Ok, here’s a challenge for a rainy day.

Can anybody name one good reason why this country repeatedly does nothing about the state of our prisons? Can you give me any single benefit to us, as a nation, of keeping people in institutions that have repeatedly been condemned for their wholesale ineffectiveness?

Since 2001 when I got involved in Britain’s Criminal Justice System having worked in Germany’s for 6 years, I have heard one government-appointed Chief Inspector of Prisons after another – from the judge, Sir Stephen Tumin, to the army officer, Sir David Ramsbotham, to the current retired senior police officer, Peter Clarke – denounce the conditions in our jails. All their reports reveal systemic failures, appalling levels of filth, readily available drugs, lack of educational opportunities and deeply disturbing practices that arise as a result of overcrowding.

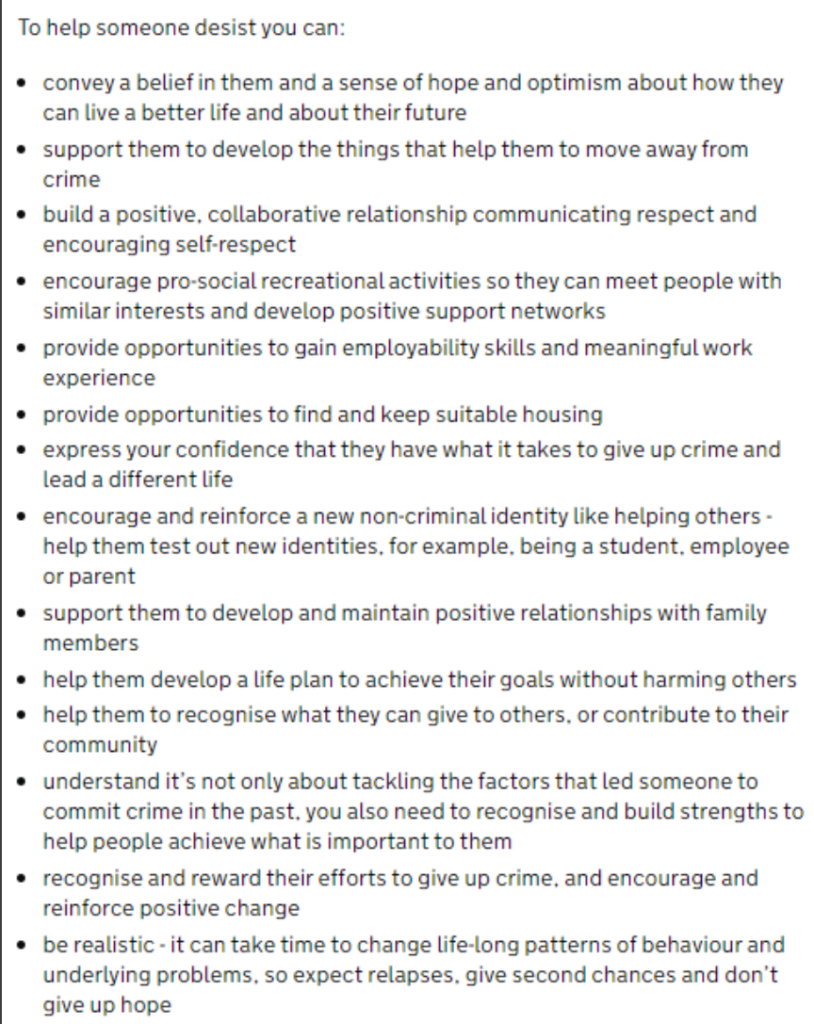

Since the 40% budget cuts of 2010, things have only got worse. 25% to 1/3 of prison officers and staff were lost. This has led to prisoners being left languishing in their cells for up to 23 hours a day because there are not enough officers to unlock doors and take them to education, employment, anger-management or drug rehabilitation courses – all things that have been proven to help prevent re-offending. I experienced it myself in HMP Belmarsh when I was Arts Coordinator to Koestler Arts. We raised the money for a 5-week art project, we provided the artists, the materials, we organised the practicalities and we then showed up. But the prisoners didn’t. Because the officers didn’t have time to deliver them. It is one of the reasons I gave up my front line work and focused my attention on raising awareness of what is going on.

Now in 2020, I would finally like to understand the apparent logic behind the criminal waste of time, money, opportunity and human lives. And why we, as a nation, allow it to continue.

What is the block that is preventing the British public, the politicians, the Justice Secretaries – of which there have been seven in the past ten years – from recognising the illogic of depriving people of their liberty with the justification of punishment or deterrent, only to then make everything else infinitely worse? Surely it is not rocket science to comprehend that placing people… and they are people… in squalid, overcrowded environments in which they are likely to become more brutalised, embittered and frustrated; in places where they may well acquire a new drug habit, learn hot tips for new criminal methods, possibly self-harm or commit suicide; in places where they have limited or no access to the services, education and general help they need… cannot produce positive results? How can any reasonable person not see that ejecting them back into society after their sentence with £47.50 in their pocket, a criminal record – and sometimes a TENT! – is not going to stop them from re-offending, possibly within days? How is this supposed ‘tough on crime’ approach to people, who often come from catastrophic, traumatic or hugely disadvantaged backgrounds going to make our communities safer?

I am no economist or mathematician but let’s just look at 2 figures:

1. The Prison Service budget is £4.5 billion per year.

2. The cost of re-offending is £18 billion.

Let’s look at 2 more:

1. 70% of prisoners suffer from some sort of mental health issue.

2. 50% of prisoners are functionally illiterate.

The logic is there in black and white, in the figures. So why this dug-in-heels resistance to changes that embrace methods that have been proven to work? Not least Restorative Justice.

This week, in his last report as Chief Inspector of Prisons, a weary looking Peter Clarke, like so many of his predecessors once again explained the detrimental impact our system has on the mental health of prisoners. Once again he reported rubbish and rat-filled environments, apparently ‘so dirty you can’t clean it’. Once again he described the overall failure of managers who are proud of their data-driven and evidence-based methods but have rarely been inside prisons to ‘taste it, smell it.’ Clarke expresses similar bemusement to me as to why these damning reports so often come as a surprise to the management of the Prison Service. This has been going on for years! We may not be ‘world-beating’ in the appallingness of our prisons but we certainly are close to, if not at the top of the European table of failure.

As Chris Atkins says in his new book A Bit of a Stretch, our prisons have become little more than ‘warehouses’ for storing offenders. Justice Secretaries, often lacking any background in law, let alone prisons, announce new initiatives with great fanfare, but nothing gets done and after a year, they move on.

How I wish we could have a minister like the actor Hugh Laurie’s Peter Laurence, in the brilliant new BBC series, Roadkill. Laurence is deeply flawed as a man and corrupt as a politician, but in his newly appointed position as Justice Secretary, he at least verbalises the obvious question: Why are we wasting so much public money on a policy that’s not working? ‘Everyone knows the prison system is grossly inefficient,’ he tells the wholly resistant, thankfully fictional, female Conservative prime minister. ‘So I’m going to shake things up. Justice deserves that.’

And it does. But he will fail. Because it is not just the right-leaning politicians who want to stick to our punitive approach. It is also the British public. In the series, both their attitudes are revealed: ‘We lock criminals up and throw away the key… in the interest of public safety… We’re famous for it… It’s our nature… It’s our bond of trust between the Conservative party and the public…’

Covid-19 has of course made conditions even worse. Some prisoners are locked in their cells for 24 hours a day, and for several weeks at a time in what amounts to solitary confinement, as Clarke points out. Of course that leads to the ‘more controlled, well-ordered’ environment the Prison Officer Association is relieved to have. But what does it do to the people inside? Clarke is convinced there must be an exploration of other ways to do things, safely. After all, ‘Are we really saying we are going to keep prisoners locked in their cells for another 3 months… 6 months… a year?’

After my talks on Art behind Bars in which I reveal the shocking but oft-printed statistics of our prison system’s failures, people frequently come up to me and say “Gosh, how awful, I had no idea.” Well maybe with all the upheaval of Covid-19, it really is time for the public to gain an idea of the horrors that are being perpetuated in their name; in the interest of their safety. Of course we can stick with the old approaches, but at our peril. For who pays the price? Don’t think it is just the prisoners and their families who are punished. It’s all of us. We make ourselves less safe. We make ourselves less just. But above all, we make ourselves complicit in a system that is less than humane.

If you would like to do something to help bring about a shift in attitude and policy, you can write to your MP. You can support the important work of The Prison Reform Trust or the Howard League for Penal Reform. Or any of the charities offering help to prisoners and their families. Or you can look at the wonderful work of my favourite charity, The Forgiveness Project, and their excellent and effective prison RESTORE programme, that I have both witnessed and on one occasion co-facilitated.

Links to follow up

Prisoners locked up for 23 hours due to Covid rules is ‘dangerous’ – BBC News

BBC Newsnight 20.10.20 with Chief Inspector of Prison, Peter Clarke Start at 21.27 mins

Chris Atkins A Bit of a Stretch: The Diaries of a Prisoner at Wells Festival of Literature

Roadkill on BBC player

The Guardian view on failing jails: an inspector’s call