“I think you’ll like this,” a friend said unloading a hardback the size and weight of a breeze block. Slightly daunted and clueless about the rebels of its title, it sat atop the leaning tower of my bedside book pile. When I finally picked it up, I couldn’t put it down.

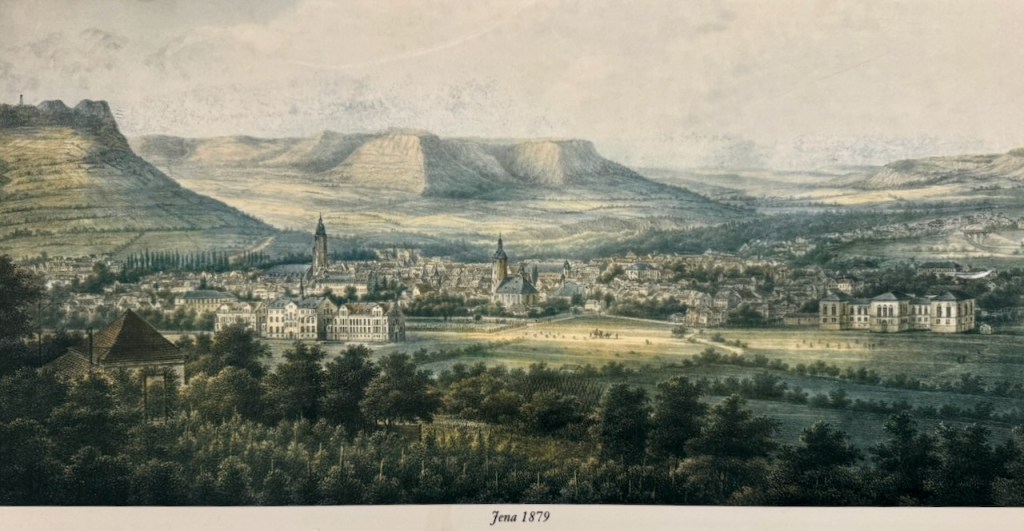

Magnificent Rebels by Andrea Wulf transported me to the small university town of Jena (pronounced ‘Yain-a’) near Weimar, where, between 1795 and 1803, a group of brilliant minds coalesced and forever changed the world.

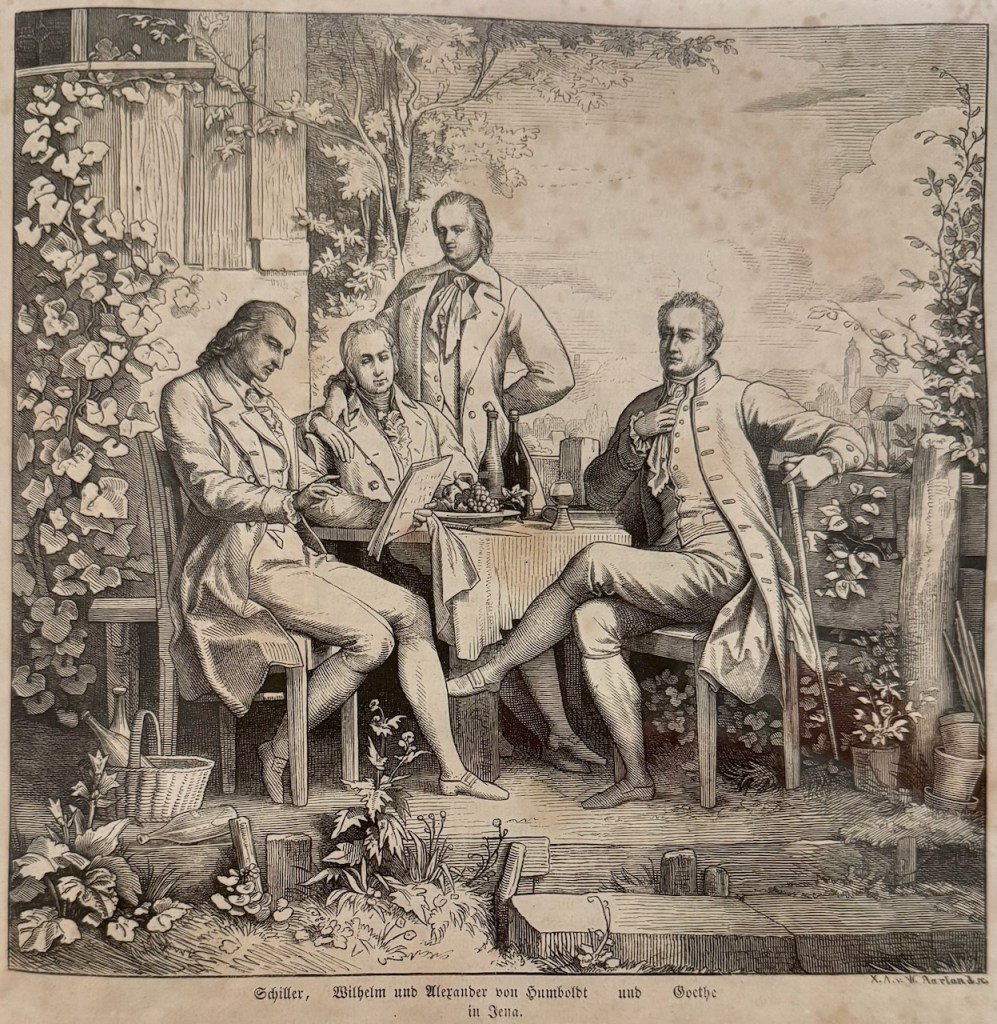

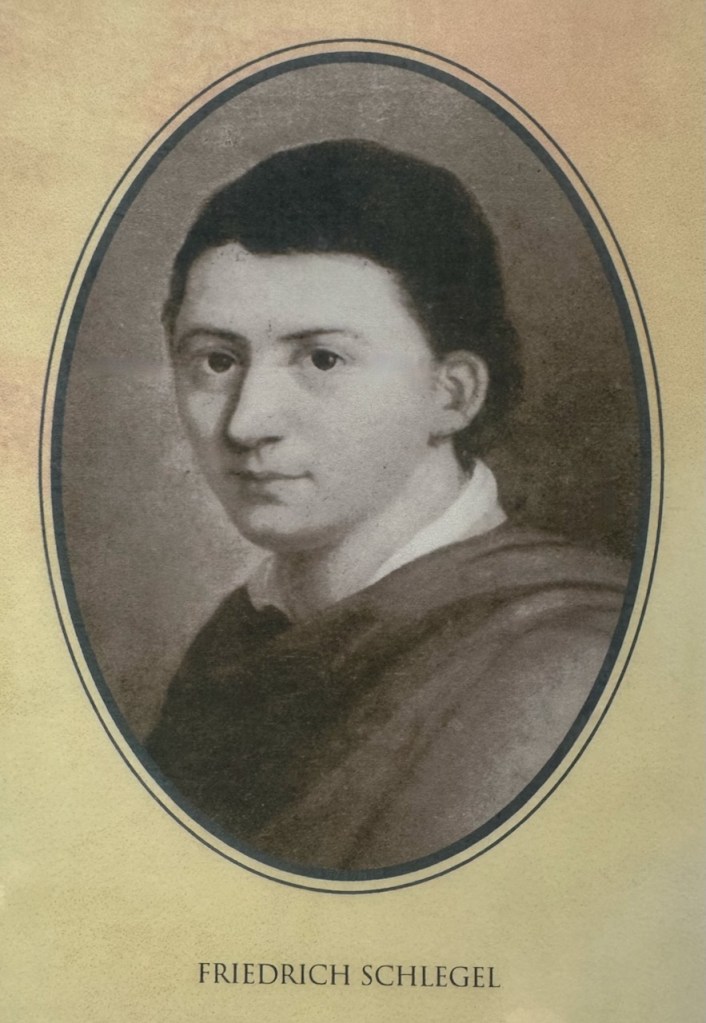

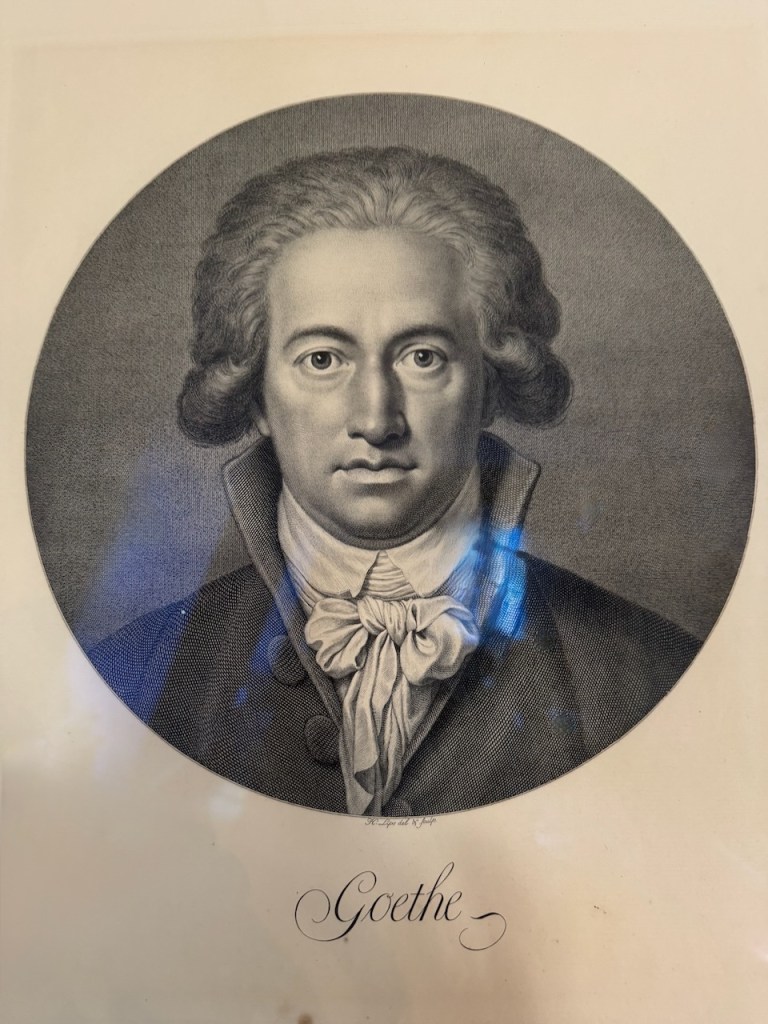

Known as the First Romantics, they were far more than the modern associations with sentimentality and solitary figures in idealised landscapes. This group of Germany’s brightest poets, philosophers and scientists – Goethe, Schiller, Kant, Fichte, Hegel, Novalis, the Schlegel and von Humboldt brothers, Schelling, and their wives – rebelled against the fragmented, rationalised worldview of the Enlightenment. Against the backdrop of the French Revolution and Napoleon’s armies, they revolutionised thinking, paving the way for modernity, the liberation of the Ich (Self), and the idea of free will.

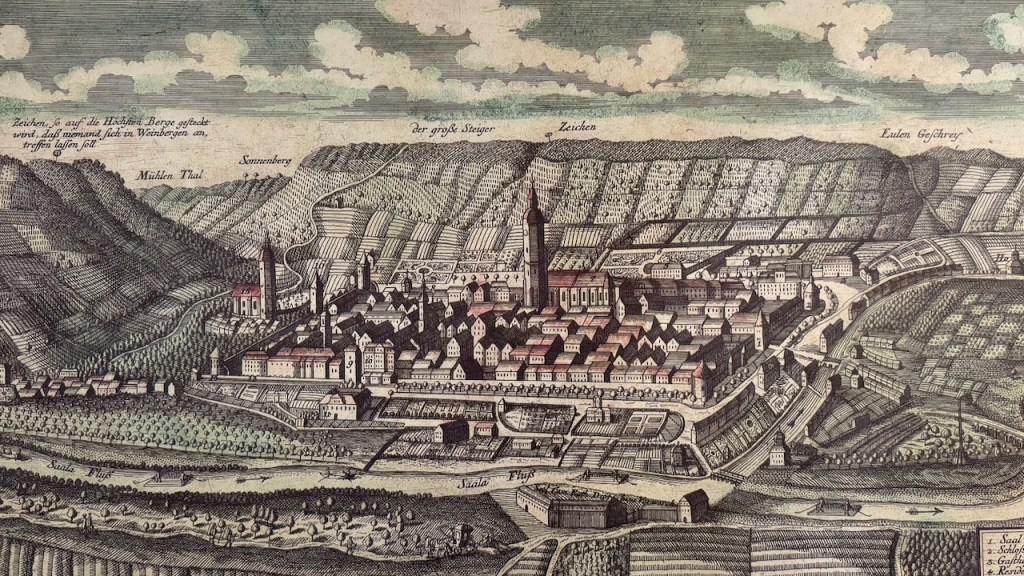

Jena lay at the heart of the Holy Roman Empire, which was neither Holy nor Roman but encompassed much of present-day Germany. Its university was governed by four Saxon rulers from different duchies, making rules difficult to enact and enforce. Escaping the censorship other universities faced, it became more progressive and open-minded than anywhere else. So while England, Spain and France turned outwards towards colonies and the United States, Germany remained inward-looking. With 40 universities (compared to England’s two) books were everywhere, fuelling imaginations and breaking new ground in people’s internal worlds.

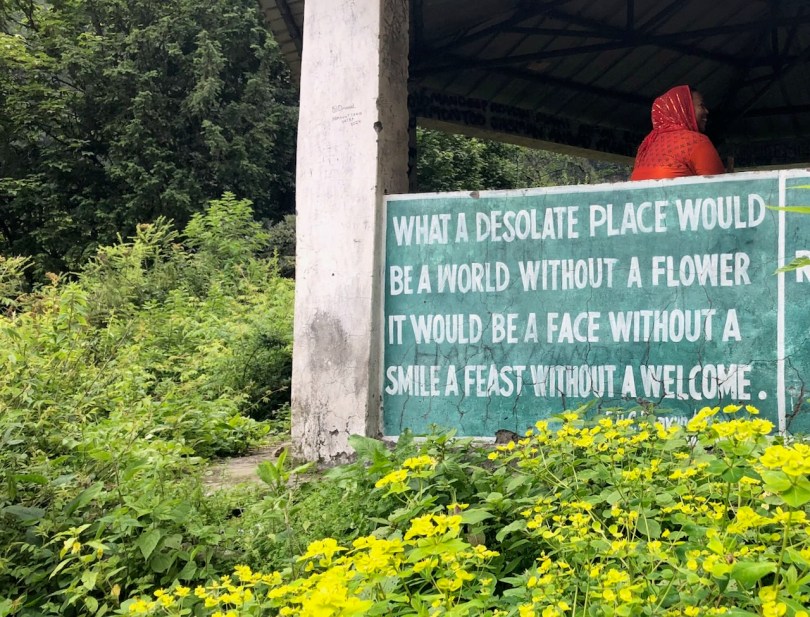

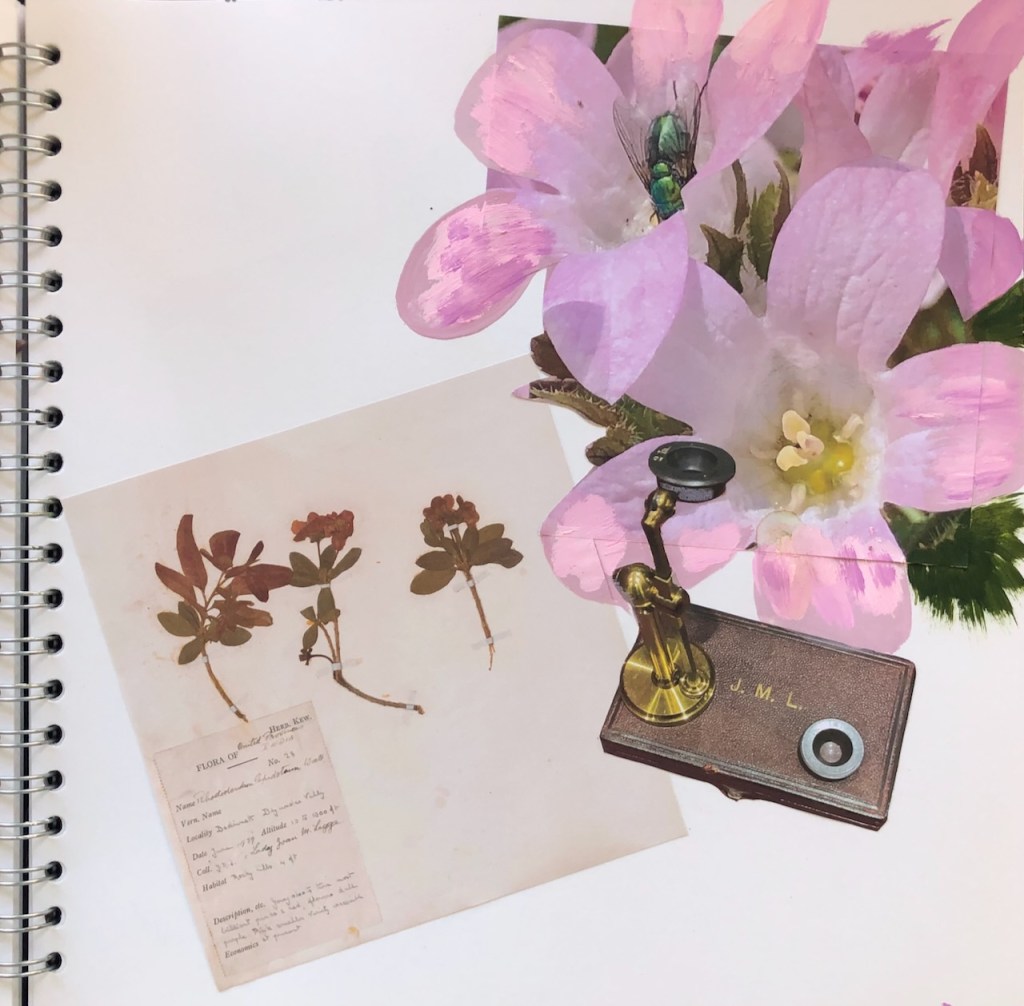

With the liberal-minded intellectual Caroline Michaelis-Böhmer-Schlegel-Schelling (she married three times!) as the beating heart of the group, the Jena Set sought to poetise the increasingly mechanical world. They tore down boundaries between the arts, sciences, nature and the divine, weaving them together into a new reality. This recognition of the interconnectedness of all disciplines, with the Self and the arts as sense-makers of the world, ignited something in me, just as it had for many others both during their lifetimes and over the following two centuries. In our increasingly technicalised world, their conception of the world feels more relevant than ever.

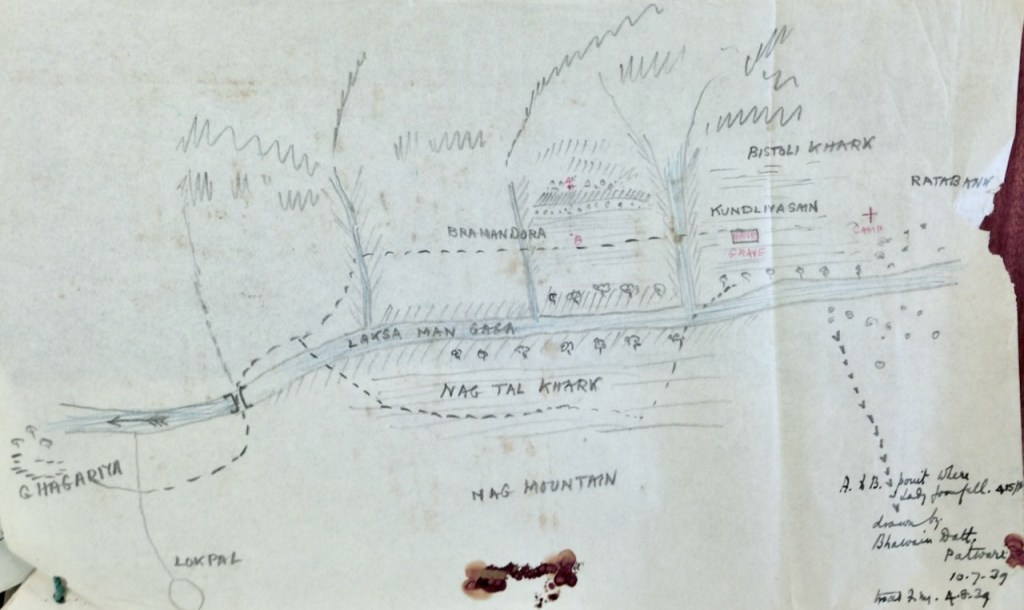

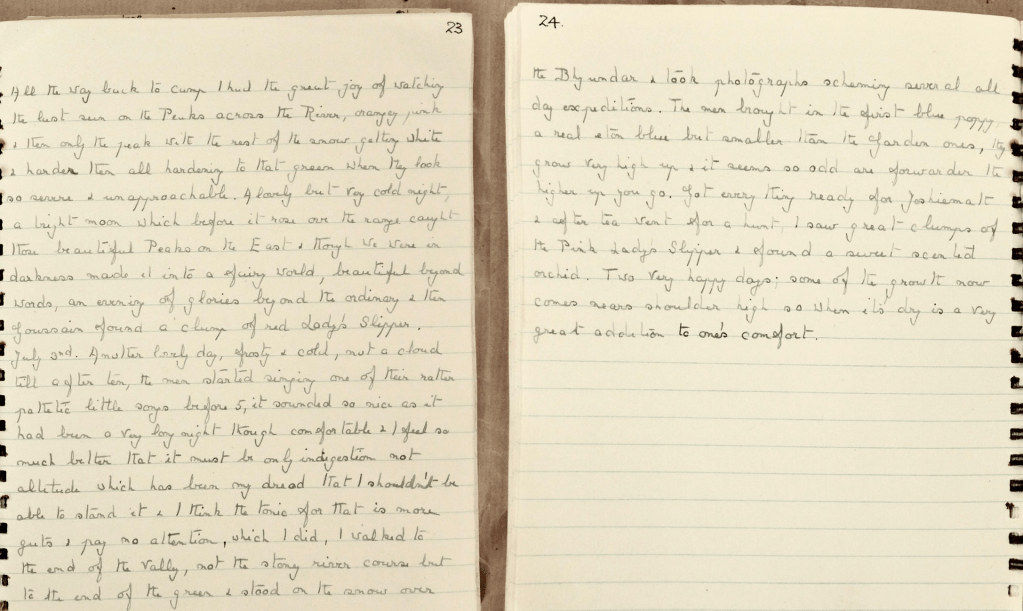

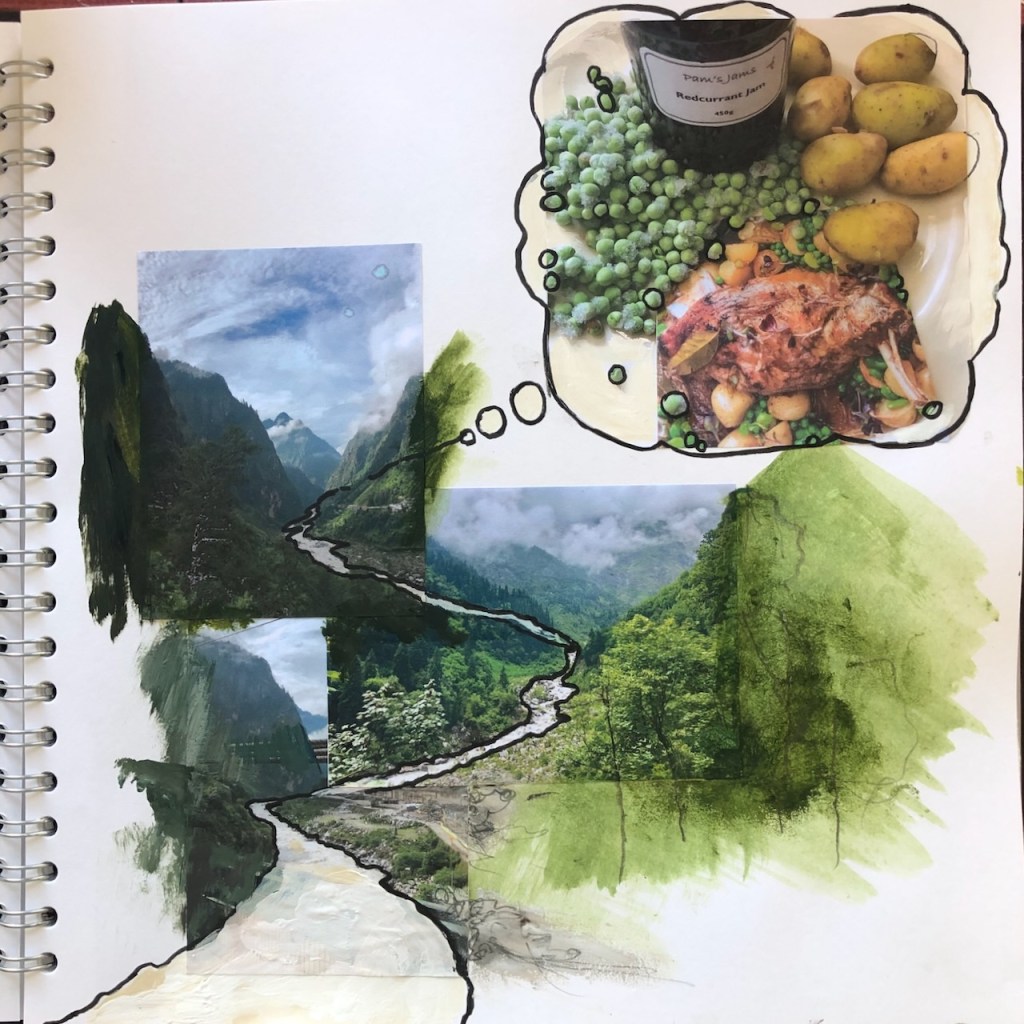

My excitement reading this book was so visceral that this January I travelled to Jena and Weimar to roam the streets they once inhabited. Like them, experiencing a place using all the senses is essential for me to understanding it. Jena didn’t disappoint, despite much of its architecture being destroyed during WWII and later by GDR urban policies. I could almost hear their excited chatter as they crossed the cobbled marketplace, made their way to the Schlegels’ salon, or wandered each other’s minds as they strolled the river in ‘Paradise’. This was Germany at its best – a land of poets and thinkers as well as composers such as Bach, Beethoven and Handel.

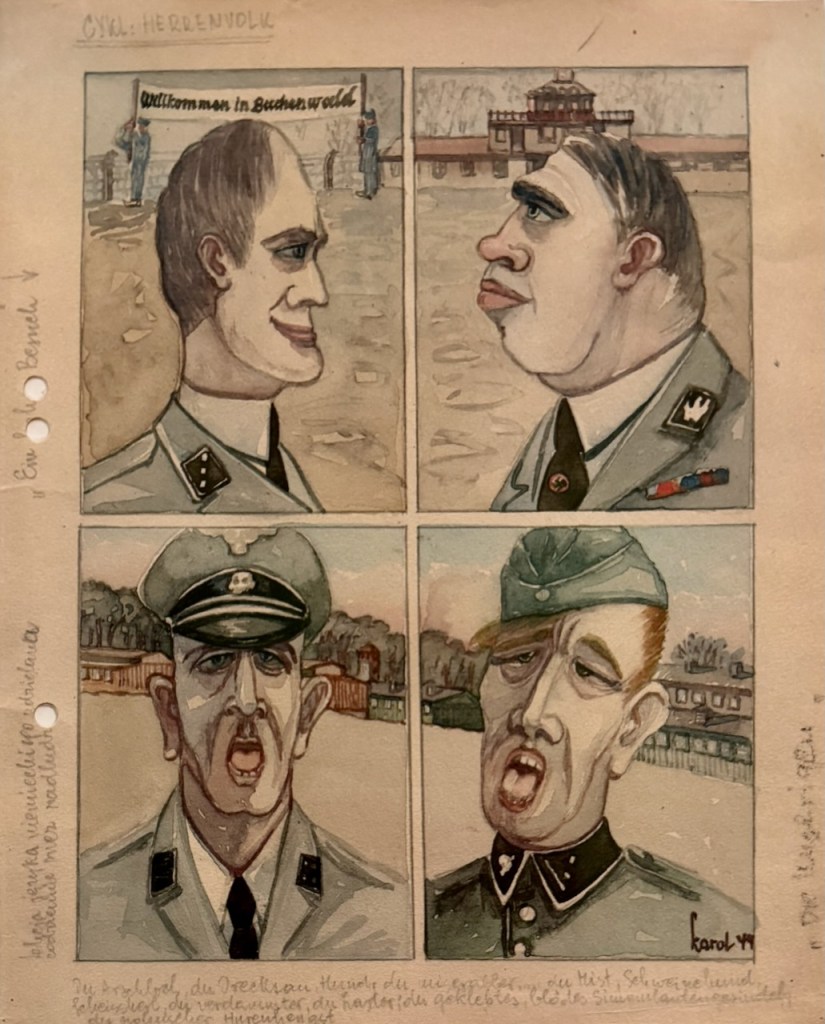

Three days later, I visited Buchenwald, a short bus ride from Goethe’s main home town of Weimar. The former concentration camp stood in stark contrast to the Jena I had just explored. Built in 1937, less than 20 years after architect Walter Gropius founded the Bauhaus in Weimar – a movement that, like the Jena Set, united disciplines, fusing art, craft and architecture into one of the most influential streams in modern design – it imprisoned Jews, political dissidents, Soviet prisoners of war, Roma and Sinti, homosexuals, religious leaders, Polish citizens, women, children, artists and writers… people labelled as wrong, inferior, of no worth.

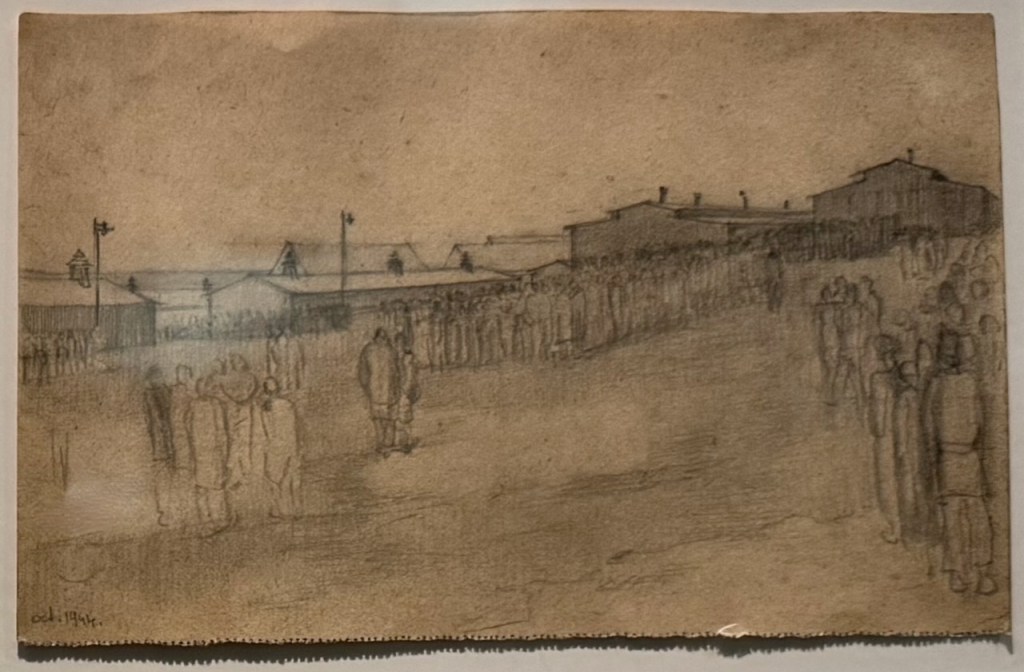

The gates of Buchenwald bear the provocative words JEDEM DAS SEINE (‘To Each His Own’), furtively created in Bauhaus-style lettering by a defiant inmate. Once inside, the visitor instantly shrinks to a moving speck in the vast, seemingly empty arena of former suffering. I clocked the tapping of a distant woodpecker before being swallowed by the site’s app, which conjured visions of hell as I moved from freezing roll calls to the disinfection station, through over-crowded bunks, and into the crematorium ovens.

The theme for Holocaust Memorial Day on 27th January 2026 is ‘Bridging Generations.’ Like my VE Day talks last year – including one with Henry Montgomery (‘Monty’s’ grandson) at the National Army Museum, and more recently with James Holland and Al Murray on their popular WWII podcast We have Ways of Making You Talk – it’s a call to action. As contemporary witnesses die out, the responsibility for remembrance must pass to those who came after.

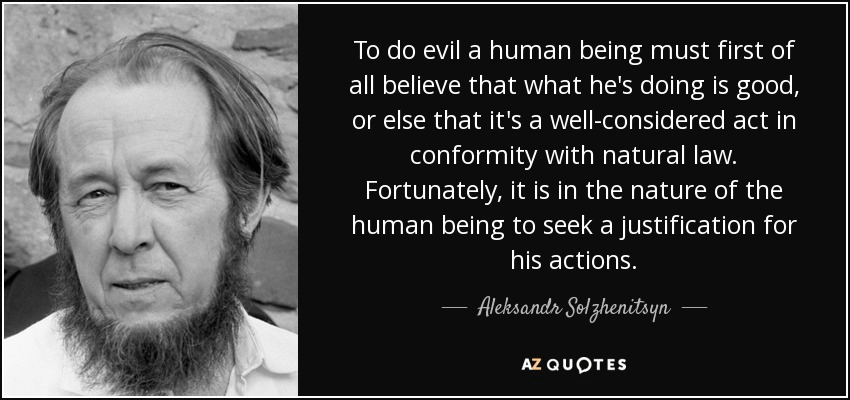

Yet, as a recent Times article highlighted, the number of schools marking the Holocaust has more than halved since the Hamas attacks on Israel on 7th October 2023. This is deeply concerning. It reveals a profound misunderstanding of what the Holocaust warns us about the present. Strip away categories and nationalities, and both perpetrators and victims were first and foremost ordinary people, like you and me.

The contrast between the intellectual vibrancy of Jena and the grim history of Buchenwald mirrors Germany’s descent from soaring heights to depraved depths.

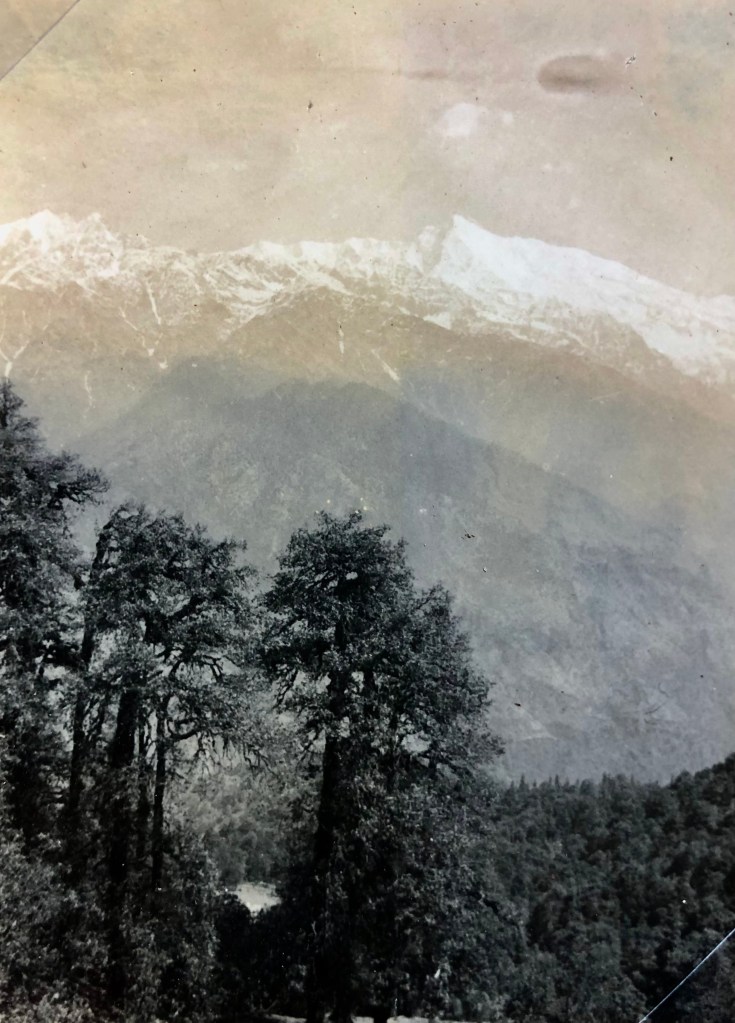

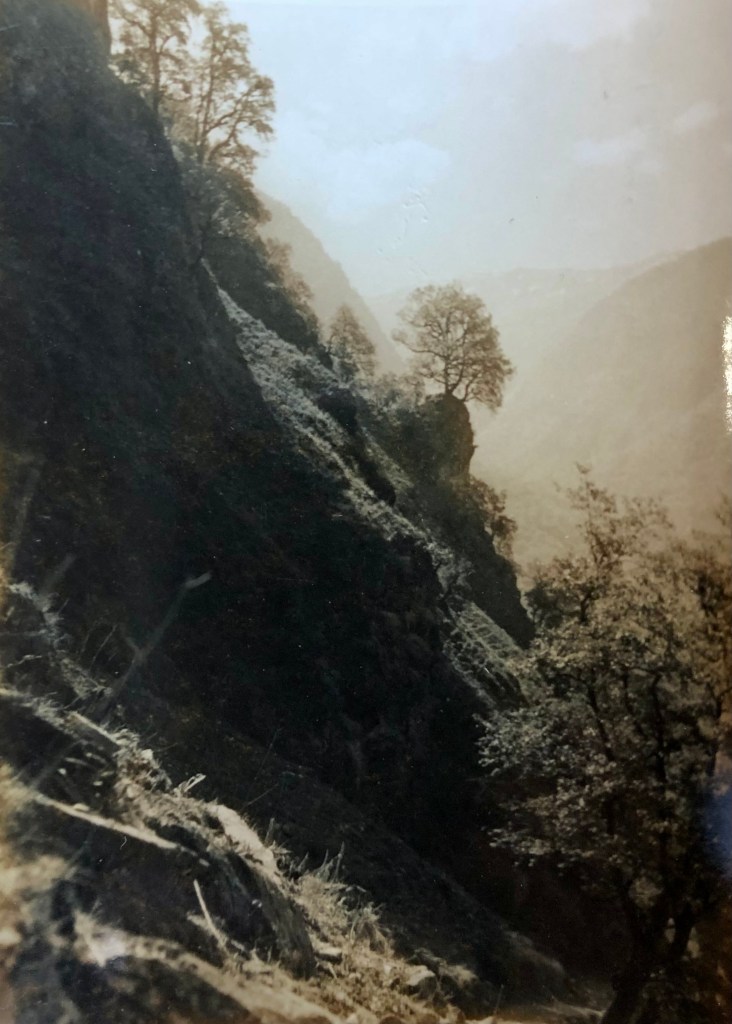

While grieving the death of his beloved fiancée, the Jena Set poet Novalis discovered a new imagery of darkness. He likened his routine descents into the salt mines of Weißenfels to a journey through the wilderness of the self and the universe. He embraced the night as a place of transformation, knowing, as they all did, that light and dark are inseparable.

For me, regular descents into the darkness of prisons or into Germany’s Nazi past have become similar excavations of the human condition. Novalis found a higher existence in the darkness. I found smaller gems. The most important of them all: both the brightest light and the deepest darkness live within us.

Watch or listen to my episode ‘How to commemorate WW2’ on the We Have Ways of Making You Talk podcast