As I write this blog, I am holding in my thoughts and heart all who are suffering, grieving, lonely, lost, anxious, frightened, helping, serving, or dying and all the infinite shades of individual human experience that fall between.

Like for some, but unlike for so many more, my rural little Covid world of the past 5 weeks has been a haven of sun-filled peace. Such is the stillness that you can almost hear buds bursting into bouquets of blooms as Spring rustles through the land like a breeze. Woods carpeted in white and blue have become cathedrals for choirs of birds filling the daily Sunday silence with song. Time is no longer measured by clock hands and calendars, but by the gradual emptying of a fridge shelf or the clapping hands on the pavements that announce another week has passed.

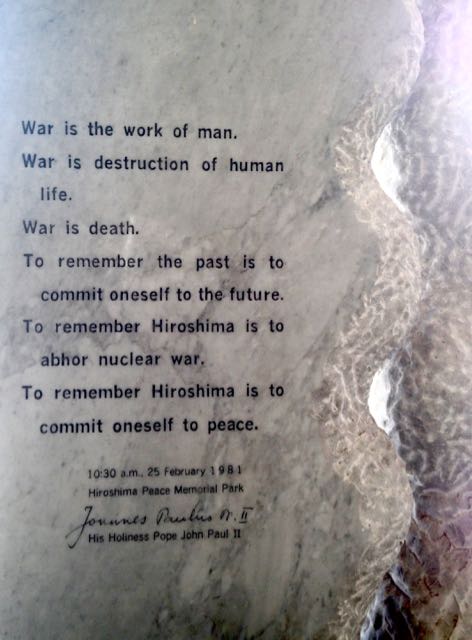

As if from another world, packages of numbers wrapped in the language of war drip-drip-drip-feed death, tragedy, fear and devastation into our days rippling the peace like a faulty tap. Are we at war with Covid-19? Is our sole purpose in the face of a cruel enemy that is attacking all we have come to know and value as “normal,” to defeat it? War requires strategies to target and vanquish an adversary through killing. But, as Angela Merkel said in her address to the nation on 18thMarch, the Covid-19 pandemic is a war without a human enemy.

I find it interesting and heart-warming that 99-year old Captain Tom Moore, an army veteran who fought in the world’s largest war, has become Britain’s inspiration and symbol for how to face the Coronavirus. In total contrast, both to armed conflict situations of war and the language used by several governments, he is not fighting to kill off something. By completing lengths of his back garden, he is walking to help our dedicated services save lives.

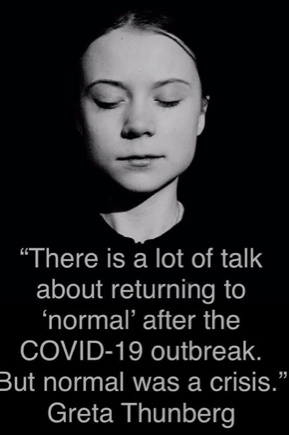

I have to confess that there are moments when I almost dread the day Covid-19 is “sent packing,” as Boris Johnson blustered before the virus robbed him of his usual air, and things return to ‘normal’. Of course I want a rapid end to the huge and relentless suffering of so many. But I don’t want us to go “back to normal.” I don’t want the war metaphors to continue but now with triumphant declarations of victory. For Covid-19 has not just been a vile enemy and bringer of death and misery. It has also been a huge teacher, a creator of peace, a unifier of communities, a friend to nature, a highlighter of the fissures in our society and a persistent pointer to the most vulnerable, the most needed and the most brave. Covid-19 is a killer, yes, but as anyone who has been close to the death of a loved one will attest to, it is also guiding us to our hearts.

Many people have said it much better than I can, either in this or my last blog. In my opinion, one of the most insightful and erudite writings on the subject is the essay The Coronation by Charles Eisenstein. In it he says: Covid-19 is showing us that when humanity is united in common cause, phenomenally rapid change is possible. None of the world’s problems are technically difficult to solve; they originate in human disagreement. In coherency, humanity’s creative powers are boundless… Covid demonstrates the power of our collective will when we agree on what is important.

I feel deeply and passionately that there is a much bigger picture to the close-up snapshots we are getting from around the world. We are standing before a phenomenal chance for change. A unique opportunity to not go back to the “normal,” which was neither just, nor sustainable, nor even working for the majority of the global population. As Charles Eisenstein asks: For years normality has been stretched nearly to its breaking point, a rope pulled tighter and tighter… Now that the rope has snapped, do we tie its ends back together, or shall we undo its dangling braids still further, to see what we might weave from them?

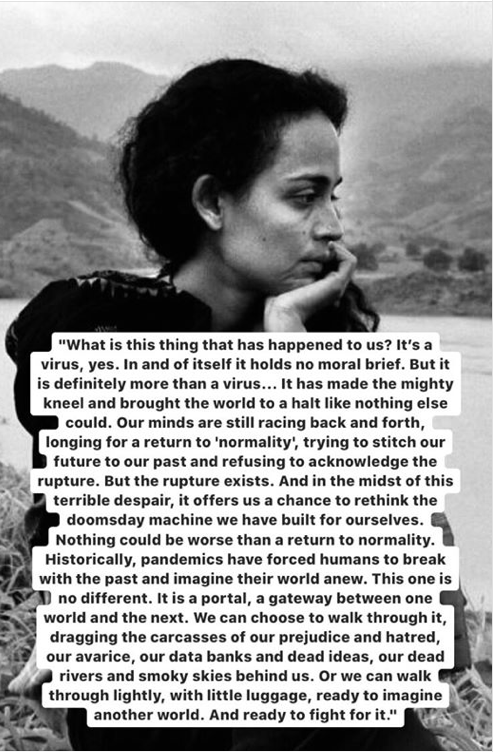

The Indian author, Arundhati Roy, says much the same in THE WAY AHEAD:

The writing has been on the wall for a long time. I sincerely hope Covid-19 will make it impossible for these ways of thinking to be brushed aside and ignored as the domain of dippy-hippies, whacko scientists, alternative dropouts, idealists, artists or activists. I pray that during this prolonged pause enough of us can shift our values and priorities fully into the camp of those we are currently embracing, not just as individuals but also as a nation. As I have frustratingly learned from decades of campaigning for prison reform, the political impetus to change will only come from widespread public insistence and/or inspired and wise leadership. I don’t yet know what exactly I, what we as individuals, can do and I welcome all suggestions. But maybe a good starting point is to follow New Zealand’s Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern’s encouragement to “Be strong, be kind.”

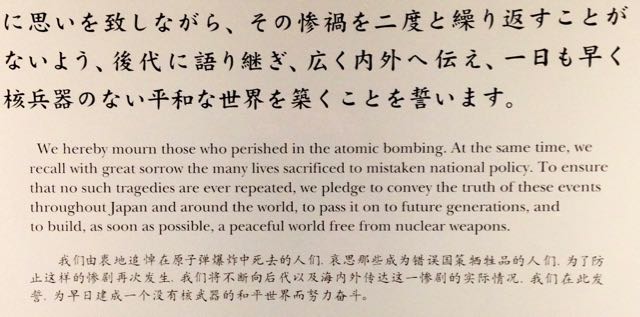

Some further opinions:

Penguin is publishing essays about Covid-19 by their leading authors every Monday, like It’s all got to change by Philp Pullman and A New Normal by Malorie Blackman

The pandemic is a portal by Arundhati Roy

Covid-19 and the language of war by ADRIAN W J KUAH AND BERNARD F W LOO

Coronavirus and the language of war New Statesman

Coronavirus: How New Zealand relied on science and empathy BBC News

The Coronation by Charles Eisenstein as a podcast and as a PDF file

George Monbiot talks about Coronavirus