“Sometimes in moral philosophy it’s important to think about plants.” I heard these words in last week’s In Our Time and they chimed with my current shift of focus from war to flowers. They were said by the leading philosopher, Philippa Foot, to a room full of Oxford males. She was basically saying that moral evaluation should be see as a continuum of the way in which we see other living things.

A week earlier, I was sent a link to a video by Yanis Varoufakis, former finance minister of Greece, whose proposed speech in April at the Palestine Congress in Berlin was stormed by police and banned. [You can have a listen to his reconstruction of it here.] Somehow I found the two were connected.

So what is happening in Germany in relation to Israel’s war on Gaza? Some reports are pretty concerning. It is understandable that Israel’s security and right to exist has long been Germany’s ‘Staatsräson’ (reason of state). However, since the Hamas-instigated horrors of October 7th, the belief in Israel’s right to defend itself has evolved into a fairly uncompromising pro-Israel position that seems to equate any criticism of Benjamin Netanyahu’s policies with anti-Semitism. Friends in Germany relate how alarmed people are by the shutting down of debate and silencing of different voices, both painfully reminiscent of the authoritarianism and loss of democracy of Nazi Germany.

The German government’s unswayable support of Israel in whatever it does is a result of Germany’s past. It is seen as morally the right thing to do. But could nearly eighty years of the world’s media placing Germany and Guilt in the same sentence to explain everything, from its open-arm policy towards refugees to its hesitancy to supply weapons for use against Russia, now be backfiring?

My German mother will be 90 this weekend. She was 11 years old when the Second World War ended and is one of increasingly few Germans who experienced Nazism first hand.

In the post-war decades, collective guilt and accusations of complicity in the Nazi atrocities were attributed to the entire German population. Plenty of people consider subsequent generations guilty too, by way of blood / nationality / family association. You might remember my 2018 blog ‘Shot for what you represent’ with the incident of the English woman who, on hearing I was half-German, picked up her hand off the table, turned her fingers into a gun and shot me in the face! In her eyes, all Germans are unquestionably guilty and “jolly well should feel guilty” too.

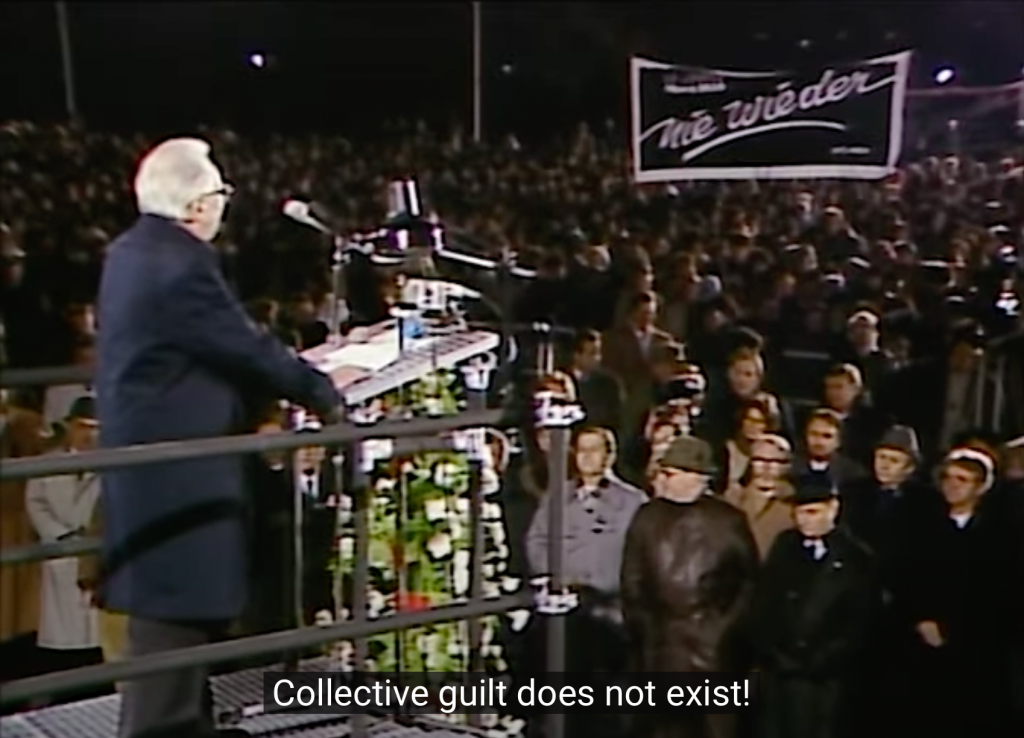

This is in stark contrast to many Holocaust survivors such as Sabina Wolanski, who said at the inauguration of Berlin’s Holocaust Memorial in 2005: I do not believe in collective guilt. The children of the killers are not killers. We must never blame them for what the elders did, but we can hold them responsible for what they do with the memory of their elders’ crime. Similarly Viktor Frankl, author of the seminal book “Man’s Search for Meaning”, who in a 1988 speech spoke out against the very concept of ‘collective guilt’ describing it as a continuation of Nazi-ideology.

I believe they are right. I understand how Germans, myself included, might feel shame for being part of a group who allowed genocide to happen. Many also feel a deep sense of responsibility for not allowing it to be forgotten and making sure it doesn’t happen again. But guilt?

Let’s explore the dynamics of this word for a moment.

Guilt is the result of an action within our control and responsibility. To be guilty, you have to have done (or failed to do) something that falls out of the framework of what is socially acceptable by the group with consequences of harm to an ‘other’. Frequently ‘guilty’ parties will not feel guilt or shame as they see their actions as having been justified, necessary, righteous even, within the context in which they were committed. Resentment and retaliation for being deemed ‘guilty’ can follow.

In Who’s to Blame? Collective Guilt on Trial, Coline Covington describes how Judeo-Christian cultures place particular emphasis on guilt, forgiveness and atonement alongside rituals that are supposed to restore moral order, cleanse the groups of shame and hatred, and prevent or close cycles of vengeance. For a long time, I have believed this was right and Germany’s culture of Vergangenheitsaufarbeitung (working through the past) and counter memorials was an example to all of us of how things could (and should?) be done. I am no longer sure that is what’s needed now.

The problem is, Covington says, that most restorative rituals for peace-building are built on a binary understanding of good and evil, right and wrong, victims and offenders. “The finger of blame is pointed and yet true healing is meant to eradicate blame. This inherent contradiction contains the seeds of failure.” Could it be that we are witnessing this failure in Germany, Israel/Gaza, Russia/ Ukraine and elsewhere, resulting in new perpetrators and victims of atrocity and trauma?

If so, how do we overcome binaries? I tried a couple of weeks ago in an online group of Jews, non-Jewish Germans, my own Anglo-German mix and others. Someone had been talking about the frightening increase in anti-Semitic acts and some members of the group had dismissed those behind them as ‘idiots’. A common reaction to unacceptable behaviour, and I have said the same many times in relation to certain members of the Tory party! But it got me thinking… because when we proclaim a shocked judgment: “How could they!” How stupid!” “How awful / evil / weak!”, we are basically believing: If I were them, I wouldn’t do what they are doing. We are seeing ourselves as morally superior, stronger, more intelligent and right, while ‘they’ are inferior, guilty, ignorant, wrong.

Does this dynamic not replicate, in an initially small but precise way, the dynamics behind the Nazi, or indeed any, discriminations and judgments against apparent ‘lesser mortals’?

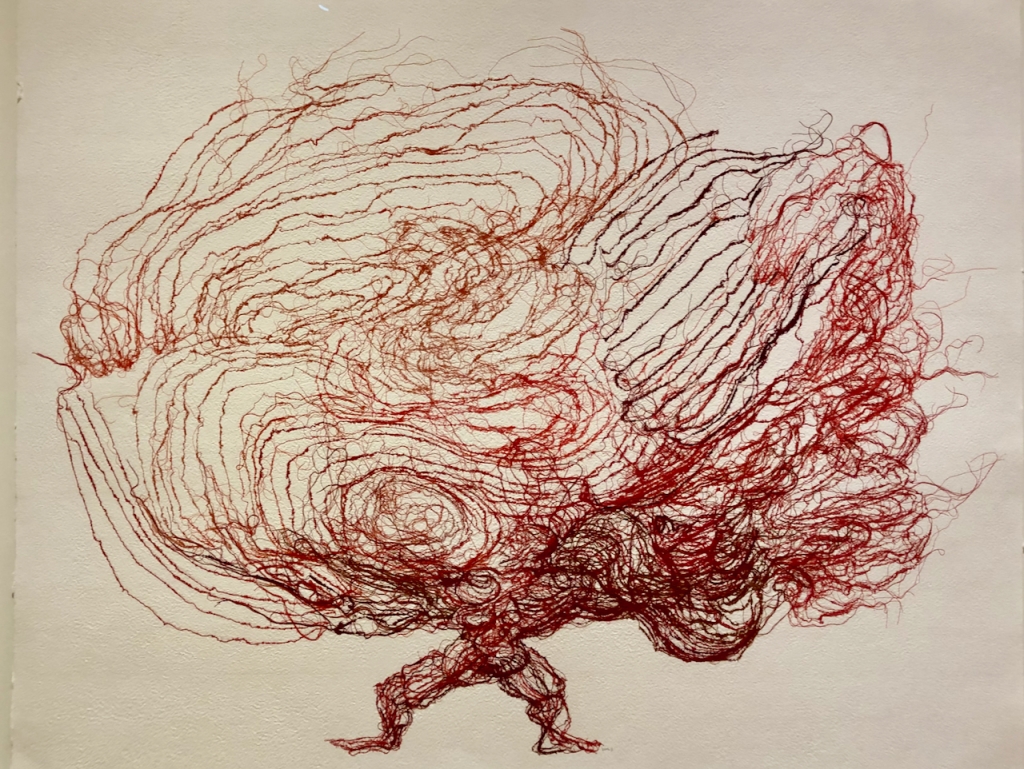

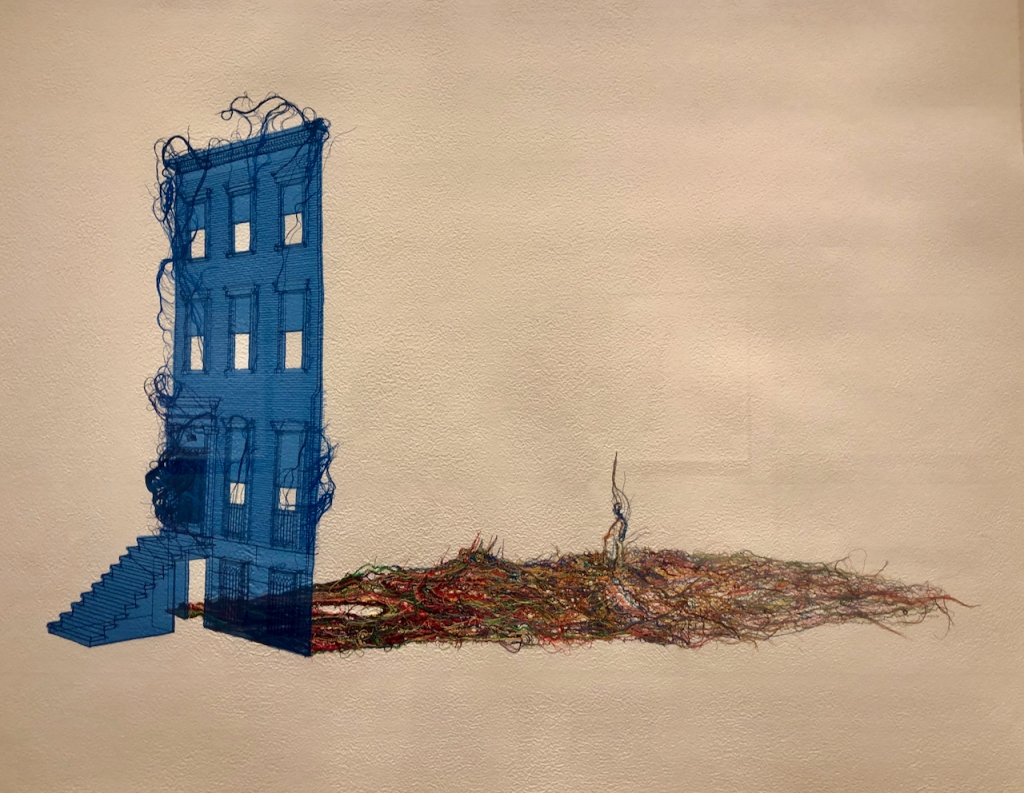

In this particular constellation, I naturally belonged in the ‘German perpetrator’ rather than the ‘Jewish victim’ category. It’s an uncomfortable place to be, but I have noticed that since finishing my book, the label no longer sticks as well. My grandfather’s shadow that once draped over my identity like a huge cloak has been so comprehensively unpicked, understood, transformed and woven into the fabric of my whole being that I can no longer see people in such binary terms. Like the beautiful art of the Korean artist, Do Ho Suh, whose exhibition Tracing Time I saw on a recent trip to Edinburgh, I can see how we are all threaded together into a colourful tangle of humanity, each one necessary and part of the whole.

There were people in the group who suggested I was ‘absolving’ myself and wanting to free myself of the burden of guilt, almost as if this was utterly impossible or prohibited. I do understand that response and how for descendants of survivors, this could feel an affront. But, without diminishing any of the suffering of and compassion for the descendants of survivors, I myself choose to no longer see people in terms of “my side/your side”, as one member put it. I believe that in order to overcome the judgmental binaries of ‘us-good’ and ‘them-bad’, we all need to make a greater effort to understand what lies behind bad or evil deeds. We not only need to step into the other person’s shoes, but into their entire situation. Only then can we recognise that if we were in the totality of their internal and external life, we would act, or would have acted in exactly the same way as them. The results of Milgram’s 1961 experiment with obedience to authority suggested something similar. Apparently good people, like us, can also become capable of extreme bad.

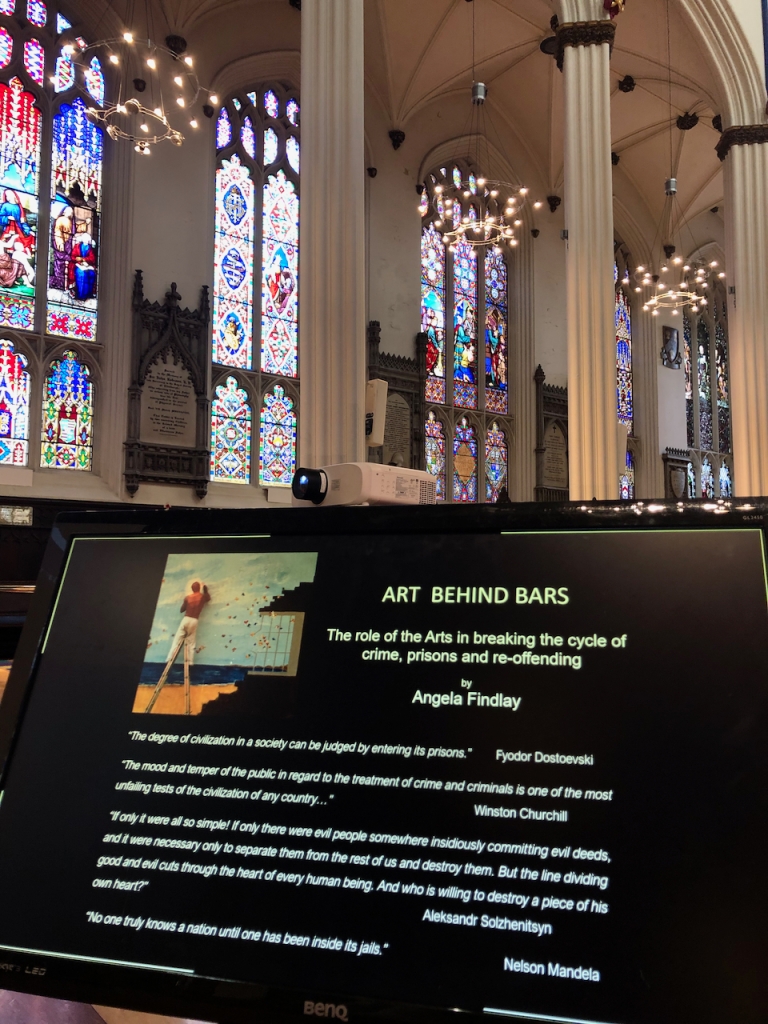

You will all I am sure now know about the horrendous, inhumane conditions of HMP Wandsworth and so many of Britain’s jails, and the decades of glaring failures of our Criminal Justice System in general. (If not, you can get an impression here and here and here) None of us live very far away from a jail, and yet so many of my Art Behind Bars talk audiences say they had “no idea.” Will we too one day be judged and found guilty of the stigmatisation of offenders that enables this shamefully degrading system to exist in our name as a fulfillment of our wish for governments to be ‘tough on crime’? Will we be accused of turning a blind eye, not acting and later claiming ‘we didn’t know’?

I am deliberately being a little provocative to make a point. Because as far as I can see, the only way we have a chance of breaking the catastrophic cycles of blaming and shaming, violence, retribution – all outcomes of seeing each other as ‘other’, separate and different from ourselves – is to create a level playing field of mutual respect where both (or all) sides are treated equally. And it can start within each one of us. In everyday situations. Now.

This is the African concept of ‘Ubuntu’, a philosophy of interconnectedness, sometimes translated as ‘humanity towards others’ or ‘I am because we are’. The most recent definition provided by the African Journal of Social Work (AJSW) describes Ubuntu as: A collection of values and practices that people of Africa or of African origin view as making people authentic human beings. While the nuances of these values and practices vary across different ethnic groups, they all point to one thing – an authentic individual human being is part of a larger and more significant relational, communal, societal, environmental and spiritual world.

According to Charles Eisenstein, author of The More Beautiful World Our Hearts Know is Possible, aligning ourselves with the truth that ‘if I were in the totality of your circumstances, I wouldn’t do differently from you,’ and the compassion that arises from putting ourselves in another’s shoes and seeing us as one, is “perhaps the most powerful way to magnify our effectiveness as agents of change.” I think I agree.

Further Reading / Listening (as always, not necessarily my opinion)

What’s behind Germany’s support of Israel? – Inside Story Podcast, 10th April 2024

As war in Gaza rages, what’s behind Germany’s support of Israel? – Al Jazeera

Historical Reckoning gone haywire – Susan Neiman, The New York Review

Germany’s crackdown on criticism of Israel betrays European values – Al Jazeera

Germany’s historical guilt haunts opponents of Israeli war in Gaza – France 24

A Clean Break by Tom Holland – A Point of View, BBC Radio 4

wowza Anglea, much to reflect and to spend time on considering

Thank you

thank you too Sarah for engaging with it.

Thank you Angela. Very good piece. I don’t think inherited guilt is at all helpful – especially if the consequences end up having a perverse effect – such as in Germany’s unconditional support for Israel – regardless of its actions. We cannot be responsible for the actions of our predecessors, but it’s probably important to be aware and take steps to prevent catastrophe in the future. Possibly the best way by supporting the democratic process, rule of law, freedom of speech etc.

I think you’re right to state that it’s not helpful to take a binary approach towards judging people. In the right (or wrong) circumstances most people are capable of egregious behaviour, including and up to murder. The best protection we have is the institutions of a democratic state – including parliament, independent judiciary, free-press, schools, universities, police, health service etc etc. The Nazis knew this and hence the vast majority of Jews and other victims were murdered where the Nazis had previously destroyed the state, mainly in Poland and Western Ukraine. Without a state there was no law, no institutions etc to protect people. The majority of victims were shot and not just by the SS. Many were ordinary soldiers and German police officers, together with the militia and police from other countries where the state had been destroyed, either by the Nazis or Soviet Union. I think in many ways the Nazis, SS, Gestapo and Auschwitz have been a simple and convent way of explaining the Holocaust: reinforcing your points about binary judgments etc. The truth is much more complex and says a lot about both human nature and what we need to do to constrain the worst elements.

The current UK Government’s Rwanda policy and threats to leave the ECHR are I think a classic demonstration of trying to break away from the rule of law in order to act in an inhume way towards others.

Having said the above I think we must also be cognisant of individual human agency: it matters. Trump is a good example. Ultimately it was the democratic institutions in the US that constrained him. We may not be so lucky next time!

For further reading on the Holocaust and in particular the Nazis policy of state destruction in order to carry out mass murder, I recommended Timothy Snyder’s ‘Bloodlands’ and ‘Black Earth’. Professor Snyder has spent his life studying Eastern Europe and in particular the Holocaust.

Finally, I think we can have too much history, too much remembering. I like the historian Timothy Garton Ash’s view: “To function well, we do have to forget a lot.” I think he has a point.

Best wishes

Mick

Thank you for such a thought-provoking response, Mick, a blog in itself offering so much to think about.

I agree the framework and tools of the state are essential. And then maybe it’s once again that dance between our inner and outer worlds. The actual decisions on how to behave come from within. So many testimonies of people who have behaved in remarkable ways in horrendous situations show how tiny choices and decisions lay behind their attitudes to not replicate the harm being done to them and those around them. And that in turn causes a tiny break in the destruction.

I also agree we can do too much remembering, and one-sided memory of a chosen trauma and/or glory for political means, as many nations employ, is a big part in perpetuating the cycles of revenge and violence.

It’s always good to hear your informed and thoughtful point of view, thank you.