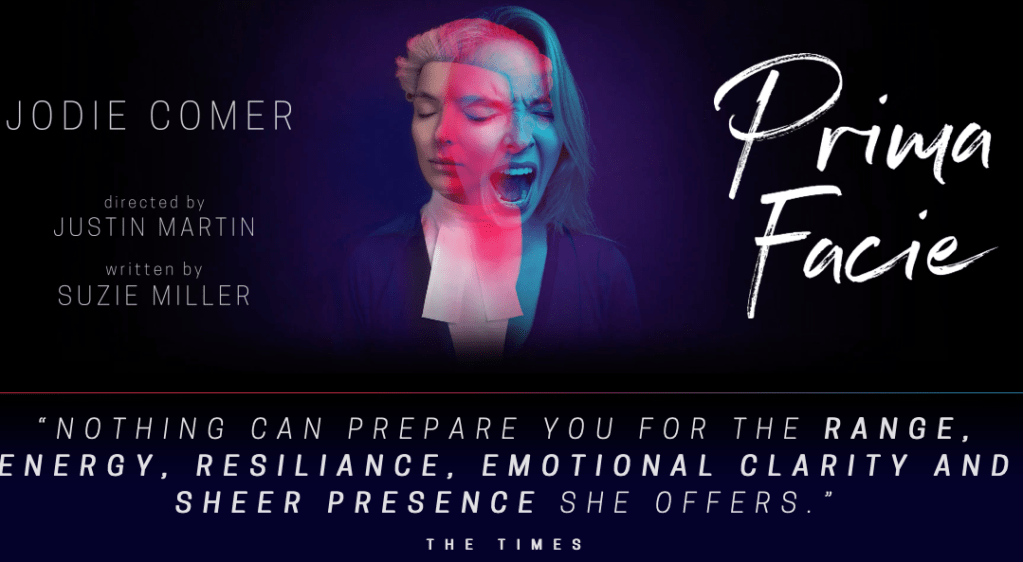

But two other experiences left me reflecting once again on what I see as a fundamental fault line in our troubled world. One was a recent review of my book, In My Grandfather’s Shadow, in the Observer. The other, the National Theatre Live broadcast of Suzie Miller’s award-winning play, Prima Facie in which an outstanding Jodie Comer (the BBC’s Killing Eve’s notorious assassin) plays a young and brilliant barrister who, after an unexpected event, is forced ‘to confront the lines where the patriarchal power of the law, burden of proof and morals diverge.’

In different ways, both the article and the play illustrate the age-old dynamic of ‘feminine’ versus ‘masculine’ perspectives in which the feminine experience is ignored, interrogated until it no can longer stand up and finally overridden, often with catastrophic consequences as the play demonstrates. For example, just 1.3% of rapes end in prosecution. Why? One reason is clear: the clunky measuring tools employed by the law to establish ‘proof’ are wholly inadequate when it comes to female trauma.

On a far less serious level, the Observer review by Matthew Reisz, former editor of the Jewish Quarterly and a staff writer at Times Higher Education, created a similar tension. I am hugely chuffed to have a got a review in the Observer. And there were compliments, like ‘strange and powerful.’ And Reisz was convinced by my hypothesis that a parent’s PTSD can have an impact on a child. Science after all accepts that as real and it’s now mainstream thinking, though it wasn’t always. What Reisz clearly doesn’t give any credence to is the reality, let alone the possibility, of the very premise of the book.

‘Much less plausible,’ apparently, is my belief that I am ‘in some sense haunted by the grandfather she never knew.’ As for the techniques I develop to find an “improbable epiphany” that will help me understand what kind of man he is, well, they are clearly the same “esoteric claptrap” that I suggest my grandfather might have seen them as!

Matthew Reisz has every right to think like he does, and many will agree with him. I am well prepared for this kind of critique. I knew the ‘woo-woo’ stuff (as one or two of my editors called the more weird occurrences) could be problematic for some readers. But I insisted on keeping it. Without it, it was neither my story nor my book. And certainly not my truth. Including a ‘feminine’ perspective on the largely masculine arena of war and traditional fact-based history was for me essential. And I use ‘feminine’ here not as in female, but as in that inner dimension within all of us. That inexplicable world of instinct, intuition, serendipity, dreams and the invisible whisperings of the dead; often the source of creativity or vision, yet also the areas of human experience so often dismissed as ‘dippy-hippy nonsense,’ not ‘real’ or valid because they are ‘unprovable,’ or apparently just ‘wrong’. For it was these things – not clever science or psychologists – that provided the clues to solving the mystery of what I was experiencing.

The book is intensely personal. But the issues it explores – addiction, shame, trauma, inherited guilt, forgiveness, reconciliation – are not. As Prima Facie so dramatically shows, they require a different approach to the logic and plausibility of left-brain thinking. This is what I feel Reisz unfortunately misses. In his final sentence, he reveals the source of his unsettledness in the apparent contradiction of ‘a woman who has dedicated her book to “all those whose lives are affected by discrimination, oppression or war” searching so desperately for redeeming qualities in a decorated Wehrmacht general.’ Is he suggesting there couldn’t possibly be any while misunderstanding my desire to comprehend a relative as wanting to exonerate them?

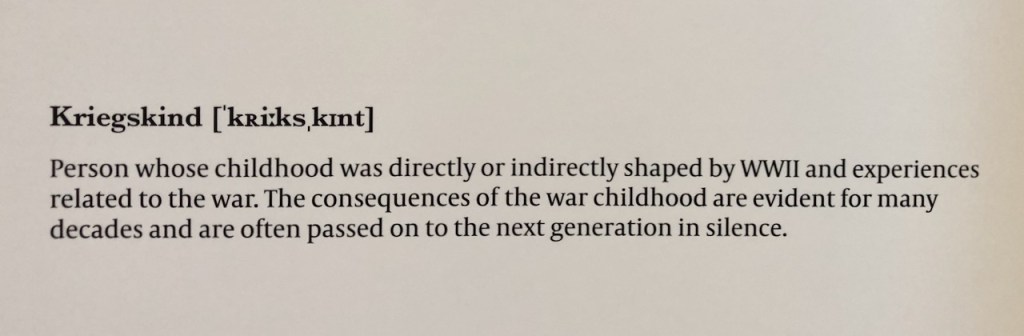

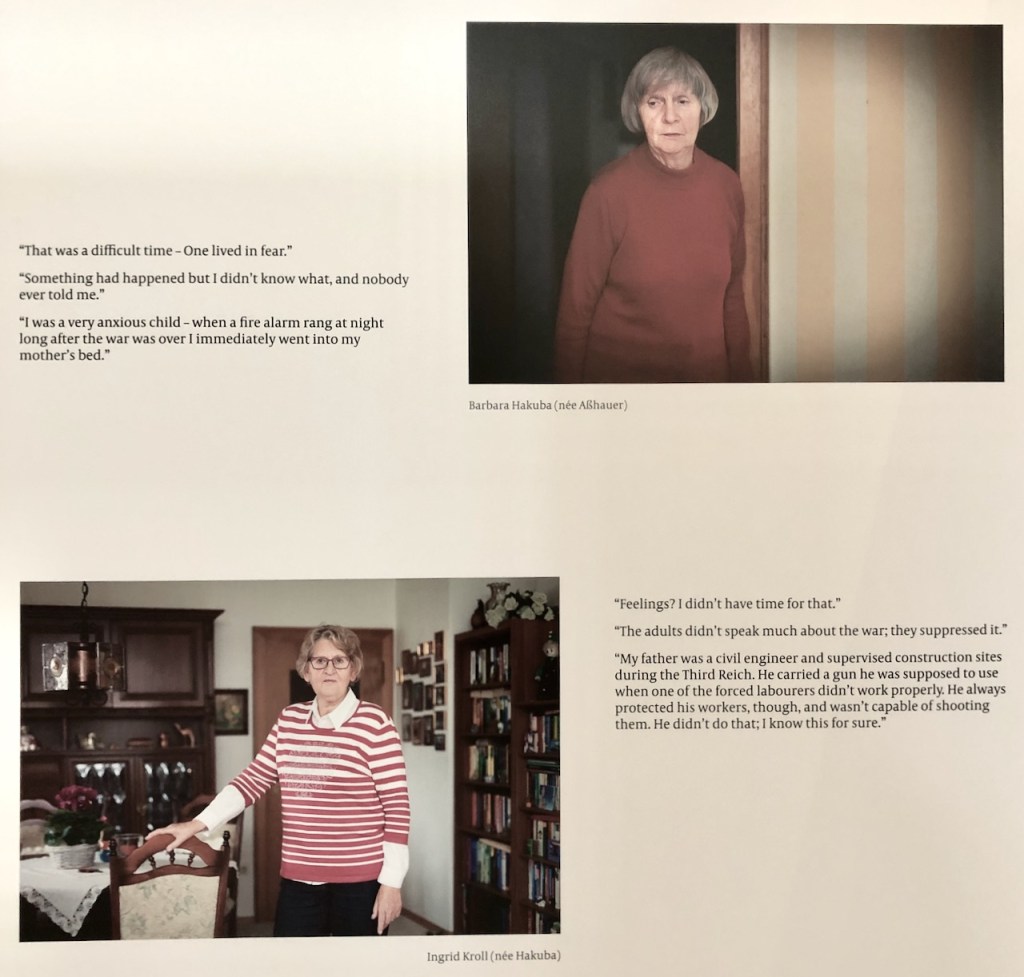

It’s going to be so interesting hearing different responses to In My Grandfather’s Shadow and coming into dialogue with others about their own relationships to the darker corners of their heritages, which is what frequently comes up. Like the prisoners in my art classes, like audience members at my lectures, people begin to talk when you make it safe for them to do so. That’s what I hope telling my difficult story will encourage: conversation. Not about provable facts, but fears, feelings and experiences. Conversation. Not with a goal of judging or a need to be right. Certainly not doubting or questioning the reality of what is being said. Just from a genuine desire to understand others. That’s how we can find our shared humanity.

So just to finish with a bit of undiluted ‘woo-woo,’ I found a 4′ grass snake in my hall a week or so ago. A Stroud friend told me that when animals come into our houses, they have a message. I thought no more about the symbolic significance of a snake. But then yesterday, without me mentioning the snake, another friend reminded me of the questions asked in Goethe’s beautiful story, The Fairytale of the Green Snake and the Beautiful Lily in which the snake sacrifices itself to bridge the divide between the land of the ordinary senses and the land of the spirit or soul. It roughly translate as:

‘What is more precious/glorious than gold?’ asked the King.

‘Light’, answered the snake.

‘What is more refreshing/quickening than light?’ asked the King.

‘Conversation’ said the snake.