If you haven’t yet seen Jesse Eisenberg’s latest film, ‘A Real Pain,’ I can only urge you to do so. Starring himself and Kieran Culkin [youngest son in Succession!], the pair play two estranged cousins who travel to Poland to fulfil the wish of their recently deceased, concentration camp survivor grandmother for them to visit her former home. It’s essentially a road movie and extremely funny. But the context of the Holocaust and the attempts of third-generation Americans to come to terms with it, makes it also profoundly moving, thought-provoking and important.

Millions of people world-wide are still grappling with the aftermath of those appalling years of Nazi rule. More, rather than fewer, stories of survivors and first-hand witnesses are coming to light told by descendants who have finally found ways to articulate what their forebears couldn’t. My own, In My Grandfather’s Shadow, published in 2022, is testament to the painful process of peeling back the layers of incredulity in which the extremes of both cruelty and suffering are wrapped. For many, it is justifiable to judge or blame ordinary Germans for not speaking out or revolting against the wrongness of what was happening in clear sight. Despite acknowledging their justified fears, it would have been the right thing to do.

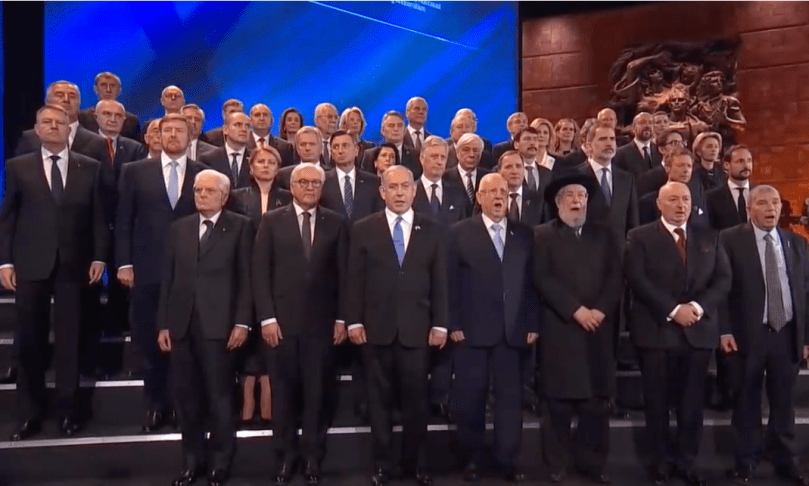

As we approach Holocaust Memorial Day marking the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz by Soviet forces in 1945, we are asked to remember the horrific consequences of the crimes that, in part, were enabled because people did not speak out. We will once again repeat the heartfelt ‘Never Again’ that has been chanted like a mantra over the decades. But is it enough?

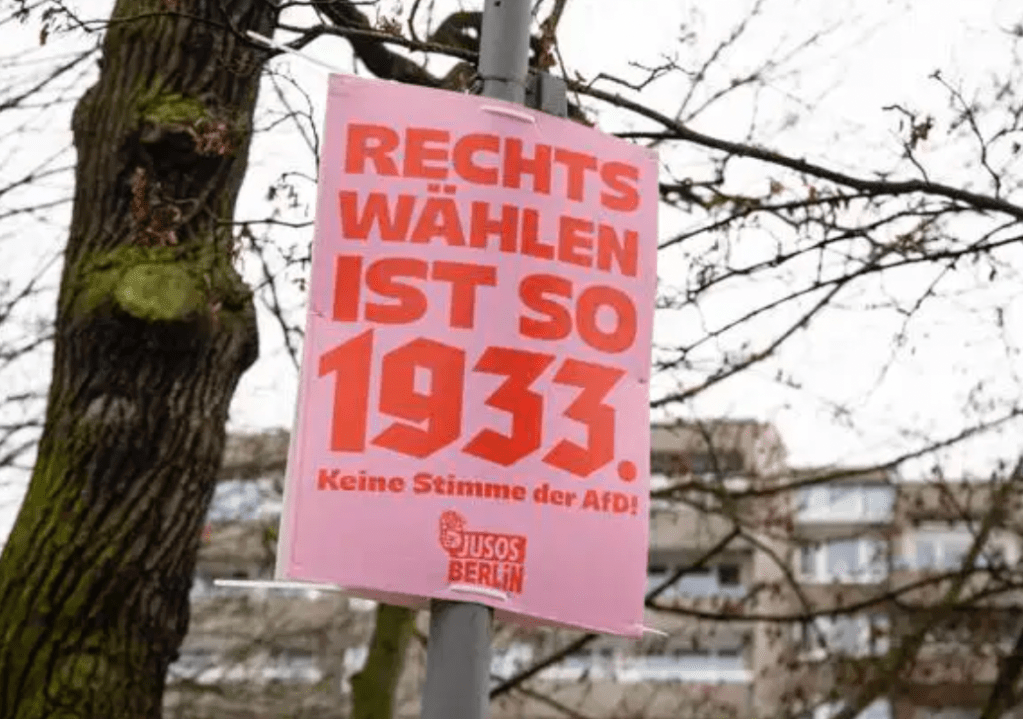

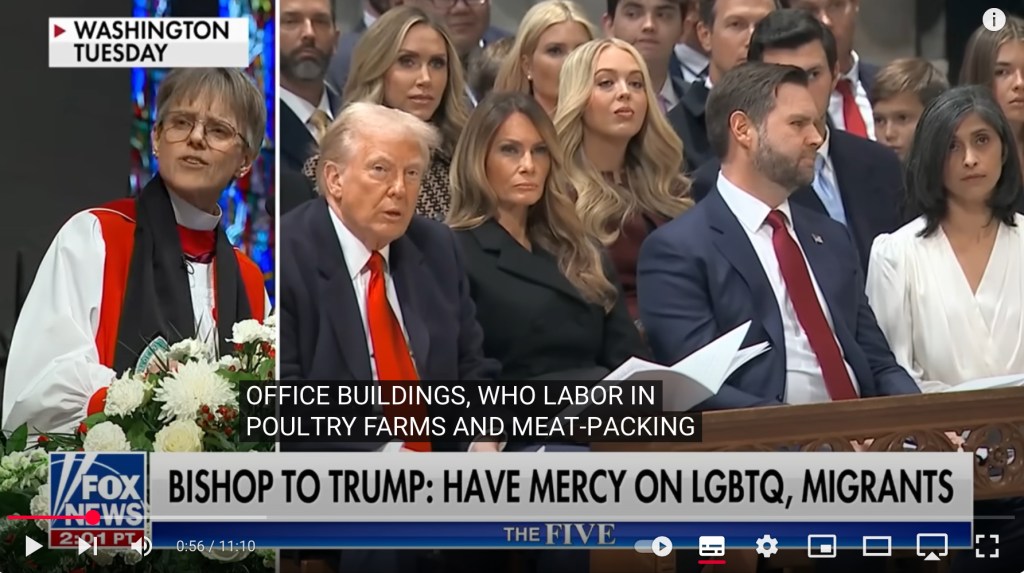

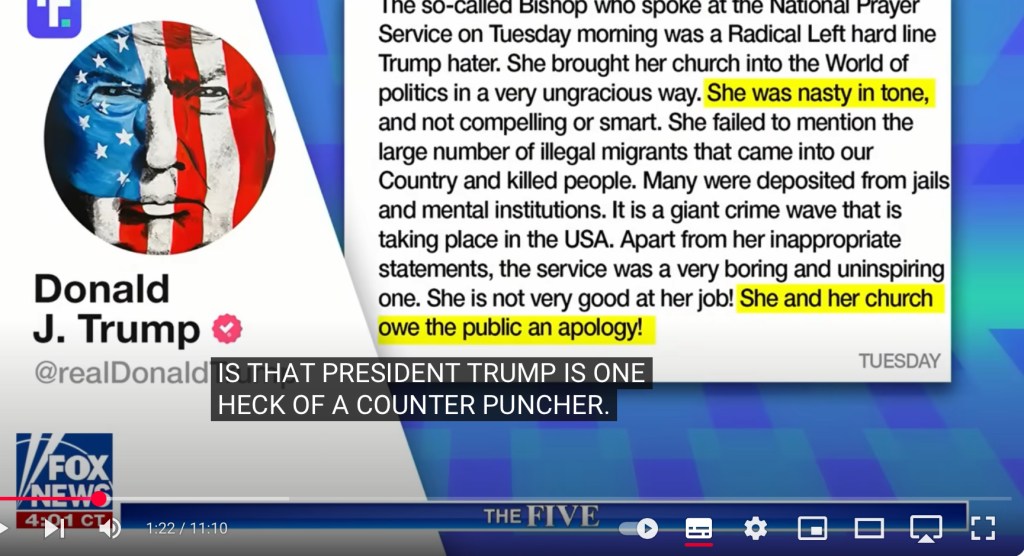

Across the globe, the roots and shoots of far-right policies are taking hold with renewed vigour. In highly vigilant Germany, ‘Voting right-wing is so 1933’ is a campaign slogan for left-wingers. But calling out discrimination and anti-immigrant policies, becoming an ‘upstander’ rather than a bystander has become increasingly perilous, even a danger to life. I wonder how Bishop Mariann Budde’s recent controversial sermon at the inaugural prayer service at Washington National Cathedral will play out. Referencing immigrants and LGBTQ+ individuals among others, she calmly but directly asked President Trump “to have mercy on the people in our country who are scared now.” Will she be cancelled, trolled, fired, discreetly removed from her post? So far she is refusing to apologise for speaking her truth. Was it brave, wise, right? Or, as he and his supporters claim, ‘nasty, woke, inappropriate’ and she a “Radical left hard line Trump hater”? Bizarre as it sounds, by seeking a path of compassion, did she inadvertently shame and dent an ego as big as the world?

As someone with (non-Jewish) German roots, I feel like it is both in my DNA and a conscious personal responsibility to speak out in the face of a perceived injustice or wrongdoing. However, I am beginning to feel an even stronger impulse. In these times of widespread latent and reactive vitriol and rage, I have started to listen into the other side’s point of view rather than – or at least before(!) – slating it. To create a tiny pause, a space between the attack and counter-attack model so many discussions rapidly descend into. It’s like stepping back from an easel when you have been immersed in some detail in order to see the whole picture. For when we speak out against something with conviction but without seeing the back story behind the other’s conviction, we are basically assuming a moral and intellectual high-ground that imparts the message that ‘they’ are wrong (inferior) and ‘we’ are right? This never goes well! Trump’s return to the White House proves that.

Decades of trying to comprehend the behaviour of ordinary Germans eighty or ninety years ago have revealed to me that many of them won’t have been so different to many of us today, i.e. more concerned with their own lives – milking cows, running businesses, keeping children warm and fed – than politics. Looking away, keeping stumm becomes a basic survival tactic. But the outrage humans feel in the face of endless discrimination, inequality, injustice, harm can rapidly turn to despondency and disaffection when we realise we can do little more than sign a petition or share a rant on social media or among friends. Eventually we might become numb, at worst immune to the wrongdoing. I know that I personally read, watch and listen to the news far less than I used to because the drip-feed of madness, badness and sadness feels toxic and induces inertia. I have no idea if this is maturity, complacency, disheartenment, a nauseating lack of humour or an equally nauseating sense of self-righteousness, but I have lost some of my more outspoken tendencies and anger at the world and replaced them with something that is hopefully more productive but still relevant to these times.

My prison work showed me that the most valuable action I could offer prisoners was to listen and to hear them. Not just their stories, excuses and justifications, but what came before. The drivers of their behaviour. With their defences down, trust, compassion and understanding could grow. Attitudes and actions quietly changed without them being shown to be wrong.

I am not sure if this is the right way to go in general life. The story of the Zen / Chinese Farmer comes to mind with its ‘We’ll see…’

It’s certainly not a quick-fix solution. But maybe it’s a tiny antidote to the constant stoking of anger? A drop towards the creation of a kinder world in which wider discourse and a greater tolerance of difference are possible. And ‘Never Again’ regains its urgency and weight.

A few links to that don’t necessarily reflect my views, but are accessible sources to pursue your own research.

A Real Pain Review

A Real Pain Trailer

Germany’s present is not Germany’s past by Katya Hoyer

Who is Mariann Edgar Budde, the bishop who angered Trump with inaugural sermon?

‘I am not going to apologise’: The Bishop who confronted Trump speaks out