For more than 30 years I have been watching cranes and diggers deconstruct and rebuild the architectural face of Berlin. It is an infinitely fascinating process to follow.

The focus of my most recent trip, however, ended up being the people who inhabit the city, both past and present. And typically for Berlin, it has created a brilliant exhibition to trace the changing faces of those who lived through its turbulent history.

Enthüllt / Unveiled is housed in the Renaissance Citadel in the western borough of Spandau and not only offers a surreal experience but also an inspired response to the emotionally and politically charged ‘statue debate’.

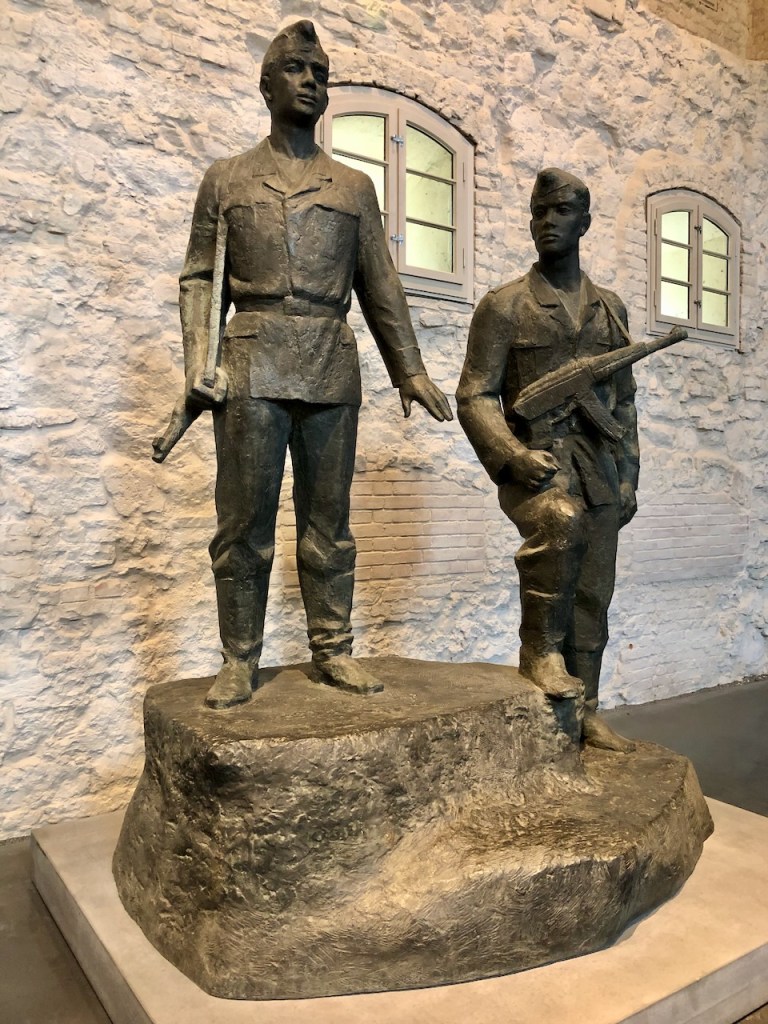

Housed in the 114-meter-long former Provisions Depot of the fortress, Berlin’s once revered or feared rulers, Prussian military heroes and bishops rub marble and bronze shoulders with thinkers, revolutionaries and victims. Spanning a timeline from the 12th century Albrecht the Bear (whose face you learn would not have been known so would have been crafted from a local tradesman or friend of the sculptor’s) to contentious GDR border guards, most of the statues have been removed from their plinths to stand at eye level. Many are missing limbs and noses or even their entire bodies. With chests still puffed but their status removed, you meet the figures of history on equal terms. It is a powerful experience.

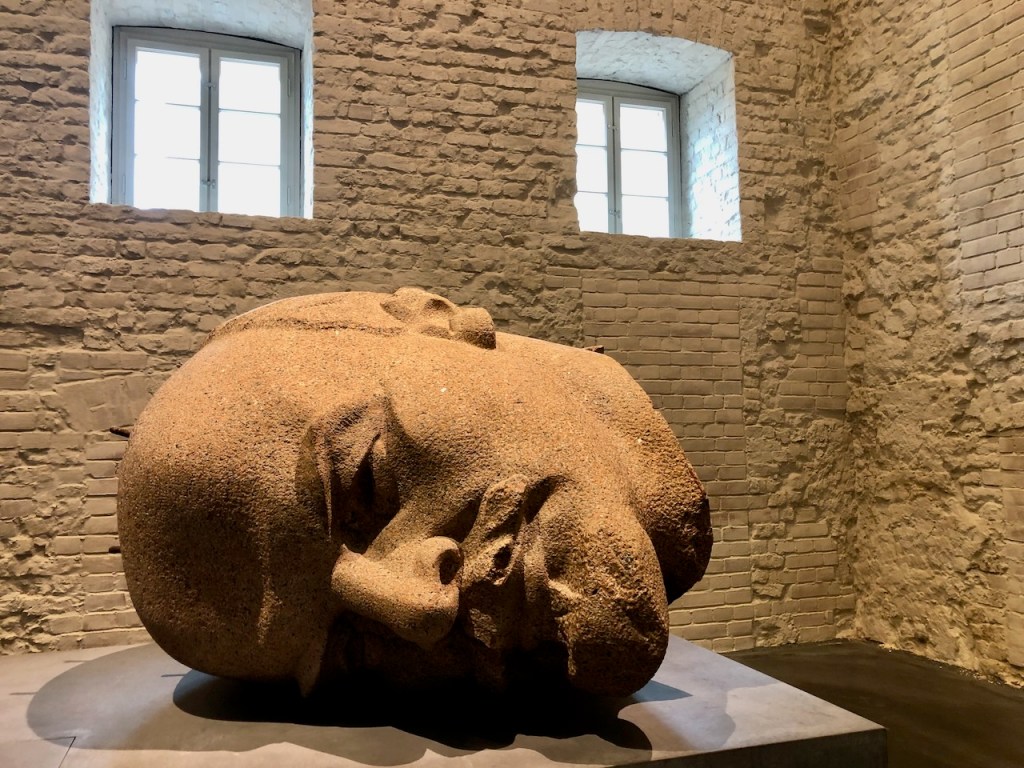

One of the highlights of the exhibition comes right at the end. Displayed on its side, Lenin’s 3.5-tonne granite head once rested atop a 19-meter-high statue by Soviet Sculptor, Nikolai Tomski. Created in 1970 and designed to blend with the Soviet architecture around Lenin Square (now United Nations Square), it was pulled down in 1992, cut into more than 120 blocks, buried in the Müggelheimer Forest and covered with gravel. It was recovered in 2015 for the Citadel exhibition, complete with nibbled ears (people chiselled off chunks for souvenirs) and transportation bolts sticking out of the crown.

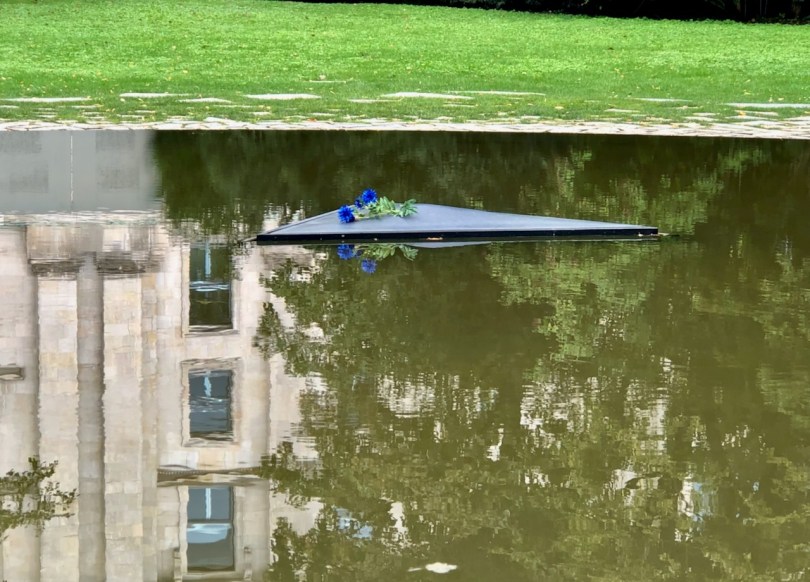

Traditional memorials are generally markers of achievement and greatness. Raised on plinths, you ‘look up’ to the person or event being celebrated. But what happens when they no longer reflect the values of the time, when their legacy becomes toxic? Do you leave them as lifeless witnesses to a time past with no apparent power in the present? Do you topple or remove them in an attempt to lose the history, or does that lose the discourse and potential to learn lessons? Do you contextualise them with plaques…?

Germany, with its contentious past has explored these questions possibly more than anywhere else. Accompanied by huge debate, emotion and financial investment, statues and monuments have been removed, banned, dismantled, buried, unburied, re-erected in new locations, built from scratch… All this can be read about in the ubiquitous digital documentation running through the exhibition. But Dr Urte Evert, the curator of Unveiled, seems to have done something very clever. By allowing visitors to touch the statues, children to clamber on them, artists to respond to them, performers to dance among them, she encourages engagement and dialogue, not only with the art forms, but with history. And this feels more important today than ever.

What is also striking, but not surprising, is that every statue from Kaiser Wilhelm I to Alexander von Humboldt and Immanuel Kant is a man. Apart from one, Queen Luise, wife of King Friedrich Wilhelm III and an early form of celebrity referred to as the Queen of Hearts… or according to Napoleon “the only real man in Prussia.” Even in today’s Berlin there are few statues celebrating women and even fewer to individual women.

In a square named after her in the fashionable district of Prenzlauerberg, a rather lumpy and grumpy-looking Käthe Kollwitz, artist, sculptor, committed socialist and pacifist sits on a heavy block narrowly dodging graffiti. She is remembered everywhere and this is just one of many statues of her.

Originally placed on a hill made of the bombed remnants of the city but now reposing with hammer still in hand in the greenery of Hasenheide Park, a Memorial to the Trümmerfrauen of Berlin offers acknowledgement to the ‘rubble women’ who cleared and sorted Germany’s destroyed cities by hand, stone by stone.

More centrally and on the site of the destroyed Old Synagogue, the Rosenstraße Monument, also known as the Block of Women, marks the 1943 peaceful uprising of some 600 non-Jewish German women who demanded the SS and Gestapo release their detained Jewish husbands awaiting deportation. It was a rare moment of successful protest against the Nazis.

And Rosa Luxemburg, one of the founders and heroines of the anti-war Spartacus League is remembered in big letters spelling out her name along the side of the Landwehr Canal where her tortured and executed body was fished out in 1919. She also has a figurative statue outside the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung in Friedrichshain.

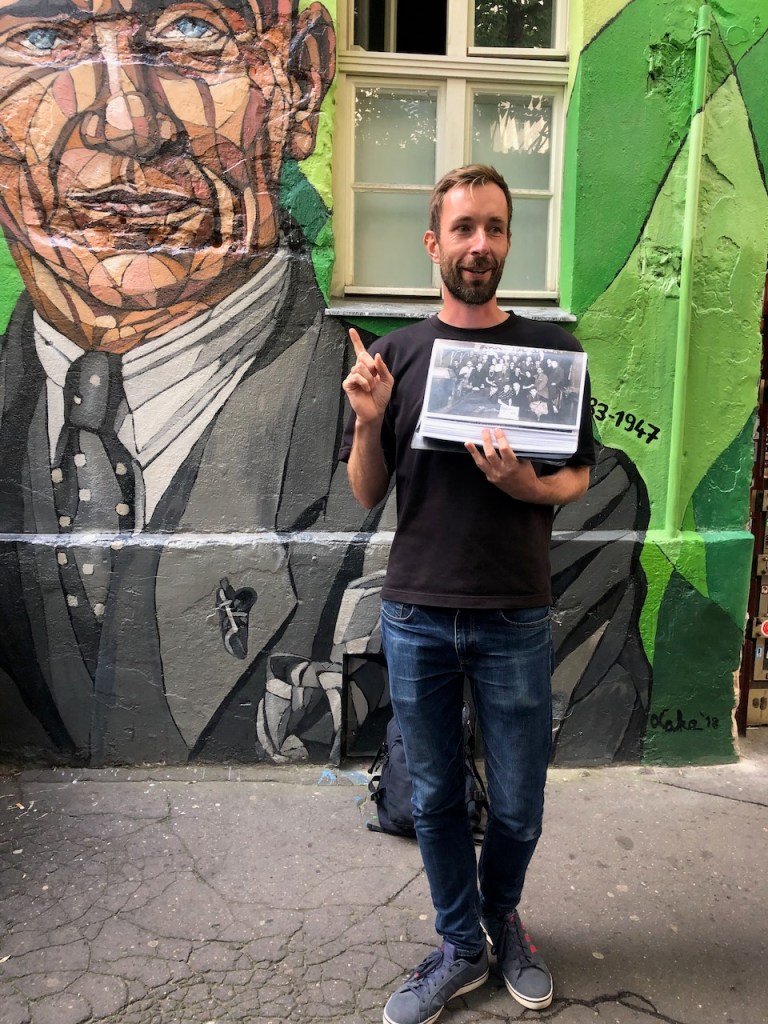

There are no doubt more but today the demographics of Berlin look very different. It’s a cool international city of young hipsters, artists, entrepreneurs, thinkers, activists, expellees, refugees, LGBTQ people, politicians, former GDR bureaucrats and prisoners… the list is long and colourful. John Kampner’s excellent book In Search of Berlin charts its development over the centuries, its ruptures, reinventions and constant search for identity. I keep thinking I know Berlin quite well now, that I have seen a lot of it… how wrong I am. There is more… so much more. And a highlight of this trip was joining Matti Geyer of Tours of Berlin on one of his private tours. (I love a good walking tour and have been on many.) As a born-and-bred Berliner with incredible knowledge and delightful delivery, he could bring new corners of the city to life and introduce me to further gems in this ever-transitioning city. I am already look forward to accompanying him on another.

Germany’s relationship to its past and Berlin’s unique relationship with itself have been fraught with challenges. But while you can feel the unsettled rumble of discontent that has spread throughout Europe and beyond, the wounds and divisions appear to be healing. There is an effortless confidence in its integration of past shadows into its present identity which none of the shiny new façades can hide.

Further reading (as always not necessarily reflective of my views):

Aryan homoeroticism and Lenin’s head: the museum showcasing Berlin’s unwanted statues by John Kapner, The Guardian

History set in stone by Penny Croucher

In Search of Berlin by John Kampner

Counter Monuments: Questions of Definition by Memory and History Blog