‘Tis the season to remember… and yet, this year, for the first time, I forgot. Remembrance Sunday was almost over before I suddenly remembered to remember.

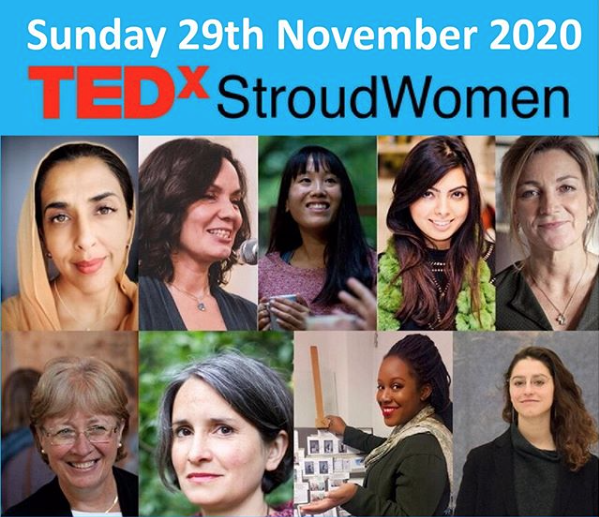

Locked down at home, I was definitely silent. But maybe the official 2-minute silence at 11am passed me by because in my talks and blogs I am frequently remembering. In fact, ‘looking back’ has become part of my identity, my expertise even. So much so that I have been selected, as one of nine speakers, to do a Tedx Talk on the subject: ‘Facing the past in order to create a fairer future.’ It’s an exciting opportunity though unfortunately lockdown has forced the proposed date of 29th November to be postponed until the spring. It will happen though… like so many other things in this disorientating Covid world in which we are currently immersed.

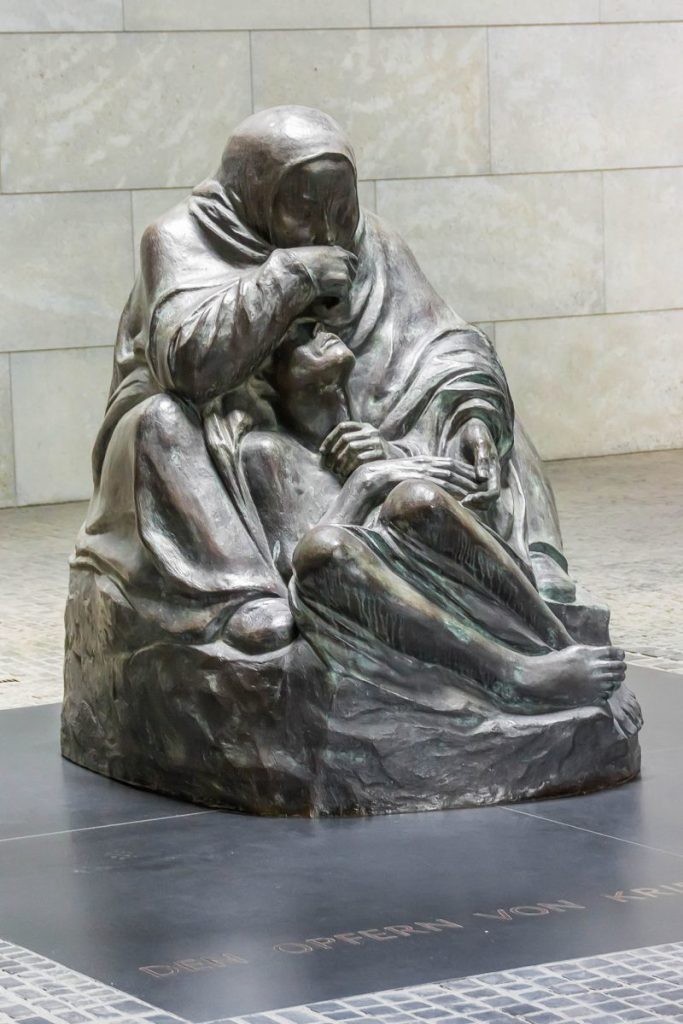

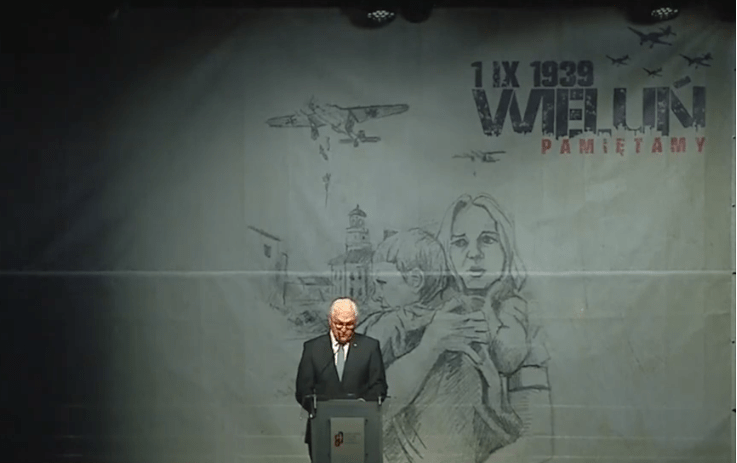

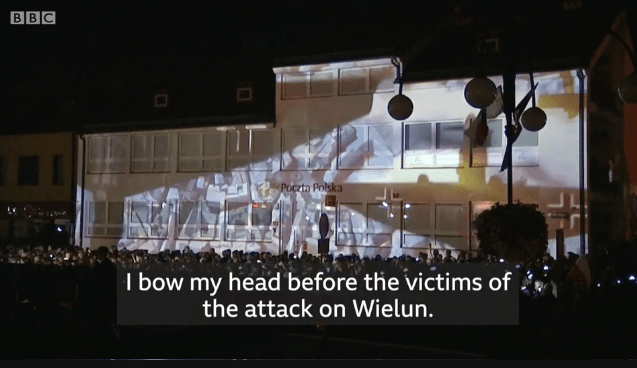

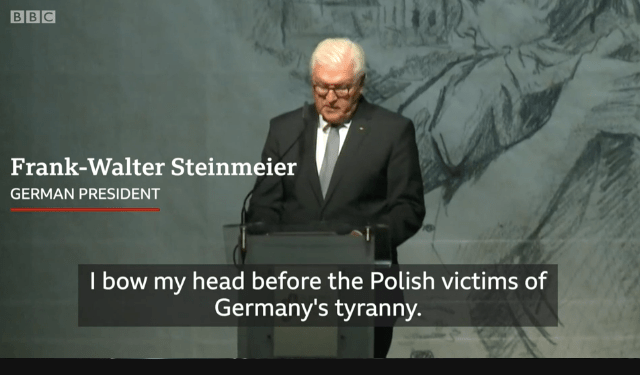

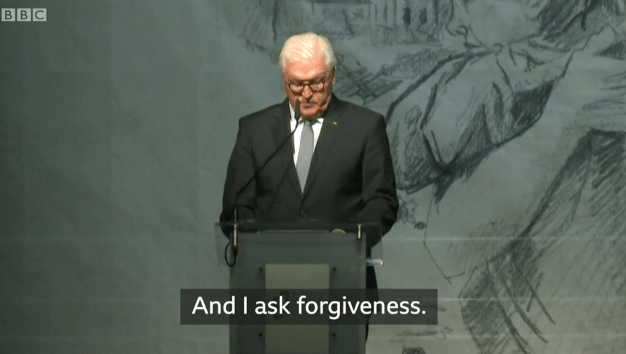

In the meantime, if you haven’t attended my talk on How Germany Remembers and would like to, there’s a chance to hear it online on Friday 13th November at 11.30am. It is being hosted by the National Army Museum in London where I spoke last year. You can read more about it here and you can register for free here.

But back to remembering… or forgetting in my case. Maybe there are some of us who feel a little tired of remembering. Or maybe it’s the national narrative we tell ourselves each year, that is tiring. This is one of the points made in Radio 4’s ‘Our Sacred Story’ in which Alex Ryrie, Professor of the History of Christianity at Durham University, suggests that the Second World War is both our modern sacred narrative as well as the shaper of our collective sense of what constitutes good and evil.

This summer we celebrated the 75thanniversaries of VE and VJ Day. In fact, we’ve done loads of national remembering over the past years. So aside from Remembrance fatigue, I’m wondering if Covid’s restrictive squeeze on lungs, lives and events alike, is also impacting what and how we remember. Lockdown has been turning mindsets inwards, shifting focus and values onto all that is immediately around us – family, gardens, quiet streets or empty skies. Maybe this new way of being is merging effortlessly with the existing sub-stream of thought that strives for essence rather than glitzy, sparkling veneer.

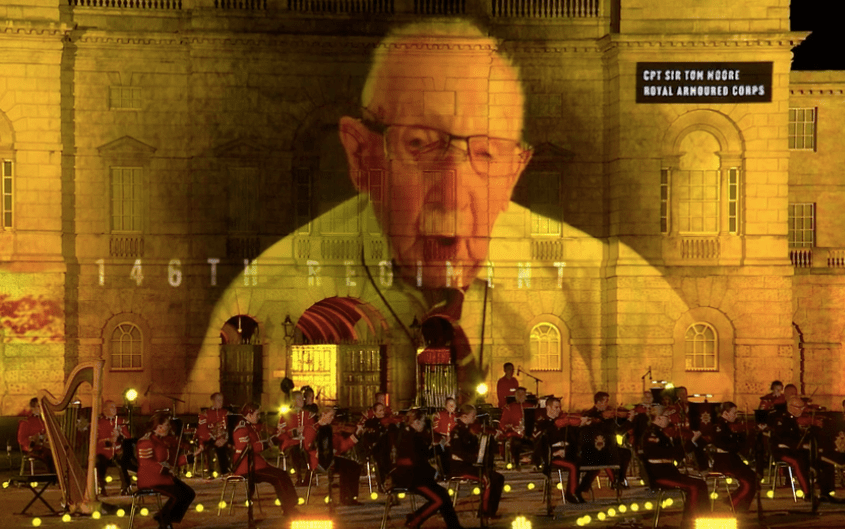

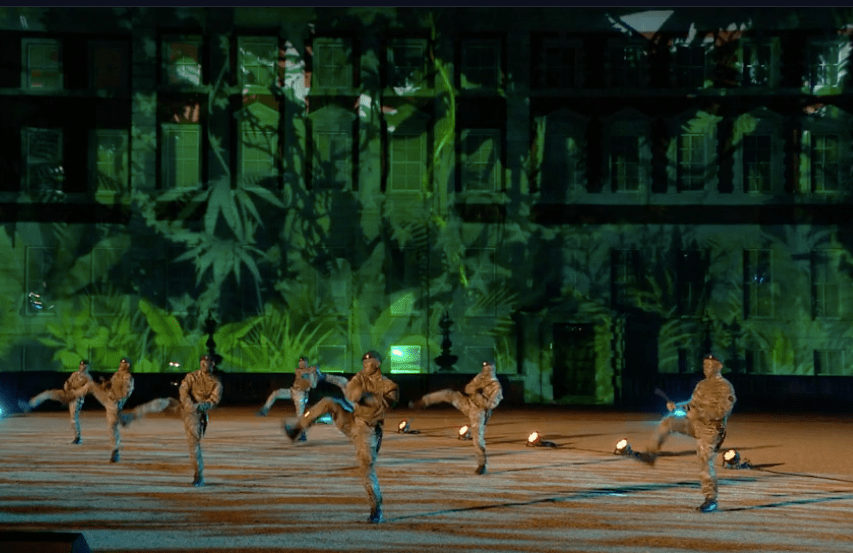

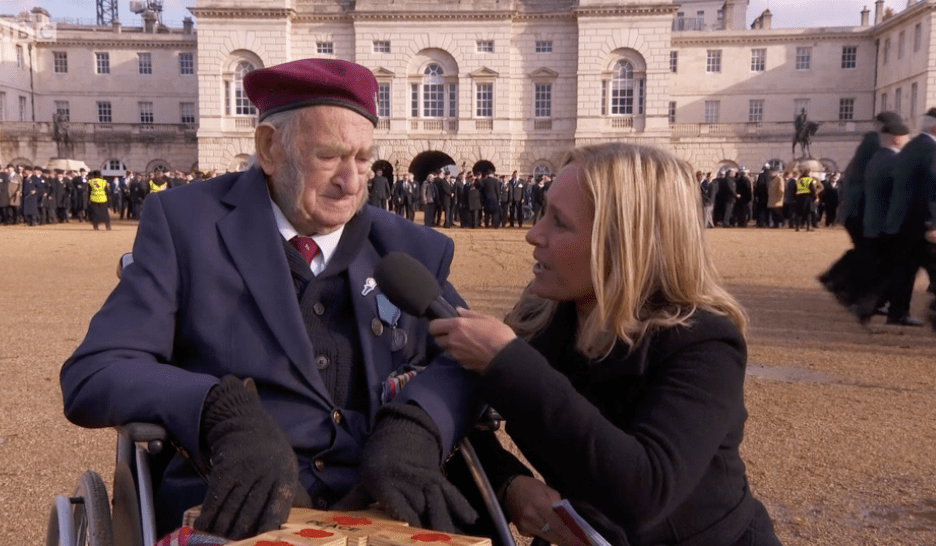

Looking at the BBC coverage of Remembrance Sunday, it is clear that even our mainstream institutions of commemoration are being forcibly stripped of excess. I salute the efforts of all involved in trying to evoke the all-too familiar rituals, yet nothing could distract from the extraordinary visuals of sparsity. Watching the morning ceremonies at the Cenotaph, one could be forgiven for not knowing where one was. The eerily still Whitehall dotted with a few socially-distanced, poppy- and wreath-bearing dignitaries resembled a set construction of a movie whose budget couldn’t stretch to more actors. And in Westminster Abbey, the Queen, bless her, hatted and masked up in black, couldn’t help but look a little like Darth Vader as she gently touched the white myrtle wreath that was then laid by a masked serviceman upon the Grave of the Unknown Warrior.

I couldn’t sit through the empty-seated Royal Albert Hall festivities that in the past have both grated and made me cry against my will. Instead, I sought the essence of remembrance in other areas. I soon found it in the podcast, We have ways of making you think. In their Episode 203 on Remembrance, historian James Holland and comedian Al Murray were in conversation with Glyn Prysor, former historian of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Between them they brought to life the history of the ubiquitous white headstones that fill acres and acres of land both here and on the continent.

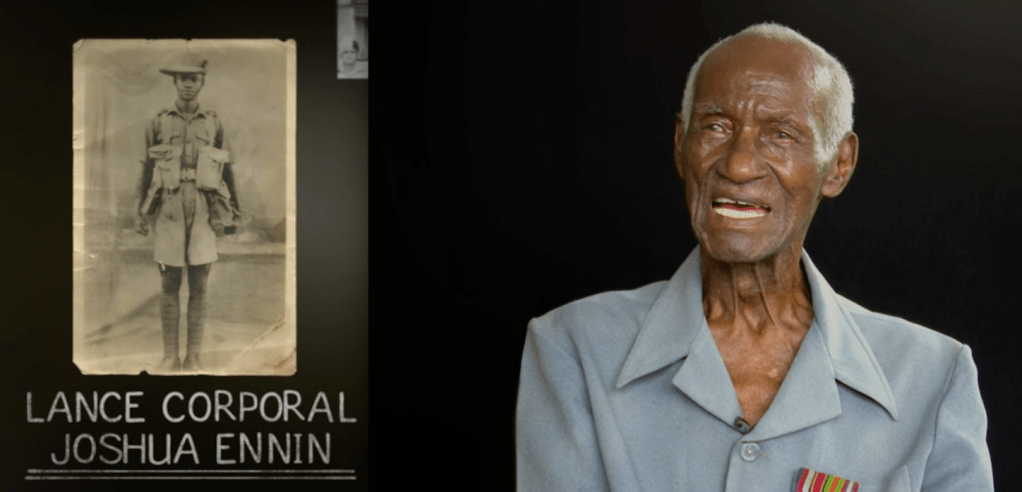

Set up in 1917 while World War One was still raging, the process of burying in the region of a million war dead, half of whose remains were missing, demanded a very new way of thinking. In a departure from the Victorian hierarchy of worthiness that extended into death and resulted in the common man just being ‘bunged’ into a mass grave, the Commission made a move towards inclusion. It wanted to evoke the sense that everyone had contributed to the war and everyone was equal in death. The outcome was a uniform design for all headstones that would make no distinction between wealthy and poor. This was of course deeply controversial. Individuality would only be marked through the listing of name, rank, unit, regimental badge and date of death. An appropriate religious symbol could also be added, or not. And a space at the bottom was dedicated to personal messages from family members, some of whom would never be able to travel to the continent to visit the graves of their loved ones.

Covid has been highlighting the need for a similar leveling process across our hierarchies of wealth, fairness and opportunity. As in war, it is the personal losses and tragedies that will far surpass and long outlive the victories or shenanigans of the politics. In that vein, I found the essence of remembrance in an inscription spotted on a war grave in Bayeux:

Into the mosaic of victory, our most precious piece was laid.