Happy Spring Equinox! I am writing this on the banks of the River Severn, one of my favourite spots in the world. The sun is shining in a cloudless sky, a breeze is dancing through the long grass. I can hear the outgoing tide making its way back to the sea. Within this natural order and peace, it is almost impossible to imagine the horrors of war.

Like all of us who are far from the fighting front, I feel the combined rage, helplessness and deep sadness of seeing and hearing the heart-breaking scenes and accounts of the millions of Ukrainians fleeing their homes or defending their country, their freedom and their lives. Words seem to be my only weapon against this appalling aggression. But what words would help? And which ones won’t? There is such a fine line between the impactful bravery of calling something out, of revealing the truth in the face of lies, like the Russian TV employee who ran onto the set of Russia’s main news channel bearing a placard saying ‘Don’t believe the propaganda, they’re lying to you here’ while shouting ‘Stop the war. No to war,’ and the potentially catastrophic naming, shaming and blaming of an individual.

I know that I want to use my words to help bring about peace. Which is why I choose not to use those that I feel add both to the divisiveness that lies behind all wars and to the ‘othering’ of the enemy, which in turn nurtures the erroneous belief that violence and force are the only ways to achieve aims and justify actions. It’s also why listening to Radio Four’s Woman’s Hour on Thursday 17th March left me unsettled.

I am not usually one to come down on the side of politicians’ typically evasive methods of answering a question. But in this case, I was behind the Foreign Secretary, Liz Truss, in her response to presenter Emma Barnett’s questioning. It went something like this:

Barnett: ‘Is Vladimir Putin a war criminal Foreign Secretary?’

Truss: ‘I think there’s very, very strong evidence that war crimes have been committed in Ukraine and that he is instrumental to those war crimes taking place.’

Barnett: ‘Is that a yes?’

Then, citing USA’s President Biden’s recent declaration that ‘he is a war criminal,’ she continued to push Truss. ‘Why don’t you want to cross that line? That line has been crossed by America and I am wondering why we’re not.’

Truss then repeated her noncommittal answer.

And I was glad she did. I didn’t think that style of political grilling was appropriate here.

Some might see Truss’s line as weak. Maybe you do too? I actually don’t. For what, other than an escalation of diplomatic tensions and danger, is to be gained by shoving Putin into the ‘war criminal’ category, even if he is one? By branding him with what is potentially the worst label there is, do we not put him on the defensive rather than encourage constructive conversation? Hitler was a war criminal. And Putin is a million miles away from allowing himself to be equated with him.

A Kremlin representative’s inevitable response was to call out Biden’s statement as ‘unacceptable and unforgivable rhetoric on the part of the head of state whose bombs have killed hundreds of thousands of people around the world.’ Of course we all know he has a point when you look back at certain episodes of American history. And that is my point. Such statements do nothing other than to add fuel to an already raging fire.

None of this is to say I don’t abhor what Putin is doing as much as anybody. I am just aware that words are absolutely crucial in the dealing with a person whose psychological makeup is so volatile, so proud, so convinced, so terrifyingly dangerous. Because while our acts may be indisputably heinous, we human beings, in all our complexity and contradictions, are never just one thing. So to stick a supremely negative label onto someone – even if they have qualified for it a thousand times over – is in my view counter-productive, especially when, however mad it seems to us, they see themselves in a very different, invariably more heroic light.

While working in prisons, I saw the negative dynamics of labelling people ‘murderer,’ ‘terrorist,’ ‘child abuser’ – even when they were guilty of these crimes. Like the locked door of their tiny cells, there was no way out of that ‘bad’ box. Impotent, ostracised and with no obvious path leading back into the world of ‘good,’ many gave up trying. Some killed themselves. Some continued to numb the shame and sense of separation with drugs or self-harm. Others turned to violence in a futile attempt to punch their way back to the acceptability and respect that ironically often lay behind the motivation to commit their original crime. Shame has a hideous way of making people infinitely more dangerous.

We only have to look at the Germany of the 1920s, 30s and 40s to see what grew out of the humiliation of the Versailles Treaty and above all the ‘war guilt’ clause, which forced Germany to accept all blame for World War One. Or to be reminded, as I was on a recent trip to Hamburg and the blackened ruins of the St. Nicholai church that had so fascinated me as a child, that every nation and each of us are capable of descending into horrific violence, even potential war crimes.

If we are to believe that conflicts begin in the hearts and minds of individuals, then it follows that peace does too. Of course I don’t know for sure, but my feeling, at least from a psychological point of view, is that at this incredibly precarious and dangerous moment in time where the course of the war in Ukraine could escalate in so many directions, we should be doing everything to enable Putin to withdraw, retreat or feel sufficiently victorious to end his war with at least a perception that enough of his dignity and integrity are intact.

I totally understand both the temptation and justification of condemning Putin and his actions as outright evil. But the stakes are currently too high to play the ‘we’re right, you’re wrong’ game. For to do so is to accuse and other the perpetrator in the same way they have accused and othered their foe. Like negotiators communicating with hostage-takers, albeit on an infinitely larger scale, maybe we need to keep in our view the man behind the monster. As many in the west are now admitting, this is possibly what we have neglected to do in the past. And he who feels unheard, unseen, disrespected often feels impelled to stamp louder, punch harder to get themselves noticed.

I think our personal choice of words is one of few things that each of us have as a tool to diffuse rather than escalate a situation. I just hope we can all find the right ones.

On another note, exactly this time last year, I was giving my Tedx talk. You can watch it here… again or for the first time if you haven’t seen it already.

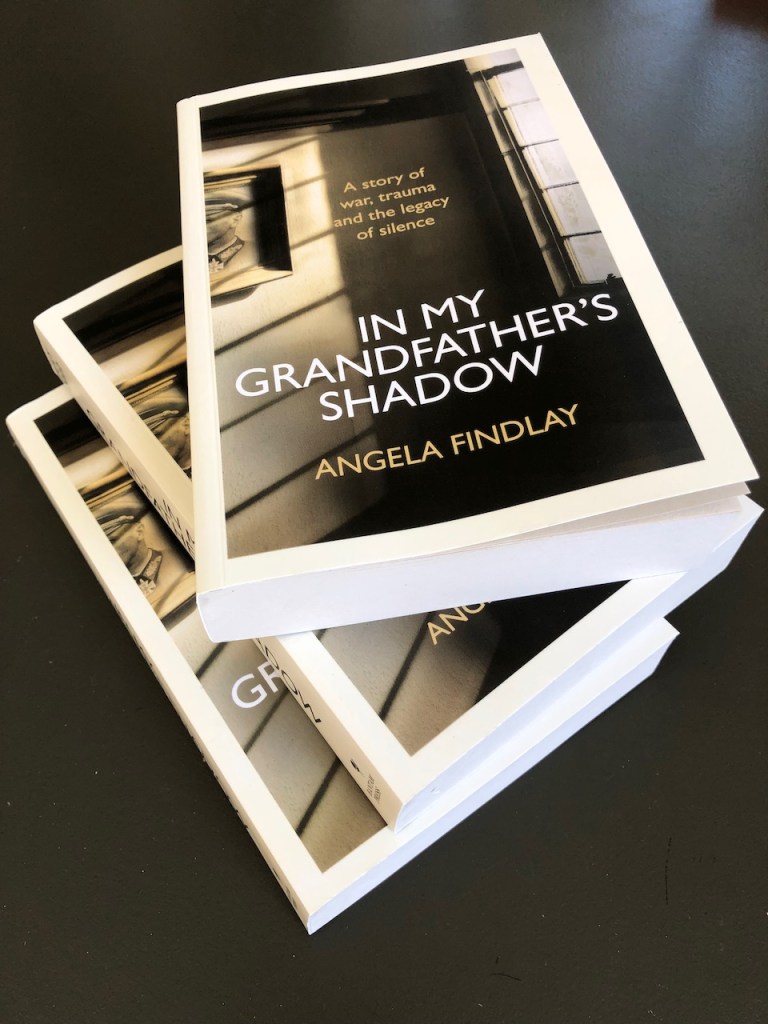

And yesterday I received the printed proofs of my book In My Grandfather’s Shadow. Still not the final product, but another exciting step towards publication in July. You can pre-order on Amazon here or wait until July to buy in a bookshop.

Related Links

Woman’s Hour Interview with Liz Truss – start at 13.30 mins

Hi Angela, I don’t always agree with your position on some of the articles you write , unbelievable I know 😉.

But have to agree with you here , some of the journalism on such an apauling and volatile situation isn’t always in my mind, constructive.

As ex military, and someone that has had personal experience of the previous cold war. I am by no means an apeaser, far from it, but sometimes you can talk up a situation, that pushes someone into an action that was not enevertible.

Sepeately , Looking forward to reading your book , been wondering how it was coming on.

Thourghts and best wishes to you and All those affected by the war on Ukraine.

Thanks Kevin. Good to hear from you and thank you for reading. I am glad you both disagree and agree with my posts! I find that much more interesting than talking in an echo chamber. Look forward to catching up one day and best wishes in the meantime.

Thank you for ever-interesting observations. The contrast with Ukraine and Hamburg (where I am off to next week for the first time) is very thought-provoking. I agree about not prodding the Putin further, and the importance of a measured stance (above all, from those in pubic office). I keep on thinking of ‘Bloodlands’ by Timothy Snyder, and try to understand why this part of the world has been subjected to so much tragedy for the past century.

Thank you too for your comment. And I hope you have a good time in the wonderful Hamburg. It does indeed seem like some places suffer relentless tragedy and others don’t

THANKYOU Angela for these thought provoking words. The paragraph on shame and your reference to the negative labelling resonated. I feel this is a real problem not only with those in prison but with any who make a mistake or struggle with mental health. I ve seen this first hand white a young man who will probably never come back out of his box of shame and blame. It’s tragic

As is the war and the ongoing negativity tirades that are banded around

Thanks for sharing and writing so eloquently

I will be buying your book directly from the bookshop

I can’t wait to read it. Congratulations!

Sarah

Thank you Sarah, I know you know this area well first-hand and have much wisdom to bring to it and others.