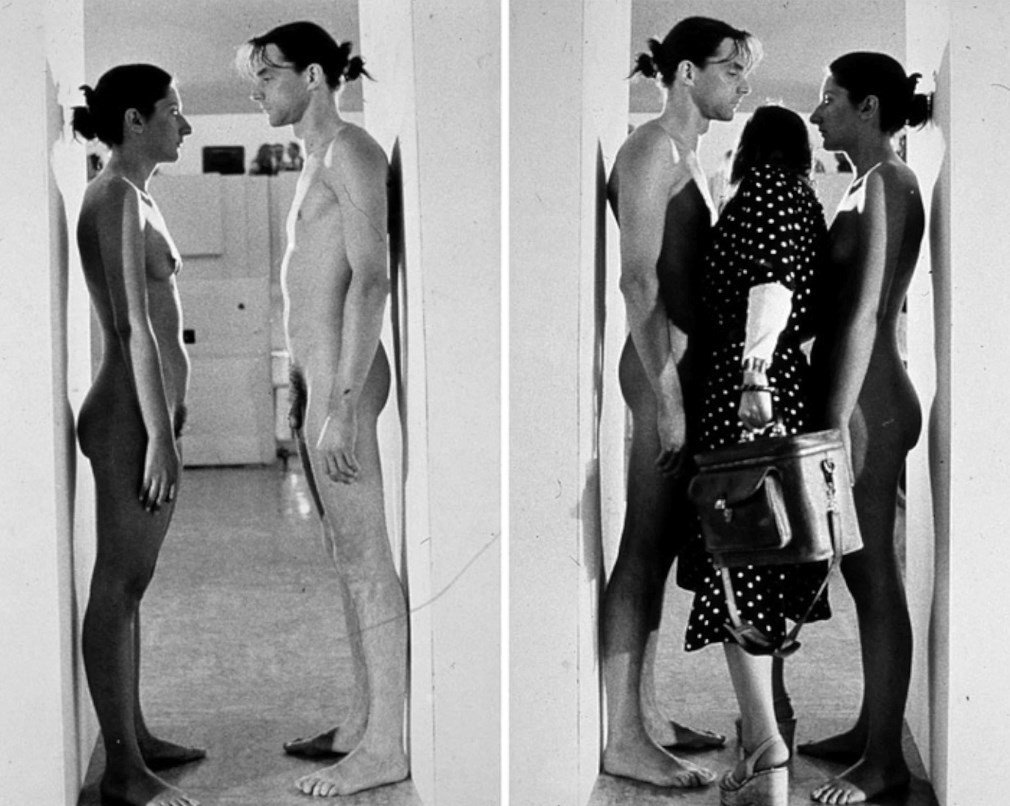

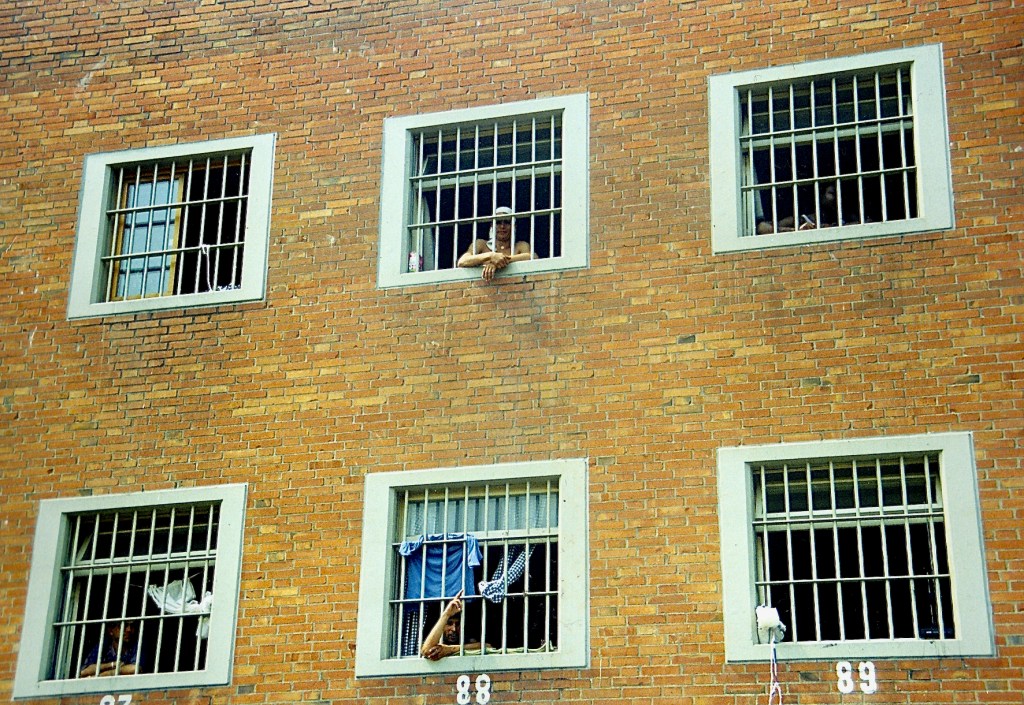

There was something deeply familiar about the process of entering HMP Wandsworth last week. The first time I was there was in 2003 in my role as Arts Coordinator for the London-based Koestler Arts. I had founded the Learning to Learn through the Arts scheme a year earlier and was co-facilitating a 4-week dance and art project called Beyond Words.

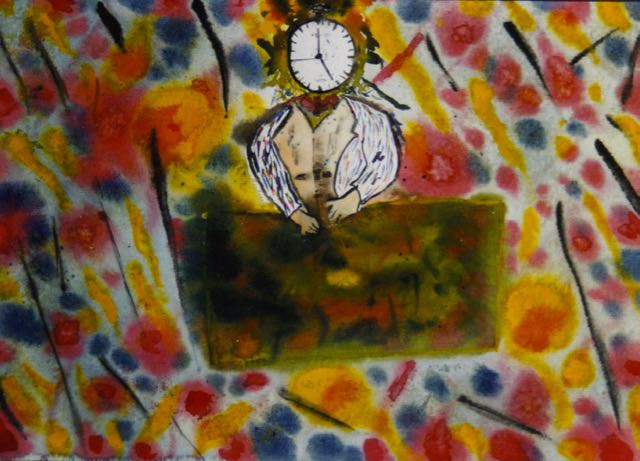

The aim was to bring dance and painting together to create a non-verbal language through which prisoners could express themselves. Each day was a mixture of individual and group exercises that saw the men clambering over tables and chairs to dissolve the formalities of a traditional classroom or splattering paint on paper with Expressionist vigour. Both approaches eventually led to solo multi-media performances and the development of communication skills, camaraderie, trust and sensitivity within the group.

Now, twenty years later, I was re-entering HMP Wandsworth, but this time in the wholly verbal capacity as author of In My Grandfather’s Shadow.

For people who haven’t experienced it, entering a prison can seem synonymous with entering hell. And for many, it probably is. This blog therefore feels unintentionally apposite to Good Friday, the day in the Christian calendar that signifies the crucifixion of Jesus Christ and his descension into hell. We have grounds for this picture of infernal misery from exposure to BBC programmes such as Prisoner, Time, Disclosure: Prisons on the brink. Or five series of Prison Break. But my visit couldn’t have felt further from those dark scenes.

The beautifully organised event was the result of a brilliant collaboration between the Wandsworth Prison Library team and the charities Give a Book and Prison Reading Group (PRG). Generous book donations came from Penguin Transworld and Radio Wano, the prison’s in-house radio station, took care of publicity. I knew from experience how difficult arranging such events can be. Months of dialogue and organisation can be kiboshed by any number of unforeseen occurrences, or simply by time-poor officers’ inability to deliver the prisoners to the room.

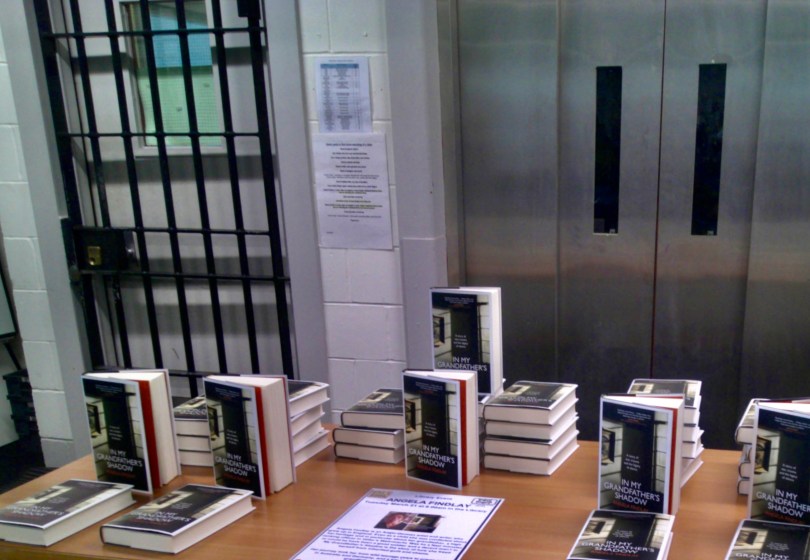

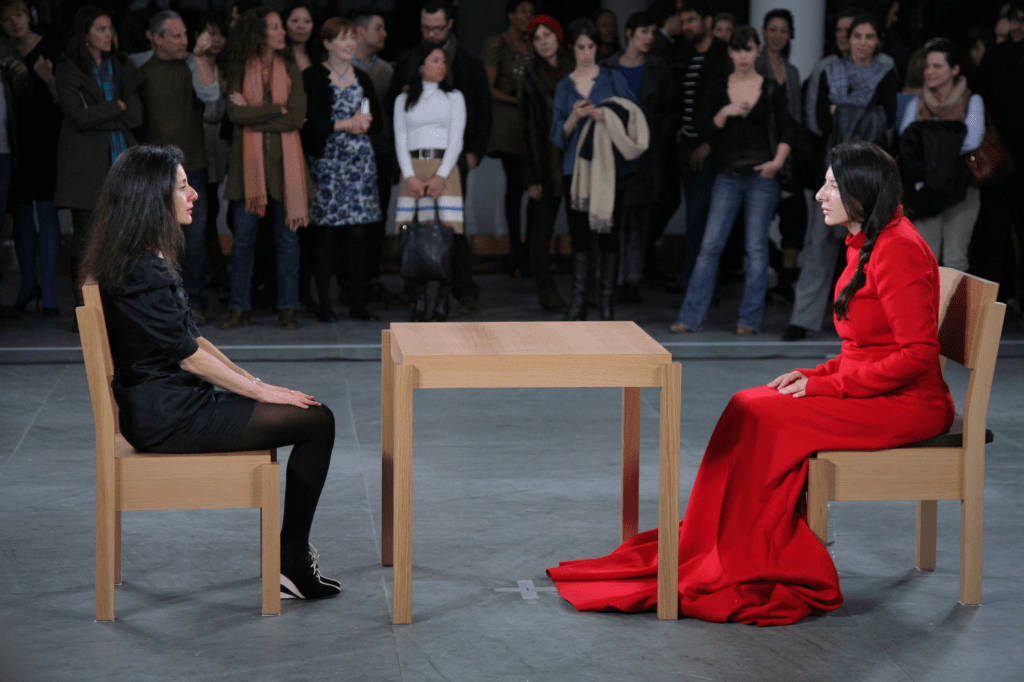

Not on this occasion though. Thirty-five men, mostly already seated, some with copies of my book on their laps, awaited us as we took our seats in front of a display of hardback copies that rivalled any book festival’s. Unlike my regular illustrated talks in which a series of images ties me to a certain chronology of thought, I was able to speak freely, engaging the antennae grown over years working ‘inside’ to gauge the interests and sensitivities of my audience. As I spoke into the men’s intense attention, I sensed cogs turning in brains as they connected my words to their personal situations. So many of my book’s themes speak to their experiences of trauma, addiction, conflict, violence, guilt, shame, depression, intergenerational family legacies…

Like a muscle memory, my heart opened as they began to engage verbally, asking questions and contributing informed opinions and philosophies of their own to mine. One of the librarians said to me afterwards, ‘They are so deep.’ And yes, their questions dived in at the deep end, not dissimilar to audiences in Germany. Intelligent. Philosophical. They know darkness. And they recognise how you get there. What I, as always, hoped to show was a way out.

At one point, as I related how I had felt ‘at home’ in prison as a young woman, a prisoner suggested that it may have been because they are at the bottom. ‘We are the bottom of society.’ He was right. That is the perception of many. Shame is the ultimate bottom dweller of emotions. And in feeling shamed as a teenager for being half-German, I would have related well to those who resided at ‘the bottom’.

I cannot, however, see these men – and I say men as a generalisation because 95% of the prison population is made up of men – as genuinely being at the bottom of the human pile. It is wrong of society to simply clump them together into one unnuanced band of criminal brothers. There are of course some horrendous crimes. But each person is both individual and potentially so much more. Each has a story, a journey of how they got here. And dreams for something different.

One man revealed he had thought about writing his story but felt nobody would be interested. ‘What makes you think that?’ I enquired. ‘Because it would be too dark,’ he replied only to be refuted and encouraged by others with claims that the crime thriller is one of the most popular genres.

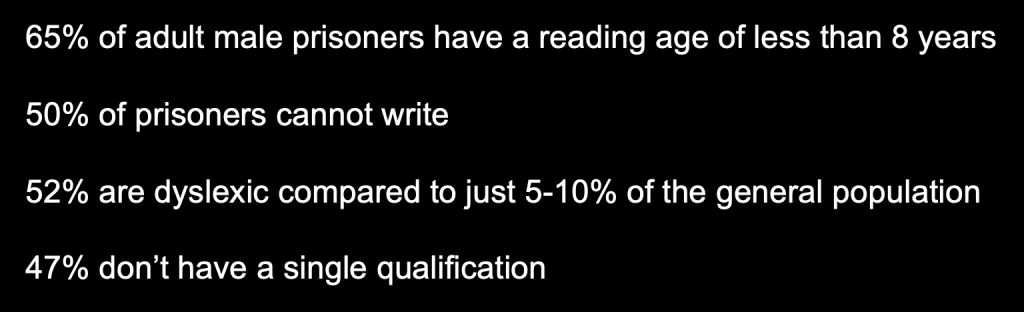

Listening to and briefly meeting the prisoners at this library event didn’t appear to correspond to the prison statistics I regularly quote in my Art behind Bars talks.

A 2022 government review of reading reported: “The most recent data published by the Ministry of Justice shows that 57% of adult prisoners taking initial assessments had literacy levels below those expected of an 11-year-old.” There is nothing new here, but they remain shocking statistics. And yet my experiences tell me that in spite of high rates of ADHD, illiteracy, dyslexia, prisoners are far from ‘thick’ or even uneducated. They may have failed in or been excluded from mainstream education, but all too often that is because they have not received an education appropriate to their learning styles or needs. It’s an education that doesn’t recognise or value what their experiences have taught them about life.

Once the discussions were over, a long queue lined up for signed copies dedicated to names that revealed the audience’s colourful cultural mix. Many imparted tantalising snippets that hinted at reasons for their interest in my subjects… they were from Poland; they were fascinated by alternative perspectives on WW2; they now recognised how their actions might impact their children; they longed for intellectual stimulus.

The importance of the work of HMP Wandsworth’s Library – headed by Beverley Davies and her Senior Assistant, Hannah Pickering (who was taking the photographs) – and the work of Give a Book, PRG and their reading group volunteers plus all the Arts Projects taking place in prisons around the country cannot be underestimated. I am so grateful for and heartened by it. Traditional classroom settings are not always the way to educate people. There are other ways to inspire minds. As Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote in Citadelle:

If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up the men to gather wood, don’t divide the work and give orders.

Instead, teach them to yearn for the vast and endless sea.

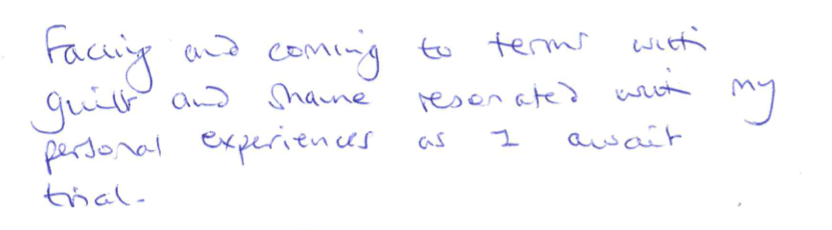

Last week’s Library Event seemed to do just that as both the below comments from the Library and Prisoner Nr. XXX reveal:

“The guys were really buzzing afterwards, and it was great that other people noticed what was going on and wanted to get involved. All the books were taken which is a real positive.”

Prison Reading Group was founded in 1999 by Jenny Hartley and Sarah Turvey. Together with the team from Give a Book and Director of Projects Mima Edye-Lindner, they delivered 5000+ books to 84 groups in 64 prisons.

If you would like to support them, please go to their websites: https://prisonreadinggroups.org.uk