I am not a huge fan of Christmas, but I do love the peace of the days that follow the rush and stuffing of stockings, fridges and bellies. A stillness descends as exhausted people navigate the aftermath of families, toy-strewn floors and overflowing bins. Finally, those of us in the northern hemisphere can follow winter’s call to slow down, rest, and listen to the wisdom of our hearts and souls before the new year draws us back into action.

Peace is not something we can take for granted anymore. Fighting – with words, ideologies or weapons – has increasingly become the norm. We have just been told by the UK defence minister, Al Carns, that “the shadow of war is knocking on Europe’s door.” And warned by NATO boss, Mark Rutte, that “we must be prepared for the scale of war our grandparents and great grandparents endured.” In this year marking the 80th anniversaries of the end of the Second World War, I’ve been asking myself: how do we maintain peace in a world in which so many of the vows and institutions created to prevent future wars are under threat? How do we ensure that ‘Never Again’ still holds? Various recent events have been shaping my thoughts.

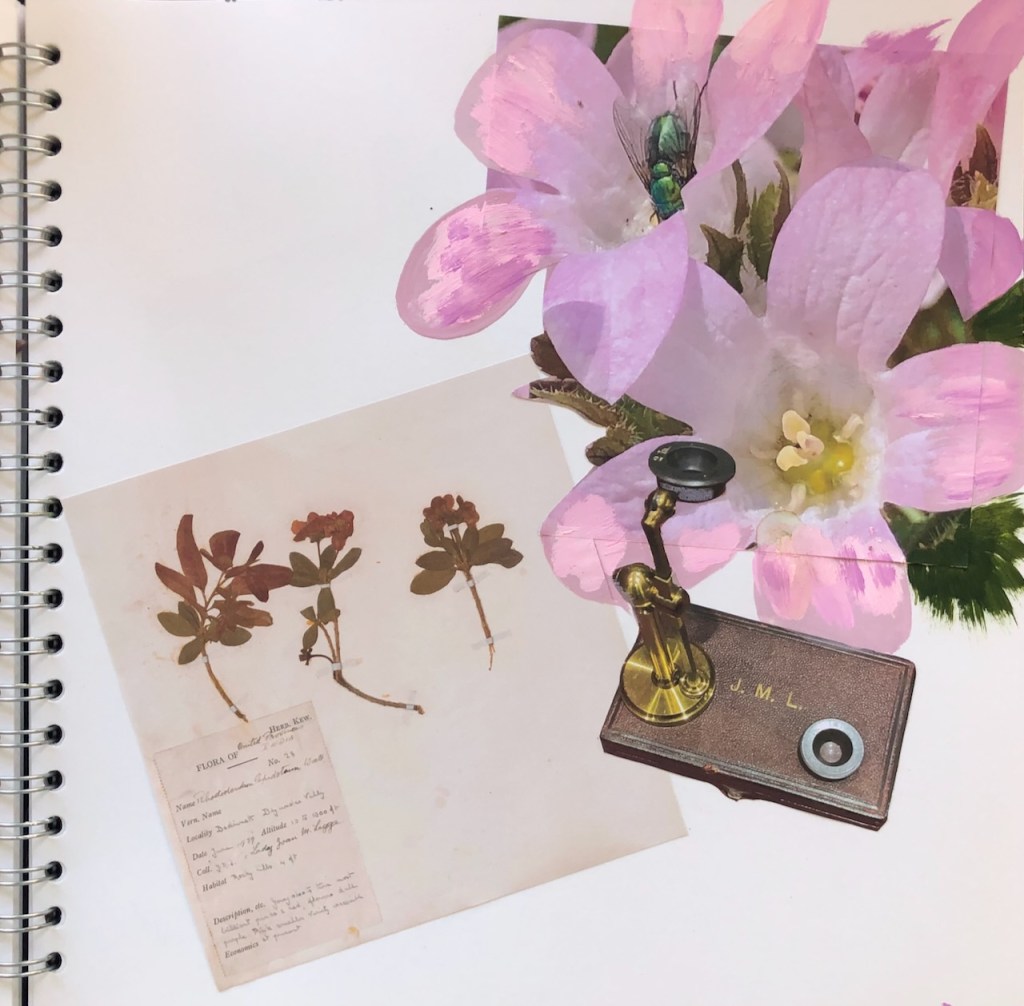

In early December, the German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier and his wife, Elke Büdenbender, embarked on a three-day state visit to the UK, the first in 27 years. In his speech at the state banquet hosted by King Charles III and Queen Camilla, Steinmeier highlighted the deep connections between Britain and Germany; how traditions from each country have been woven together so tightly that their origins are now obscured. Not least among these is the Christmas tree. The first one was displayed in Windsor in 1800 by the German Queen Charlotte, wife of King George III, and the custom soon spread to living rooms across the UK. The same is true for Battenberg Cake – a story I love and have often told in my work (see my December 2017 blog).

On the final day of his visit, President Steinmeier travelled to Coventry Cathedral. He and his wife were greeted by His Royal Highness The Duke of Kent who, among his other roles, is Patron of The Dresden Trust. Coventry and Dresden have been twinned since 1959, linked both by the devastation of the bombing raids each country inflicted on the other, and by the many decades of peace and reconciliation work that have followed.

At around the same time, I had been sitting in one of Goalhanger’s recording studios. You may know them for some of their most popular podcasts in The Rest Is… series, including the chart-topping The Rest Is History and The Rest Is Politics. I was there with Henry Montgomery to talk with historian and broadcaster James Holland, and comedian and ‘Pub Landlord’ Al Murray, on their equally popular WW2-focused podcast, We Have Ways of Making You Talk. Henry, also the grandchild of a high-ranking army officer – in his case the British field marshal best known as ‘Monty’ – and I had previously spoken together on VE Day at the National Army Museum. As I have mentioned in other blogs, we are exploring from our different perspectives how well Britain’s remembrance culture is really working. With ever fewer World War veterans and first-hand witnesses still alive to warn us of the horrors and futility of war, is it doing enough to keep “Never Again” a lived reality?

When I look at the visuals of Britain’s remembrance culture that make it into the media – for many people, perhaps the only occasions where they will actively ‘remember to remember’ the lessons of history – I fear we are not going far enough. We see mostly men in dark coats laying wreaths and solemnly reaffirming vows to uphold the peace and international friendship while elsewhere in the world other men stubbornly refuse to make it. We see the bright regalia of royalty and the glinting medals of veterans. It is the language of the military and the state: formal, symbolic and carefully choreographed. All fine and important. But peace is not confined to grand stages or organised occasions.

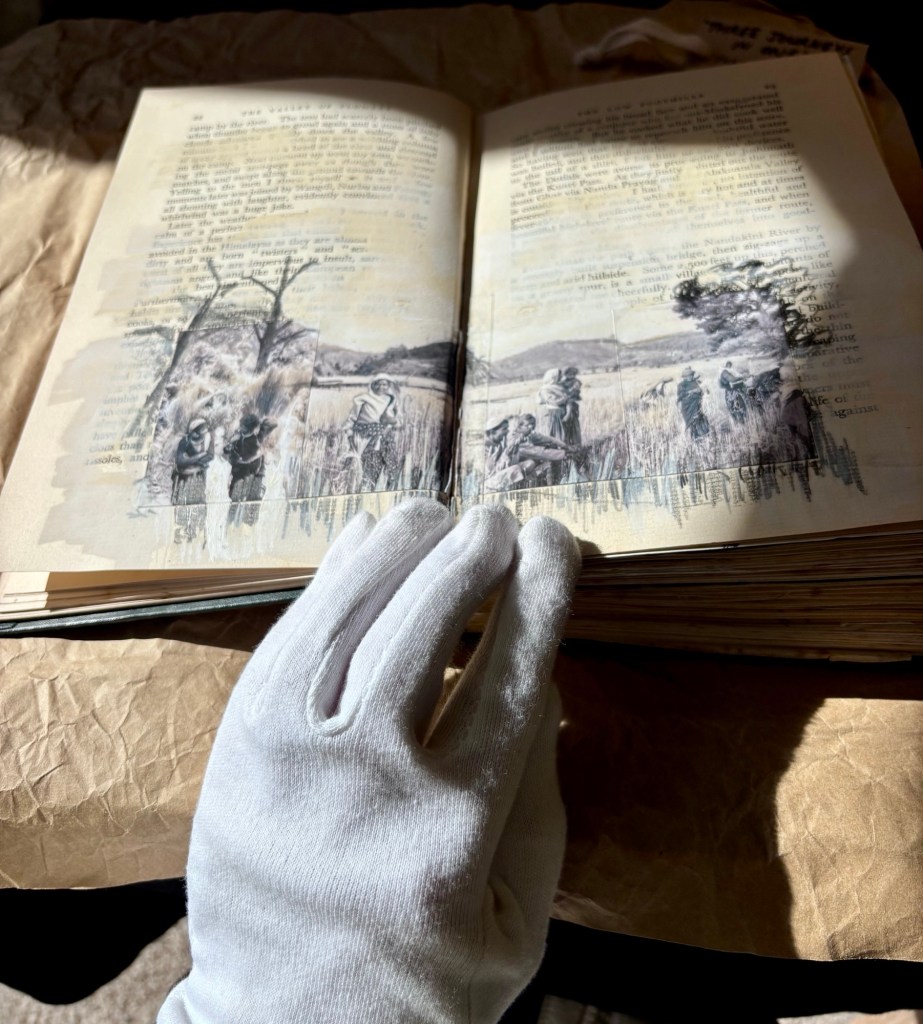

Listening to Radio 4’s brilliant Reith Lectures, this year titled Moral Revolution (what could be more pertinent in our times?) and delivered by the historian and author Rutger Bregman, I was struck by a description of a Quaker practice to bury the dead in unmarked graves. In stark contrast to the fields of Commonwealth War Graves and annual remembrance rituals, they believe you don’t honour people with costly headstones but with actions. Thomas Clarkson, the famous abolitionist who wrote extensively on the Quakers, said: If you wish to honour a good man, let all his actions live in your memory so that they may constantly awaken you to imitation, thus you will show that you really respect his memory.

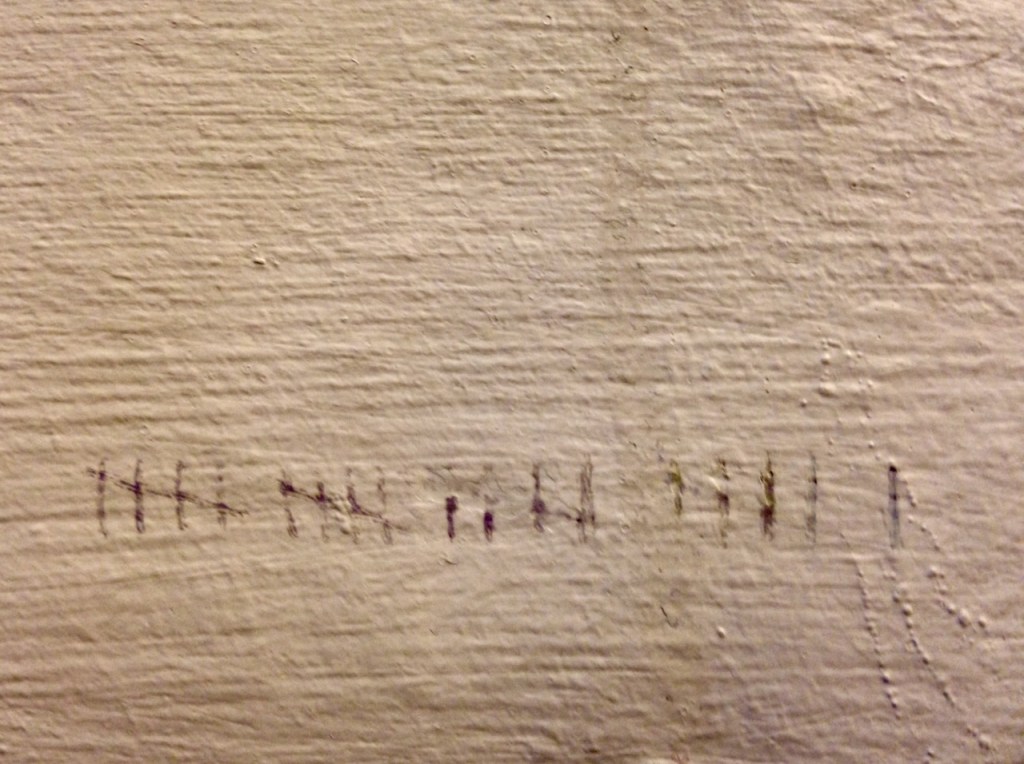

In a similar vein, Germany’s counter memorial movement, which began in the 1980s, fundamentally changed the dynamics of memorialisation. Through its shifting, disappearing monuments and memorials to absence, the focus turned toward the millions murdered by the Nazis. Responsibility for remembrance and for ensuring such destruction never happens again was transferred from stone and bronze into the hands of ordinary people.

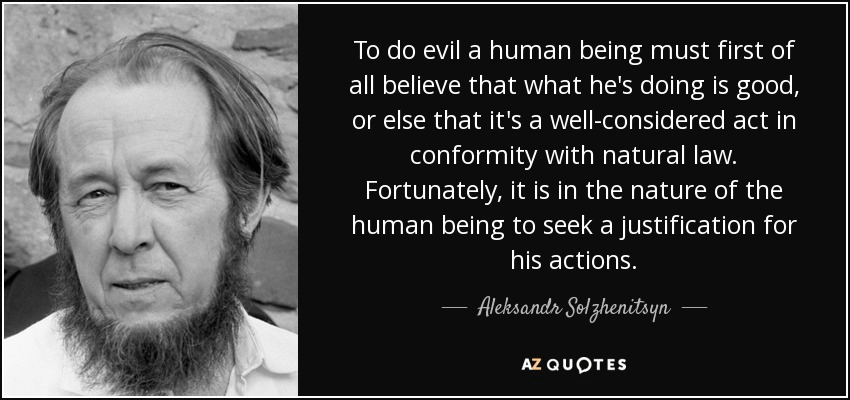

And that is where it belongs. Peace is sustained not only by treaties, leaders and ceremonies, but by us – each and every one of us in our daily lives.

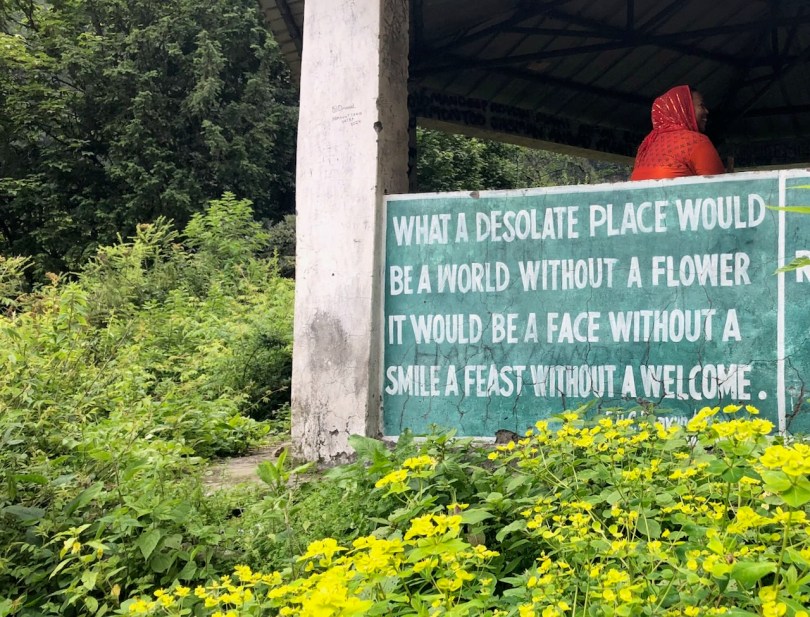

So if, like Rutger Bregman with his call for a Moral Revolution, we were to start a Revolution of Peace, what might it look like? What would its optics be? What language would it speak and who would embody it? I suspect it would be a revolution that brings heart, warmth, listening, sharing and art into our everyday encounters. One with no emphasis on sides and differences, winners and losers, no interest in egos, power games or deception. Idealistic maybe, but arguably closer to what is naturally human for many of us than conflict and war.

Perhaps over Christmas we can practice peacekeeping: at kitchen tables, in disagreements, in how we speak to one another and how willing we are to listen. In choosing curiosity and compassion over judgment. In noticing where hostility quietly creeps into our own lives and questioning the ingrained narratives that divide the world into a good and right ‘us’ and a bad and wrong ‘them’.

When peace is on the line, remembrance must shift from an act of looking back to a commitment to shaping the future. Just as conflicts and wars escalate out of countless small decisions, so peace does too. May we – and the world’s leaders – choose peace in the year ahead.

But first, let the mayhem continue… Wishing you all a very happy festive season, a meaningful Winter Solstice, a restful and restorative break and, in 2026, peace on earth and goodwill to men… and women.

The We have Ways… podcast episode is due to be published on 30th December in all the usual podcast outlets.