First Encounter with the River Severn

June 1999. You wouldn’t know it was there. Nothing suggests the proximity of Britain’s longest river as you amble down the canal towpath at Frampton-on-Severn. I have a hand-painted sign promising Cream Teas to thank for its discovery. The arrow lured passers-by through a hedge and into a wonderland of round tea tables bedecked with embroidered tablecloths and mis-matching crockery and arranged beneath the boughs of a huge copper beech. A tall man navigated trays of silver teapots and 3-tiered cake stands along narrow paths mown through the long grass.

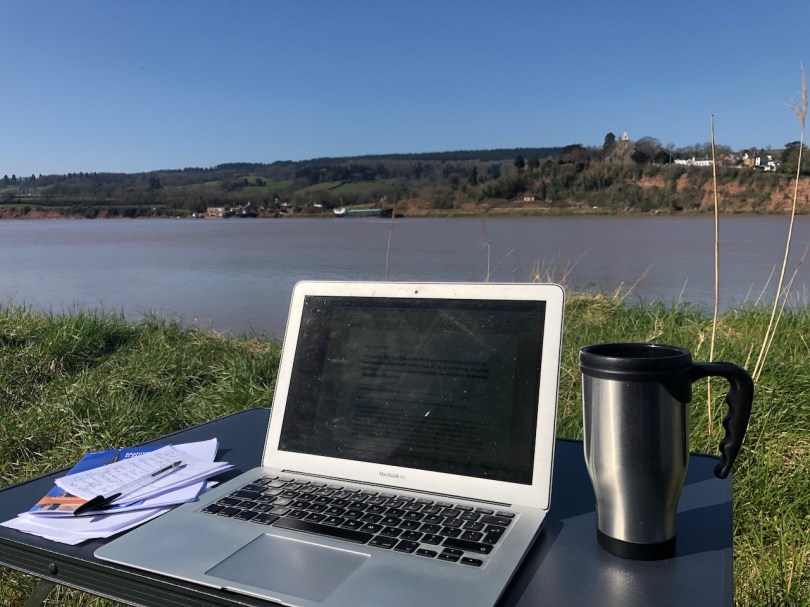

I had moved back to England after 10 years living abroad and was checking out the Stroud area as a possible new home. The top floor of the accompanying Lodge was up for rent, I soon learned… would I like to look at it? A sweeping staircase carried us up two stories and into an apartment of hexagonal rooms adorned with small fireplaces. Then, bending double, two miniature doors awkwardly birthed us onto a roof terrace and into the breath-taking view that would become my world. The River Severn stretched like a taut blue sheet tucked into a distant shore. Low tide mud sparkled. Silence was broken only by the soft chink of teacups on saucers.

Life on the River Severn

I would live in that apartment on the Severn for nearly three years. Every day I walked along the banks of the estuary, my breath aligning with the deep ebb and flow of the tides.

I witnessed the stoicism of a little oak tree holding its precarious own through the seasons, storms and floods; watched cows amble home at dusk accompanied by the swirling black clouds of starlings that condensed and evaporated in the gentle orange glow.

This was where I became a professional artist, scooping rich, melted-chocolate mud into buckets, mixing it with paint and dancing sky and weatherscapes onto large canvases with my hands.

On many a chilly morning I stood on the Severn’s banks with mugs of coffee and expectant crowds waiting for the world’s second highest Bore to swash its way up the estuary and carry brave surfers upstream. Once, in the pitch of night, I crossed its swirling waters in a rickety old boat and returned in the frozen pinks of dawn.

In later years, I would park my camper van on its shores, drink chilled glasses of wine in the sun’s last rays and sleep through rising moons and meteoric showers.

I have a rich store of happy, muddy memories of the River Severn.

Walking the Severn Way from source to sea

For the past eight months I have followed its 220-mile course [albeit not in order] from source to sea; from the peaty uplands of Plynlimon in Mid Wales, north-east through Powys and Shropshire, then south through Worcestershire, Gloucestershire to where it sweeps into the Bristol Channel… the Celtic Sea… the Atlantic Ocean.

Within a mile of its boggy birth, the infant Severn starts tumbling through the Hafren Forest, gathering erratic speed like a toddler until the ‘Severn-break-its-neck’ Falls plunge it into the valley that will bob it to its first town, Llanidloes.

Assuming a steadier gait, it meanders through undulating pastureland before looping north to cross the Welsh/English border at Crew Green. Growing prosperity expands its girth into a watercourse that cuts through floodplains as it heads into the dense cluster of the period buildings and timber-framed mansions that formerly made up one of Britain’s most prosperous wool and cloth trade towns, Shrewsbury.

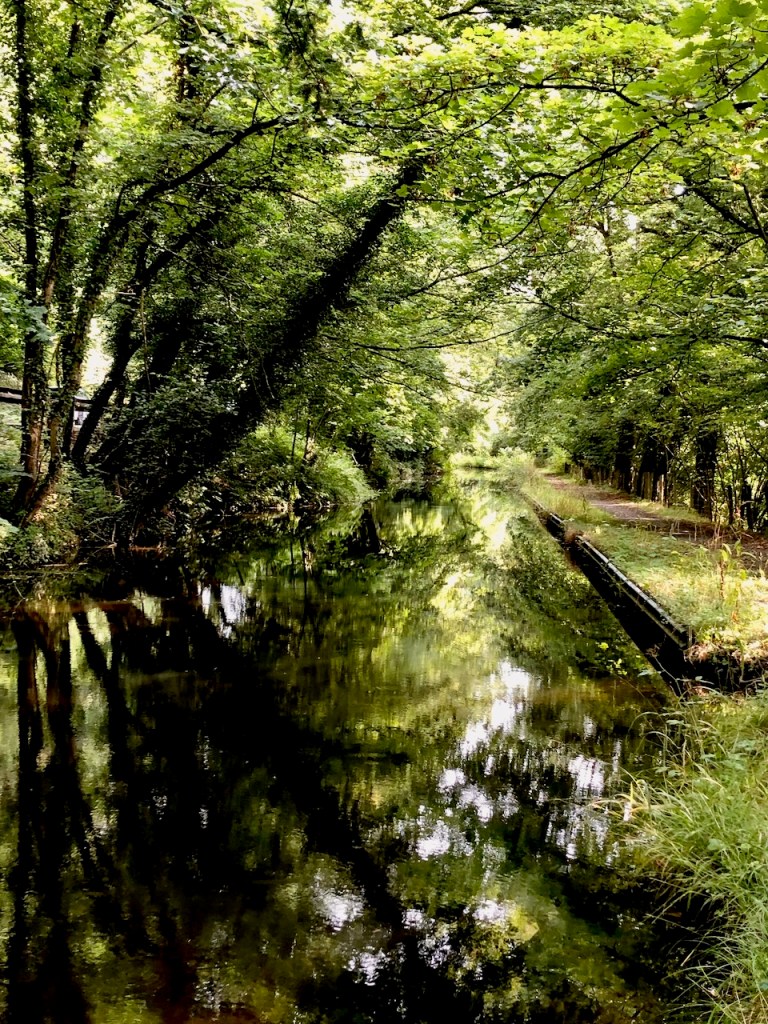

Past the birthplace of Charles Darwin, a glassy stillness and almost imperceivable flow belie the Severn’s true force as it smoothly snakes its path between overgrown banks of willow, elder and the deceptively pretty pinks of thuggish Himalayan Balsam.

History punctuates the landscape with traces of Roman forts and roads, a Saxon chapel, the evocative ruins of the Cistercian Abbey at Buildwas, 16th Century market halls and sandstone caves that once sheltered hermits or stranded travellers unable to cross the river. As the Severn bullies its way south through gorges striped by coal, limestone and iron ore strata, the legacies of once booming industries and trades are memorialised in mines, railway stations and canals that once linked local towns across Britain.

Regular bridges drip feed the imagination with the industrial revolution. Ironbridge boasts the world’s first iron bridge cast by the grandson of Abraham Darby in 1779 in the wake of his grandfather’s revolutionary discovery seventy years earlier that coke could be used for smelting iron instead of charcoal. Further downstream, the fortified town of Bridgnorth perches on a sandstone cliff. Once the busiest port in Europe, it hummed with the sound of iron works and carpet mills, breweries and tanners until the 1860s when railways heralded the end of river trades.

Following its increasingly wide, milky-coffee-coloured road, vocabulary from school geography lessons surfaced from the recesses of my turbulent education: Oxbow lakes, flood and sandbanks, confluences; soaring cumulonimbus or, equally frequently, water-dumping nimbostratus clouds.

South of Gloucester and around the peninsular at Arlingham, the now tidal Severn breathes in the sea and releases the river out into the vast estuary. At Purton, the ghostly remains of a graveyard of more than 80 sunken barges reveal man’s hopeless struggle to halt the erosion of the banks. Through the working docks at Sharpness and past a pair of looming power stations, the two Severn Bridges rise like misty goalposts. Portals to the open sea. And an abrupt, somewhat unspectacular end to the Way.

With the walking completed, there remained just one more aspiration: to surf the Severn Bore. A bad dream thankfully warned this novice surfer with a fear of water off. Instead, I rode the Bore in a boat driven by its champion.

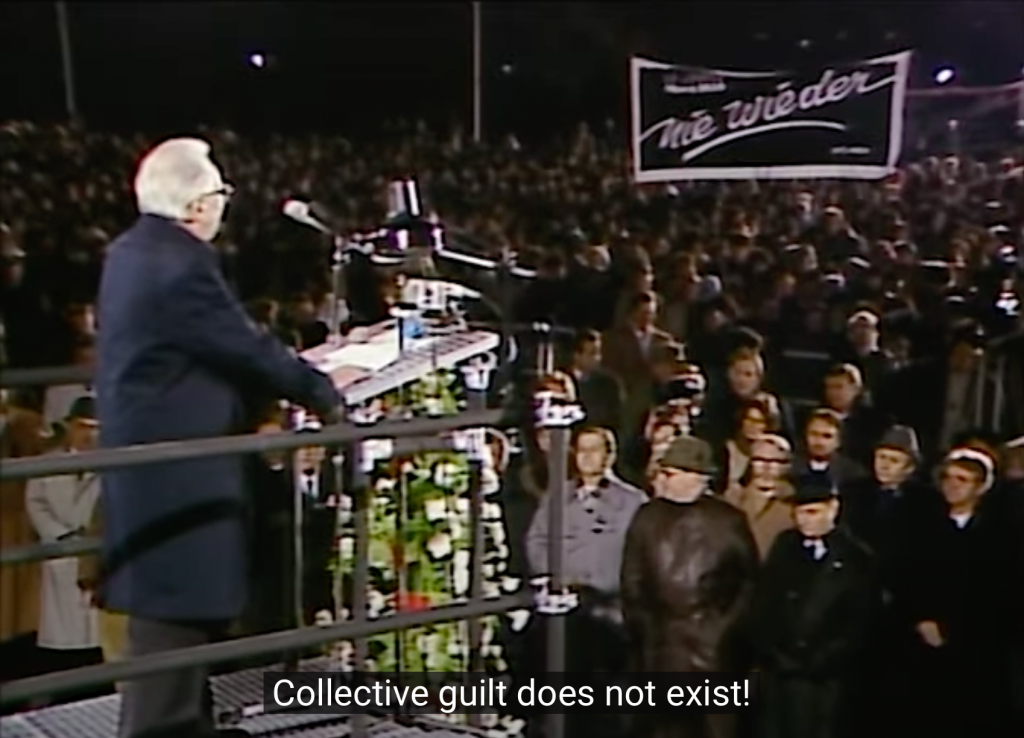

We set out on a slack tide in the early dawn, deposited two surfers into the tidal stream and waited. You can hear the roar as it approaches. Pulled by the force of the moon, a small line of foam scrabbling its way against the flow comes into view, gathering body until it is a swell. And then you are on it. Riding the crest as salty water from far away thrusts its way up the river dragging the sea in its wake like a heavy cloak.

Immersed in the perfect balance of the 4 elements, the smile on my face remains for many hours. The magic of Sabrina will last a lot longer.