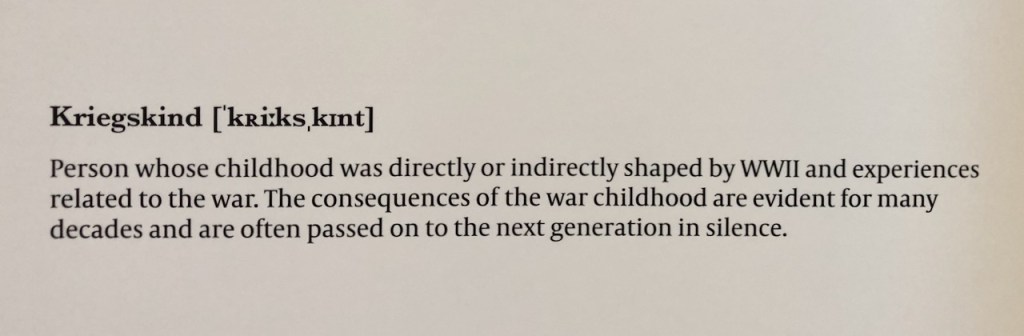

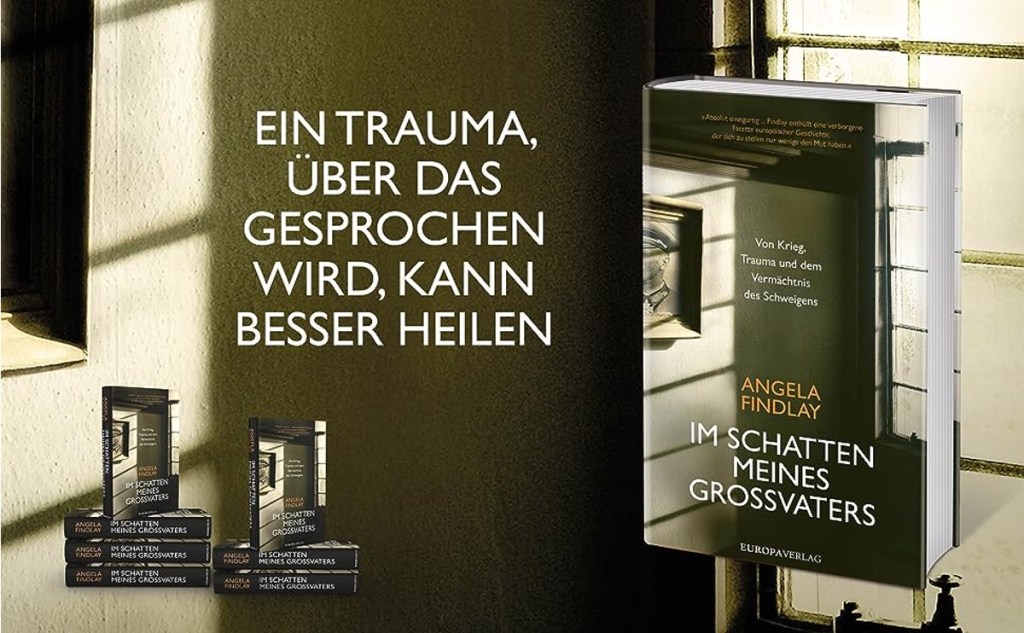

There was something profound about launching the German translation of my book in Germany, first in Hamburg, the city I have known and loved all my life, and then in Berlin, the epicentre of that extraordinary episode of history in which I have been immersed for over 15 years.

I had no idea what reception it or I would receive. The audience have, after all, breathed the air of Germany’s past for decades; been shaped by it – whether they have engaged with it or not. German 20th century history is still very much alive in the present, a minefield of sensibilities and taboos through which I had to pick my way, all too aware that as a half-Brit, I always had an airlift out of the horrors. What on earth could I bring to the intensely discussed narratives?

So I was touched by how warmly I was received. How attentively people listened. How sincerely they responded, one elderly man, born in the same year as my 89-year old mother, standing up and telling the story of his childhood flight from the Soviets for the first time. The entry level of questions was so deep, so knowing, so very real.

As always, it was the post-talk discussions, with much needed glasses of wine in hand, that brought home to me once again the importance of talking about what is all too often buried. People expressed how completely new it was for them to hear someone talk so openly both about German soldiers and themselves. This is deliberate on my part. By baring the inner machinations of my soul and that of my grandfather, I was and am inviting people to explore theirs. By touching on taboos, exposing shame to the light of empathy and sharing the tools I developed and steps I took to release myself from the crippling weight of Germany’s Nazi legacy, I can offer hope that there is a way through. Through, not out of. For such an unprecedented past must necessarily maintain the weight of responsibility.

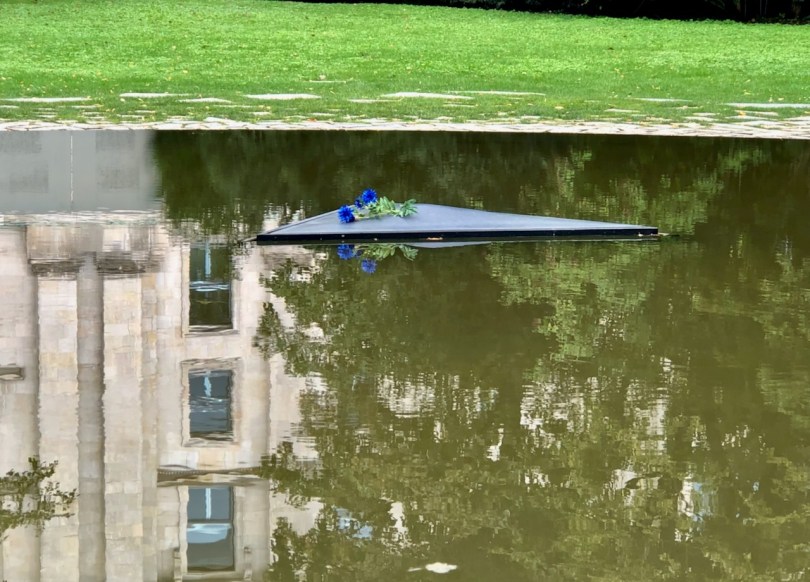

As a nation, Germany continues to respond to its crimes in countless ways, not least through its counter memorial culture about which some of you may have heard me speak in my lectures. One memorial in particular chokes me up every time. It is the Memorial to the Sinti and Roma of Europe murdered under National Socialism placed right in the heart of the city between the Reichstag and Brandenburg Gates. (I mentioned it in my June BLOG on Berlin)

The central feature is a circular pond with a triangular ‘island’ on which a fresh flower is placed every day. That some official is tasked with performing this ritual intrigues me. So, after receiving permission to witness it, I joined a delightful man in uniform by the water’s edge and duly followed him into the bushes. Hidden from public view, he pulled opened a grated trap door and gestured to me to descend the precarious metal ladder and proceed along a damp corridor until I was standing directly below the retractable triangle. At 1pm precisely he pressed a button. An accordion-like black triangular pillar began to lower, folding into itself until the flower was within reach.

I was then allowed to select and place a new flower on the triangle – a slight disappointment that for practical reasons, the flowers are no longer fresh but plastic! Then, with another push of the button, up it went to take its place in the still water for another day.

As we emerged from the bushes, a school class of pupils who had been brought to watch the ceremony approached us. The teacher had noticed me disappearing into the undergrowth and asked if I would explain who I was, what, why…etc. which I did. And, long story short, from that encounter and the interest it generated, I received an invitation to come to their school next time I am in Berlin and tell them about my story and my book!

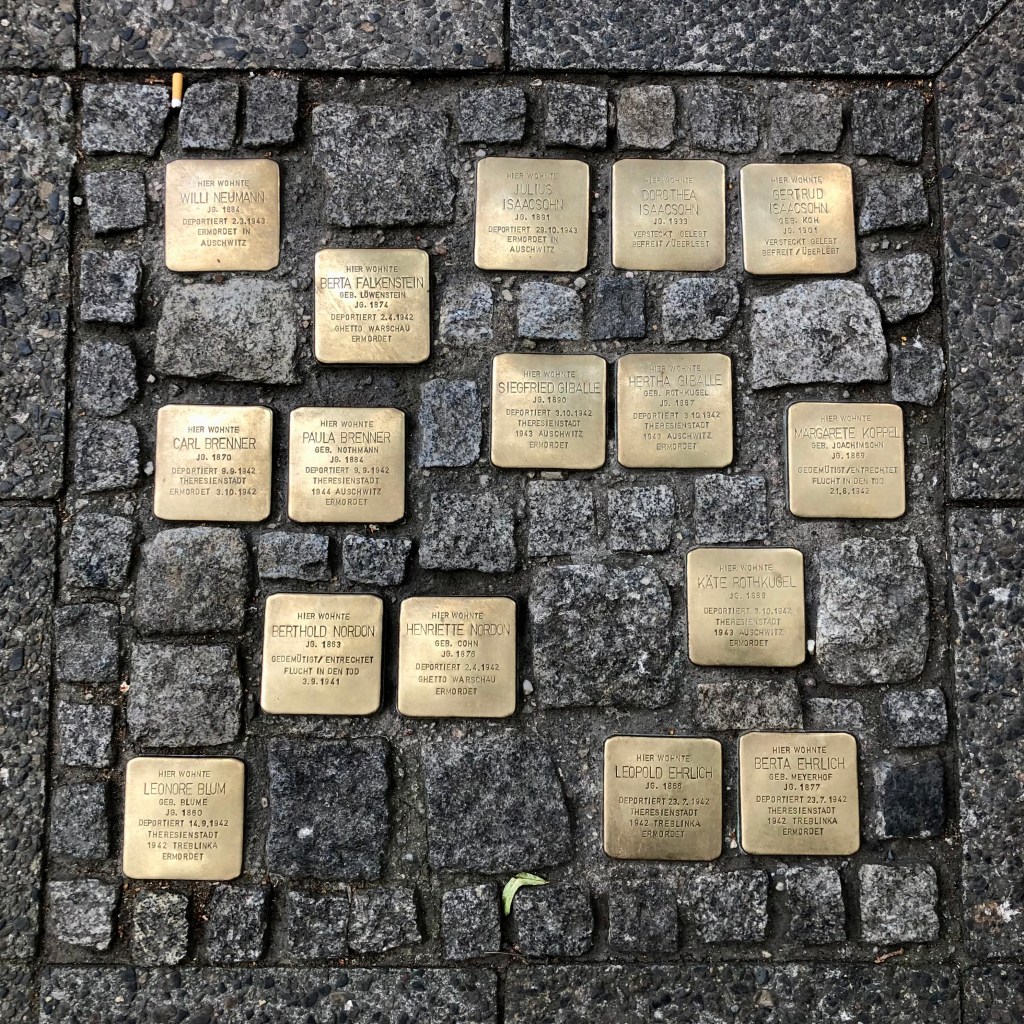

“Truth speaks from the ground” Anne Michaels wrote in Fugitive Pieces. I have always felt this since my first visit to Berlin in 1990. I remember wandering through the recently gentrified area around Hackescher Markt excited by its contemporary art galleries but wholly unaware of its history as a Jewish quarter from which thousands of Jews were rounded up and deported. But “… as the day wore on, I became increasingly aware of an uncomfortable sensation rising inside me. Something seemed to be seeping up from the pavement through my feet and weighing down my legs. It rose further, turning my stomach hard. By the time we stopped at a café, it had reached the level of my heart, at which point it spilled out in a huge wave of sobs…” (IMGS p.153)

Maybe that is why one sculpture spoke to me so strongly at Berlin Art Week’s POSITIONS exhibition housed in the long-disused hangar of Tempelhof Airport, site of the Western allies’ 1948-49 ‘Berlin Airlift’ in response to the Soviet Blockade.

I didn’t get the name of the artist (apologies), but to me their work brilliantly, wordlessly captures what I instinctively feel about being in the unique and extraordinary city that is Berlin, where past meets present with a potency that can’t be ignored.

For NEWS of forthcoming events in England and Germany, please see my website: www.angelafindlaytalks.com

To receive my NEWS straight into your email inbox, please SIGN UP to my NEWSLETTER