The past century has left heavy footprints all over the ever-changing face of Berlin. Without even scratching the surface, you can find the scars of murderous regimes, failed ideologies, war and destruction on all levels. But my regular visits to the city since 1990 have also witnessed the extraordinary resilience, creativity and defiant refusal to succumb to the particular ‘-ism’ trying to shape it. Throughout the city, past, present and future reside in a disturbing but reassuring harmony that promises not to forget, not to become complacent, not to allow such things to happen again while also offering plenty of opportunities for enjoyment.

Berlin’s contradictions are best experienced first hand. Feeling the city helps one to get closer to understanding it. It isn’t always comfortable, but it is infinitely interesting. Below is a little virtual / visual ‘tour’ of the two weeks I have just spent flâneuring through quarters of Berlin I hadn’t been to before, following my nose as I sniffed out history’s path into the present day. (You might like to read it on my Blog site, where the layout is more reliable.)

Striking in its lack of cosmetic disguise, evidence of the Second World War still lingers all too visibly: in the empty spaces left by bombed houses; the bullet holes from the final battle; and the enormous bunkers, now transformed into extraordinary galleries that house contemporary installations (Boros Sammlung) or offer an exquisite experience of Asian art in dark silence (Feuerle Sammlung).

After the war, the DDR evolved out of the Manifesto of the Communist Party of 1848 created by KARL MARX and FRIEDRICH ENGELS. Its goal was to ‘change the world’ and to this day, Karl Marx rates as one of the top three Germans, along with Konrad Adenauer (first chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany 1949-1966) and Martin Luther (Protestant Reformation).

The KARL-MARX-ALLEE, formerly Stalinallee, is the 90-metre wide, 1.2-mile long DDR boulevard lined by grandiose Moscow-style architecture built between 1952 and 1960 and scented lime trees. Designed to sing the praises of socialism, the buildings offered luxurious flats for workers as well as restaurants, shops and a still iconic Kino International cinema. Many of the apartment blocks were covered in ceramic tiles, earning the Allee the nickname of ‘Stalin’s Bathroom’. Half of them had fallen off by 1989.

In the oldest part of the city, a typical ‘Plattenbau’, the panel system-building made up of pre-fab concrete panels, some with basin and loo already attached, rises above a little-known but beautifully crafted frieze telling the history of communism and the DDR.

This year was the 70th anniversary of the 17. JUNE 1953 WORKERS UPRISING in protest against the state’s imposition of more working hours for no extra pay. It was crushed with Soviet tanks and troops leaving 123 people dead.

From 1961-1989, the BERLIN WALL effectively locked East Berliners into the regime’s paranoid ideology and ruthless regime. Monuments dotted on its snake-like course through the city tell the tragic stories of the more than 140 people who died trying to escape.

After the Fall of the Wall and the reunification of Germany in 1990, the next phase of (re-)building began and still continues everywhere. Some areas have been homogenised into the commercial cityscapes you can find the world over.

Around the Reichstag and central parliament area, ultra-modern architecture prevails. Outside Jakob Kaiser House, the all-important Grundgesetz or Basic Law is etched into glass – a fragile but resolute commitment by the Federal Constitution to guarantee fundamental rights in Germany .

Elsewhere, whole quarters have dodged development and been claimed by layers of graffiti and young hipsters with tattoos scribbled like doodles over their bodies. Political slogans and statements adorn buildings squatted in since ‘Die Wende,’ the peaceful revolution of the autumn of 1989 that led to East and West Germany and Berlin becoming one again: ‘Soldiers are murderers’. ‘Keep calm and don’t give a fuck’. ‘No God, no state, no patriarch.’

Then there’s swimming in the city centre or in one of the many lakes a cycle ride away; nude sunbathing in the parks and the chatter of endless cafés and bars that spill onto the streets.

Nestled between new and old, the constant reminders of what Germans – and the world – must never forget…

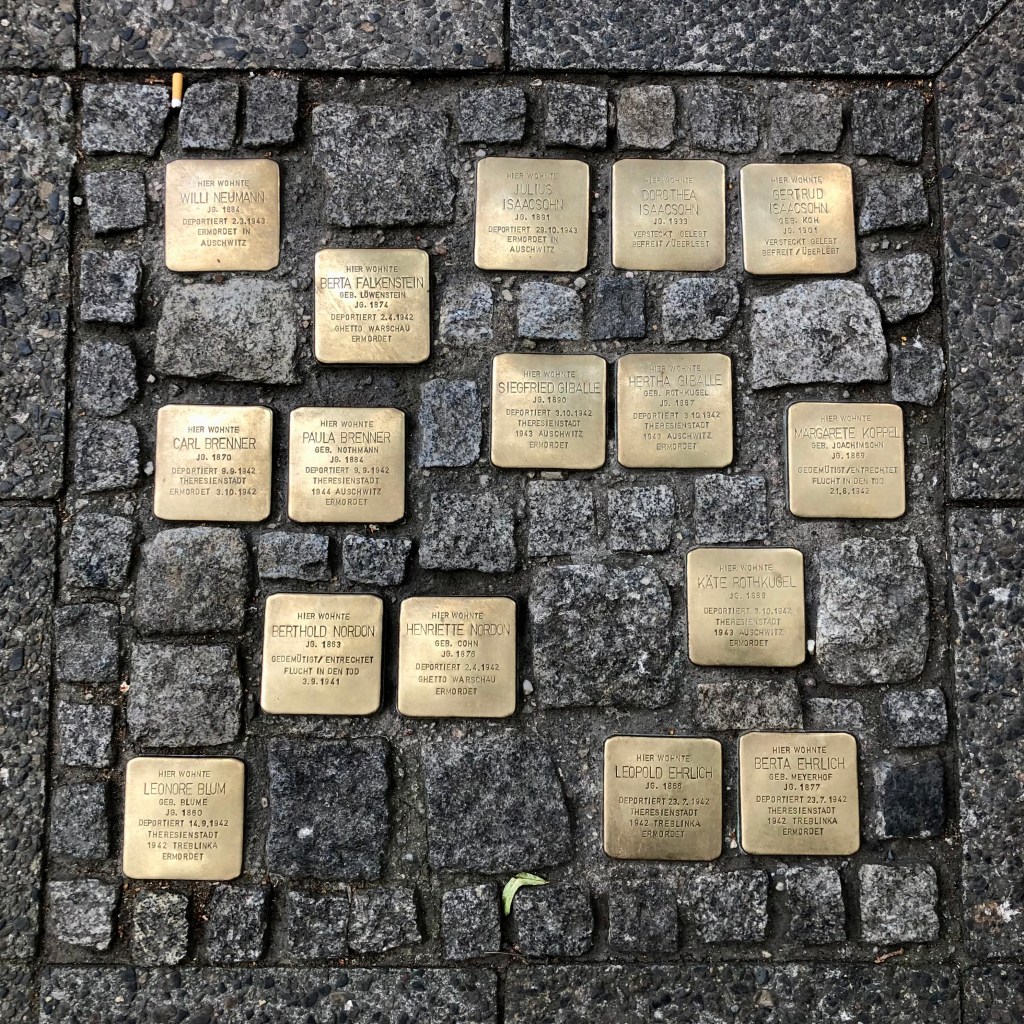

Stolpersteine – stumbling stones – glisten from the pavements naming and remembering those who once lived in these streets before they were deported and murdered by the Nazis.

And in the very heart of Berlin, right between the Reichstag and the Brandenburg Gate, against a soundscape of raindrops and a quiet recording of single violin, I witnessed the daily laying of a fresh flower on the triangular island in the middle of the pond that is the Memorial to the Sinti and Roma Victims of National Socialism.

Berlin exudes a wealth of experience and suffering mined from the psychological, moral, philosophical and political depths into which it has plummeted time and again. But it feels to me and many others who love being there, that out of all the conflicting and restricting -isms of the past century, the power of the individual now has its rightful place. Be yourself, the city seems to say. You won’t be judged here.

Long may that last…