Reflections on: IN PROCESS… a life, a film, a book, an exhibition, The Vaults, Stroud. Sunday 19th October, 11am-5pm and by appointment until 1st November.

“We must, we must, we must increase the bust.

The bigger the better, the tighter the sweater, the boys depend on us.”

I remember chanting that with my boarding school roommates as a teenager, elbows flung back in a futile attempt – in my case at least – to inflate our adolescent chests. Bigger was definitely better, or so we believed.

Skyscrapers, cars, salaries, houses… In so many areas of modern society, ‘big’ still equals ‘better.’ More followers, more likes, more headlines, more sales. The biggest countries led by the most powerful leaders and largest militaries make the most noise. And yet we know, quantity doesn’t equate to quality. Magnitude doesn’t always reflect meaning or value.

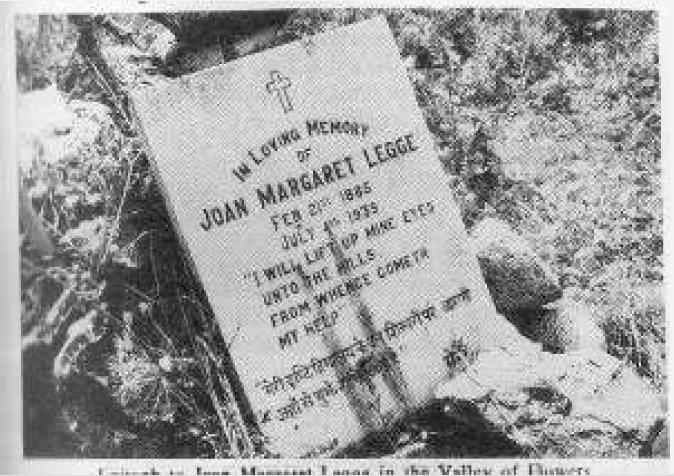

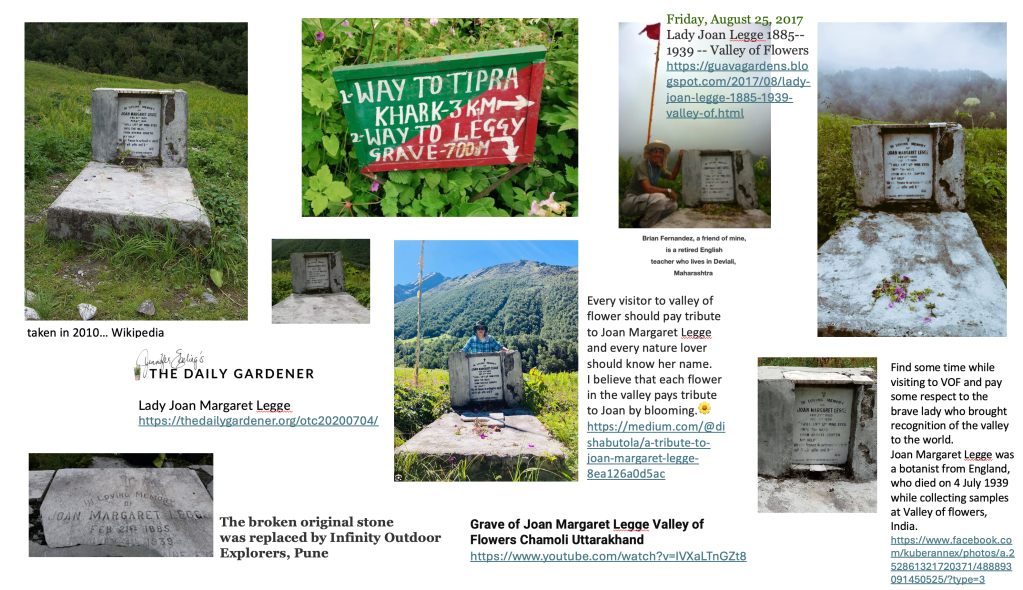

This idea – that bigger isn’t always better – is something I’ve seen reflected both in the trajectory of my great great aunt Joan’s life and in my own development as an artist. (If you are new to Joan’s story, please see my previous blogs for background.)

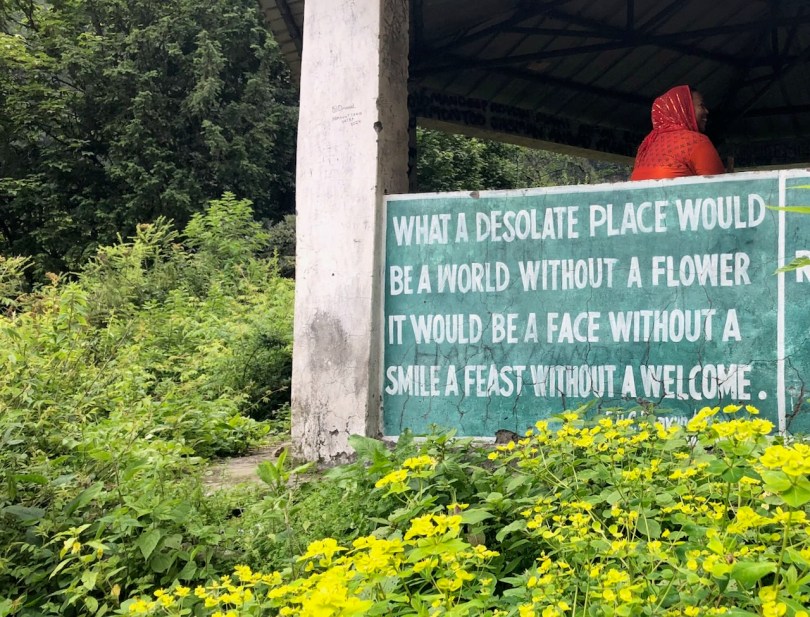

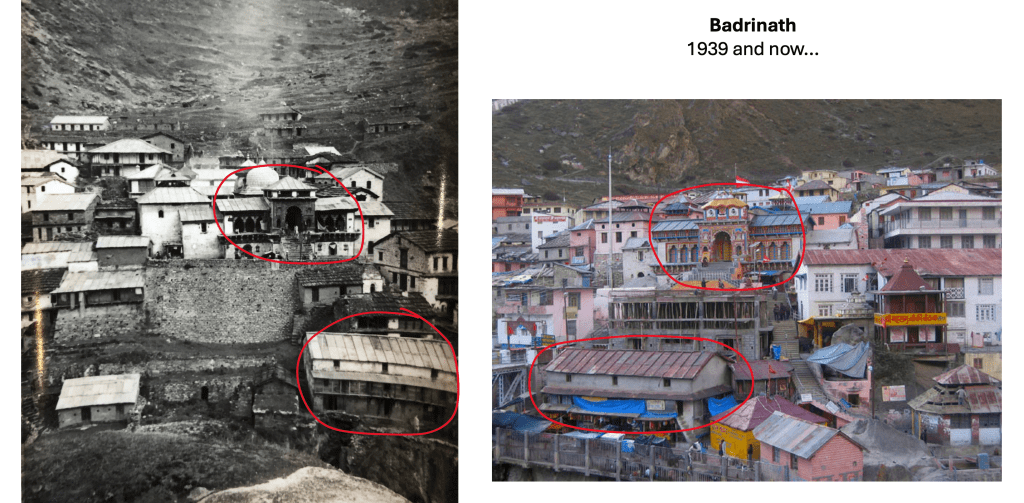

Joan grew up in a 147-room stately home in Staffordshire. Yet she spent her final weeks in a single, often soggy Meade tent pitched in a remote Himalayan Valley, surrounded not by grandeur but by shepherds, wildflowers and the sound of rain. She had traded scale for purpose. And her joy, it seems, had grown as her material load had lessened.

My own artistic journey has followed a similarly inverse curve.

I began large, unable to contain any drawing or painting within the boundaries of paper or canvas. My work spilled onto walls, first private then public, then grew further to fill stage backdrops for theatres or touring bands. Various mishaps including a paint-splattered boss’s car and a disastrous commission to paint the backdrop for INXS KICK album tour in 1987, which promptly cracked and fell off in large chunks when rolled up, nudged me toward the more forgiving surface of prison walls. There, no amount of damage could make the environment worse than it already was.

Years later, I turned my focus to canvases of my own, their size dictated by the available studio space and commercial considerations of galleries. And most recently, to works just 28x28cm – or smaller. I have replaced the vast audiences of art fairs with the quiet intimacy of just six or seven visitors at a time into the two vaults beneath my home in Stroud’s Cemetery.

Those vaults now house In Process… a deeply personal exhibition about Joan, her life and the resonance her death still holds for me, our family and small communities she encountered in India.

In one vault, where gravediggers once hung their tools and I now hang mine, visitors watch a short film projected into the open lid of an old trunk telling the story of Joan Margaret Legge.

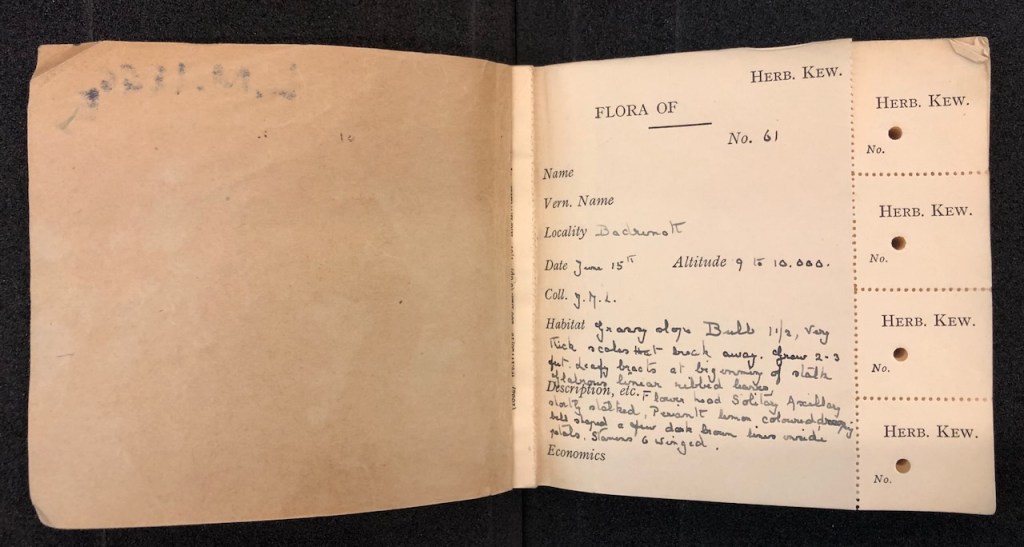

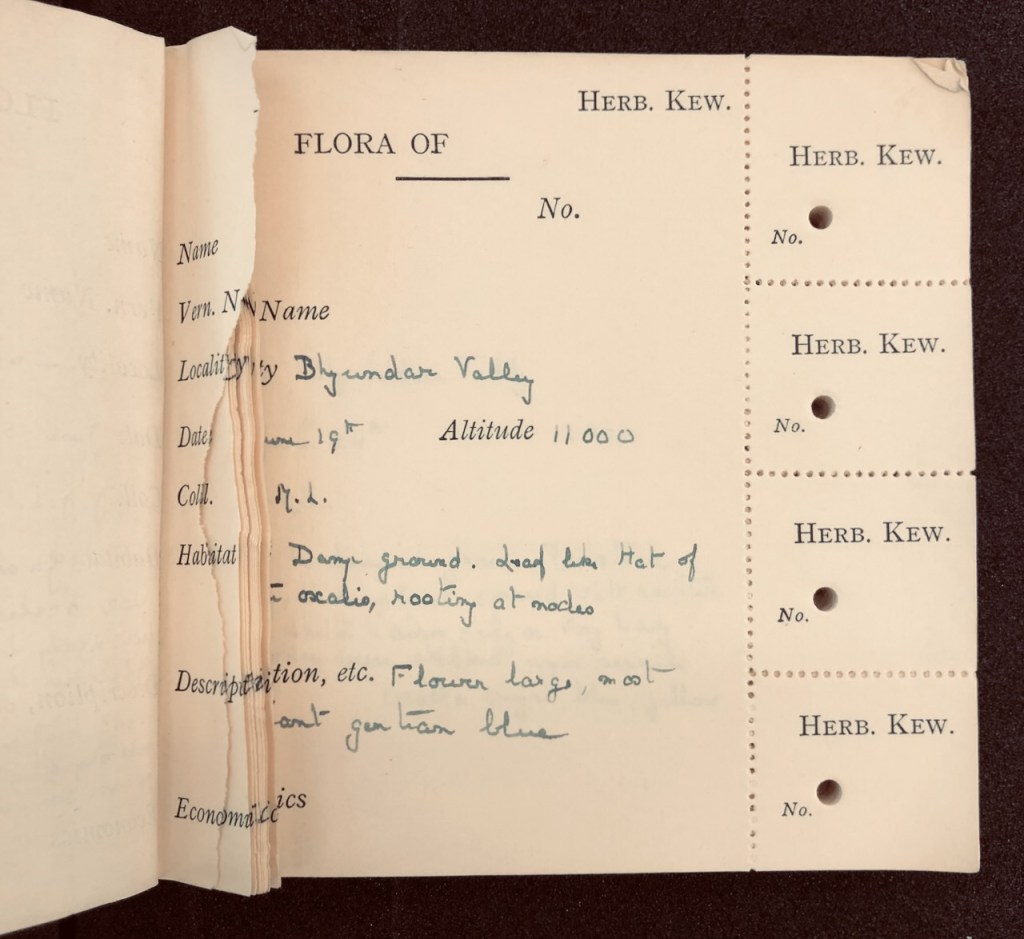

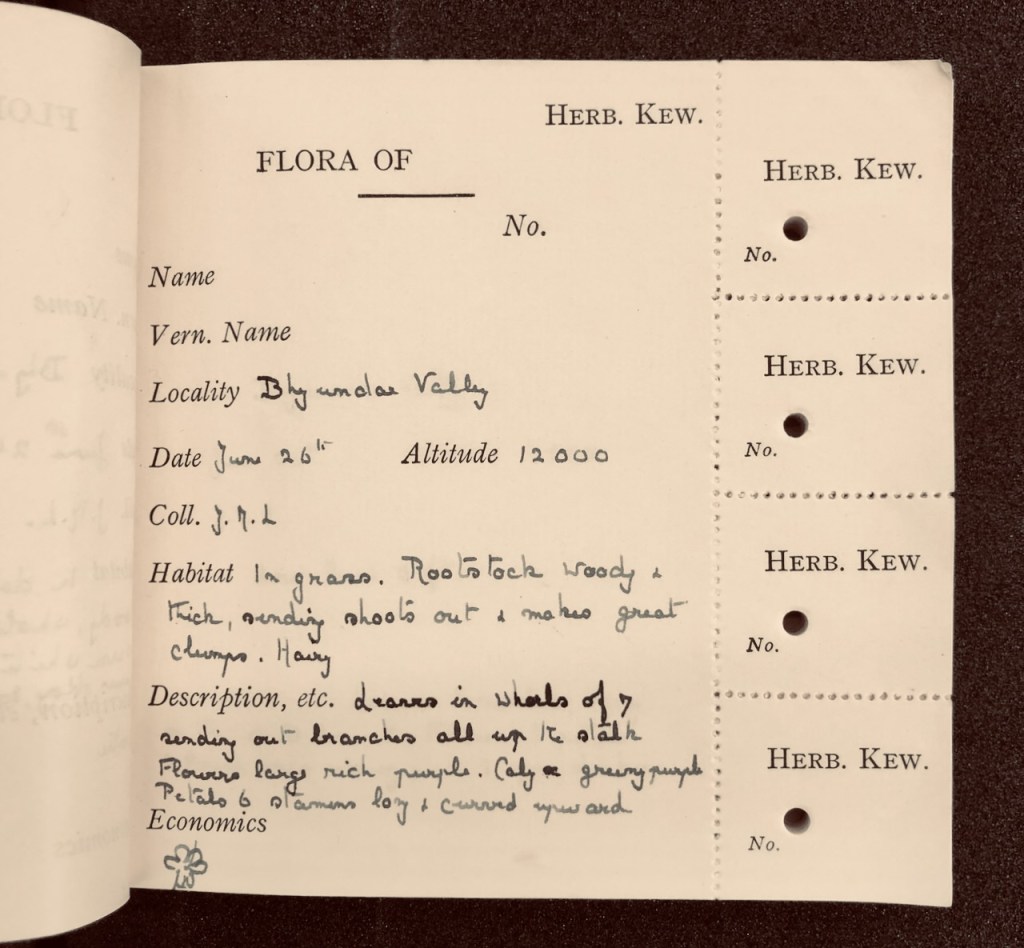

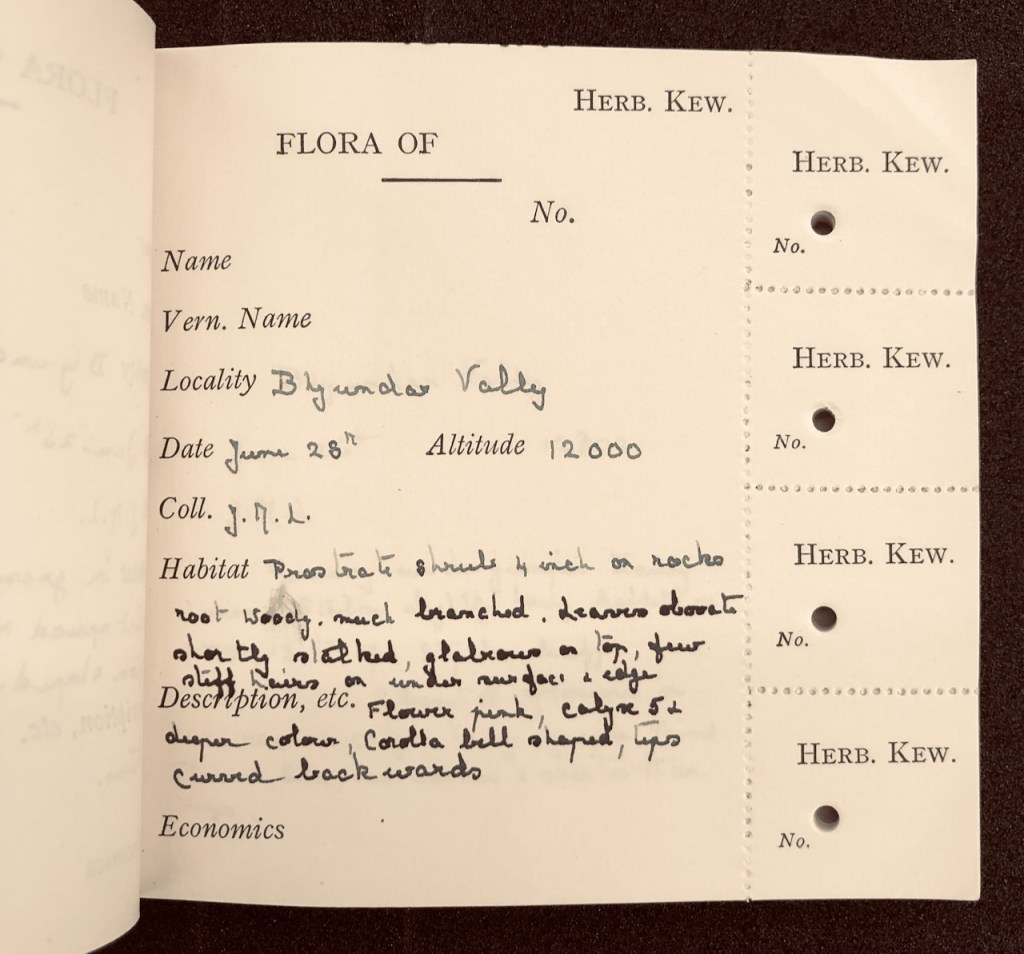

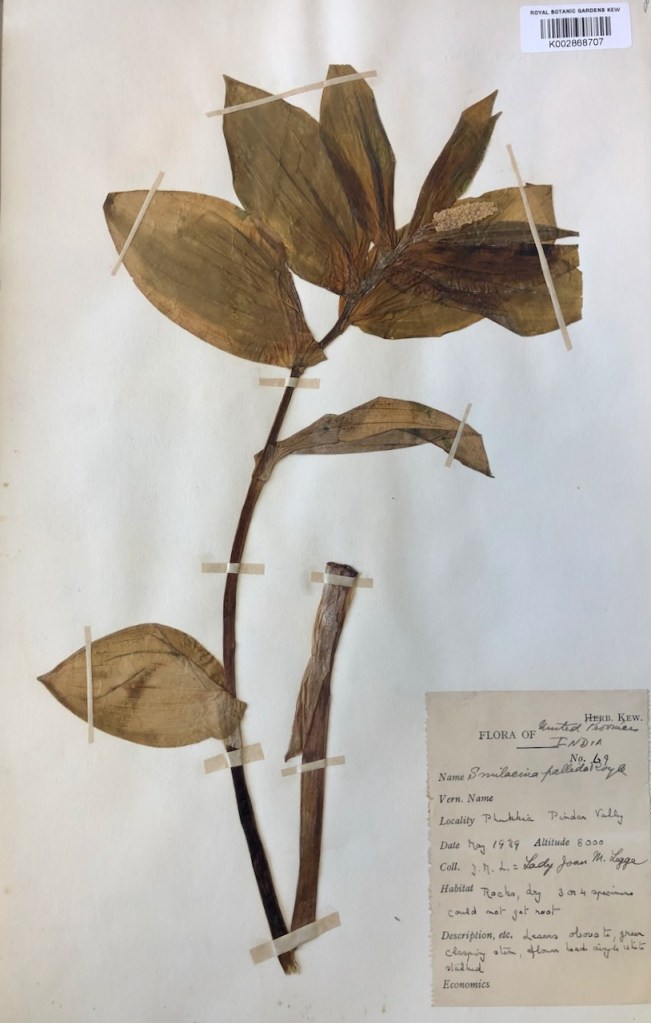

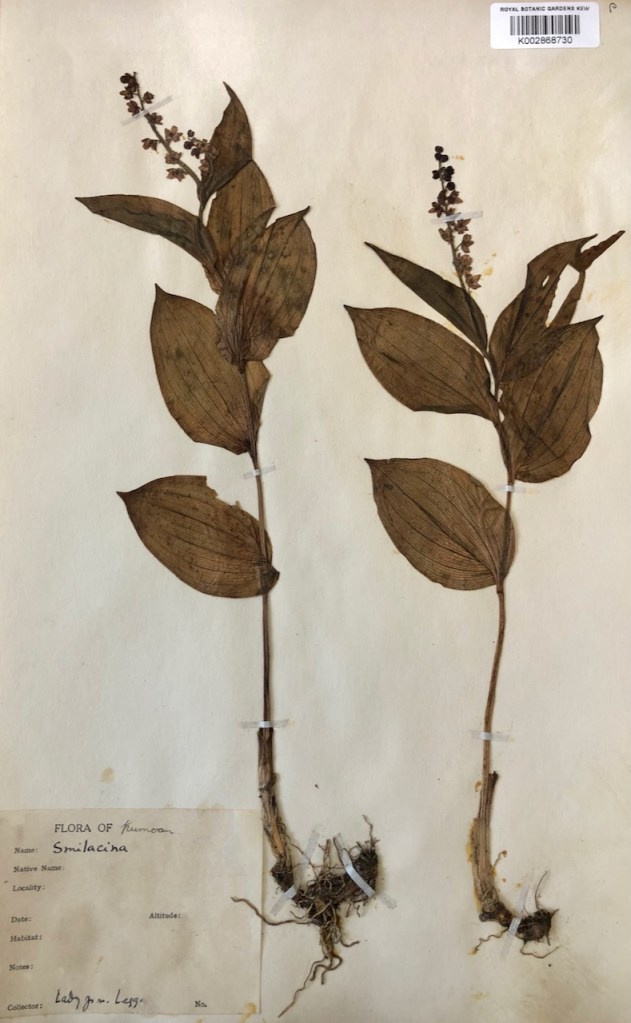

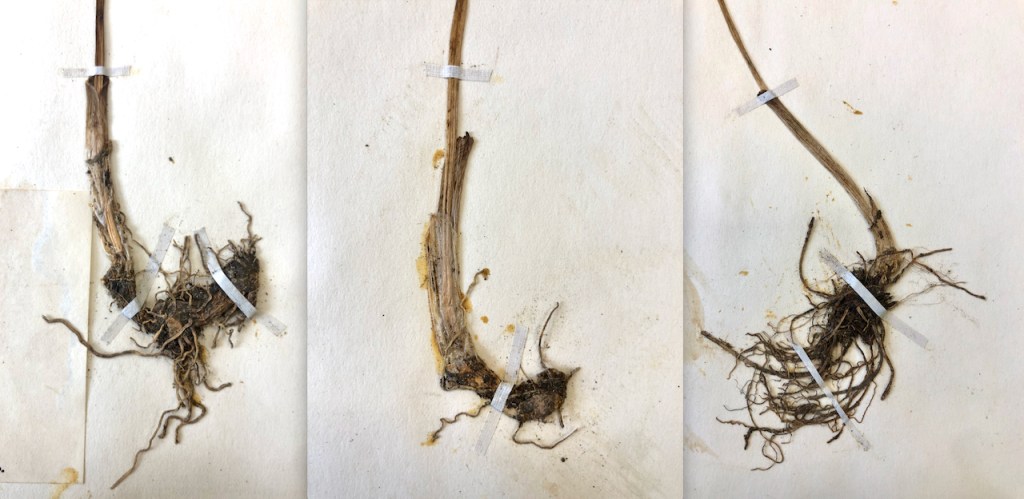

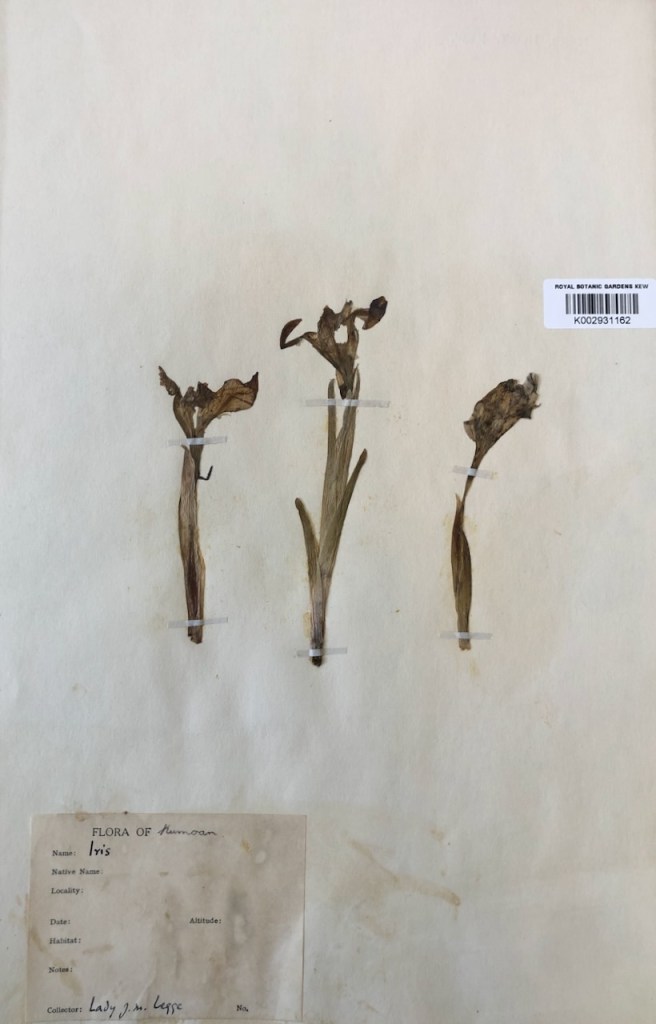

In the other, where those same workers drank tea, ghostly white plaster casts hang like three-dimensional botanical drawings reminiscent of the specimens Joan collected and sent to Kew Gardens.

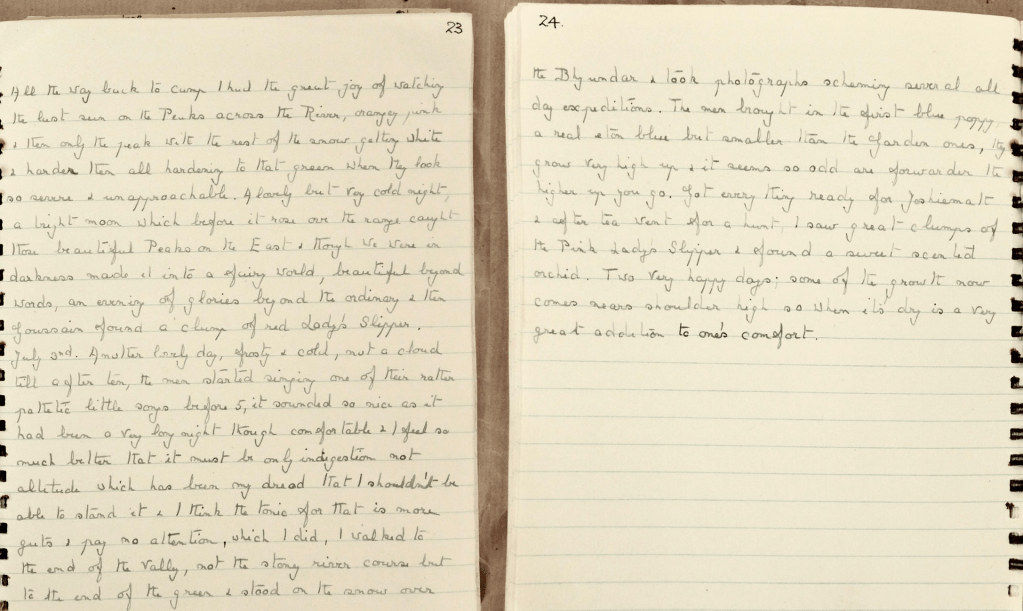

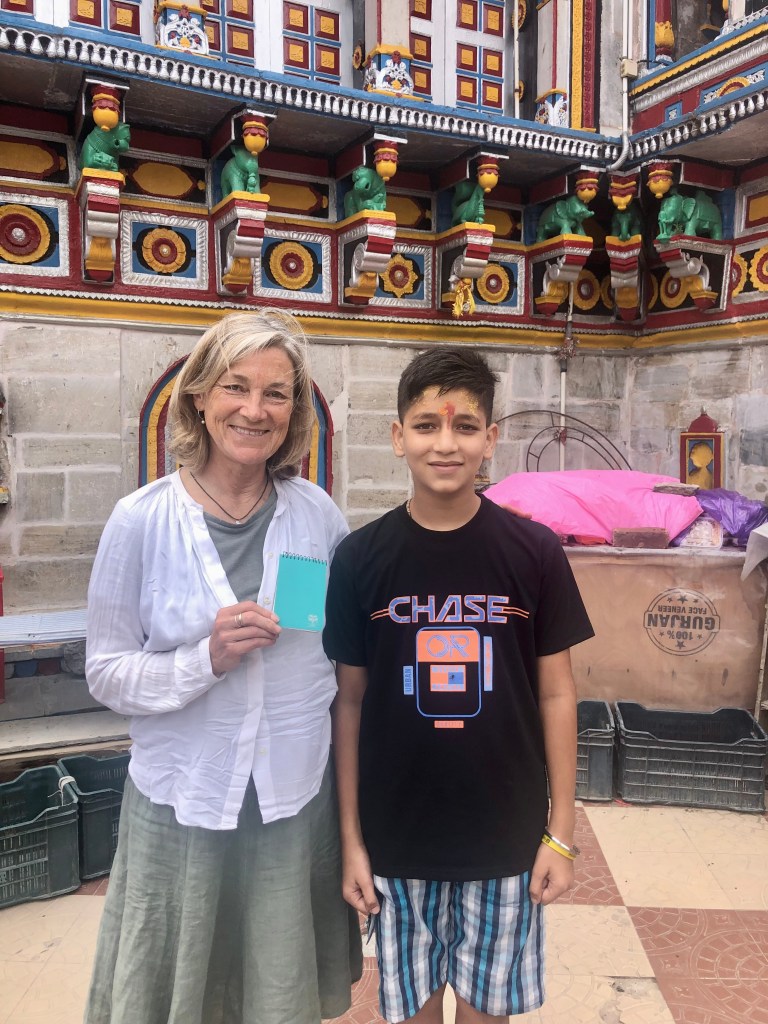

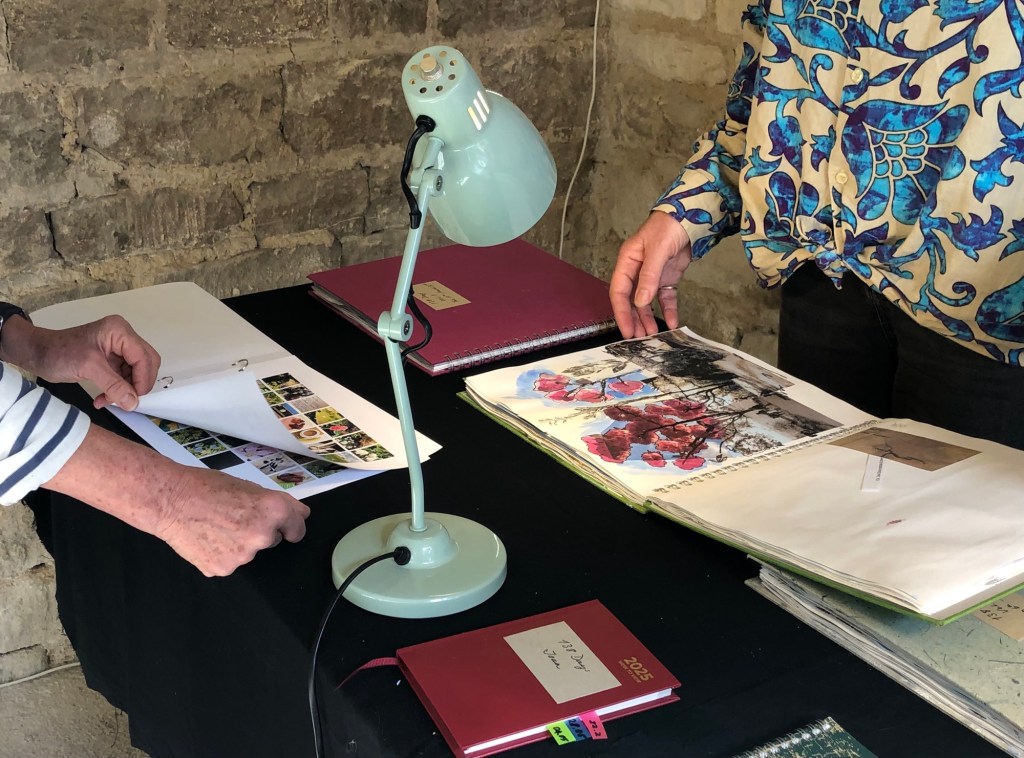

A series of square sketchbooks chart the 138 days I followed Joan’s 1939 diary entries. Starting on 17th February when I stepped into her shoes as she boarded a ship to India, I step out of them again on 4th July, the day she slipped off the edge of a Himalayan path to her death. One photograph, one sketchbook page, each day a quiet re-embodiment across time. Not a recreation of her journey, but a chance to listen more deeply to the changing tone of her voice in the final months of her life.

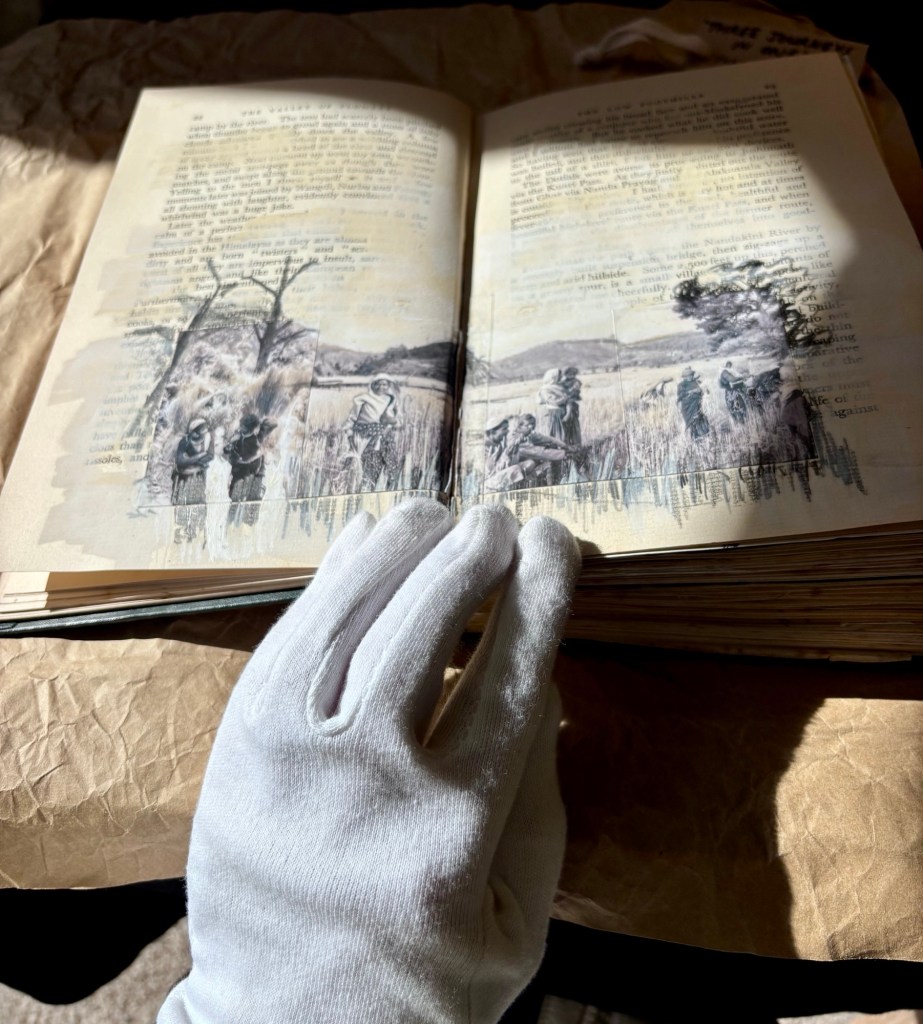

At the heart of the exhibition is its smallest piece: a re-working of a first edition of Frank Smythe’s Valley of Flowers, the very book that inspired Joan’s expedition. Through collage, drawings and pressed flowers, it now tells the stories of three visitors to the valley rather than just one: his, hers and mine. Wrapped in brown paper and tied with string like an archival package, the book invites visitors to wear white gloves to turn its delicate pages, not because it is precious in a monetary sense, but out of respect, Unlike most artworks, these ones are meant to be handled and engaged with.

There is nothing for sale. No press campaign. No sponsorship. Just a quiet space, tucked away in a garden, found by invitation or chance. A strange but deliberate choice, and to me, a more authentic reflection of the humbleness of where Joan’s life ended than any traditional gallery could offer.

What Joan lost in material possessions, she gained in purpose and joy. Her life distilled into what nine porters could carry. She found a sense of completeness long before she had completed her journey.

That’s what I hope to convey in the improvised, immersive pieces shown in the warm belly of my limestone vaults. People forgive imperfection and lack of polish as they connect with Joan’s story through their hands, senses and bodies.

Just as artists learn to see not just form but negative space – the shapes between things – so Joan’s outwardly abundant life transformed into an inner world: slower, quieter, less visible, but not lesser in any way.

Maybe this is a natural outcome of ageing… the gentle decluttering of ambition and a reshuffling of values. Or maybe Joan’s story is a simple reminder that richness cannot always be seen and meaning doesn’t always require an audience.

The symmetry in our shrinking trajectories is just an observation.

But it feels strangely right.

IN PROCESS…

Sunday 19th October, 11am-5pm and by appointment until 1st November.

The Vaults, 114 Bisley Road, Stroud