This Remembrance weekend has been receiving more publicity than most years. As I write, at 11am on 11.11. hundreds of thousands of people are gathering in London, not to observe the traditional one-minute silence, though many I am sure will, but to march in support of Palestine. Not far from the Cenotaph, police are clashing with far-right protestors chanting “England ‘til I die”.

I don’t want to get into the heated debates that have criticised or defended the timing and legitimacy of these marches. But, being a blogger about (among other things) the importance of remembering the past, I would like to take a step back from the specifics to soft-focus on the significance of Remembrance Day and in particular on the often heartfelt, sometimes platitudinous mantra of ‘Never Again.’

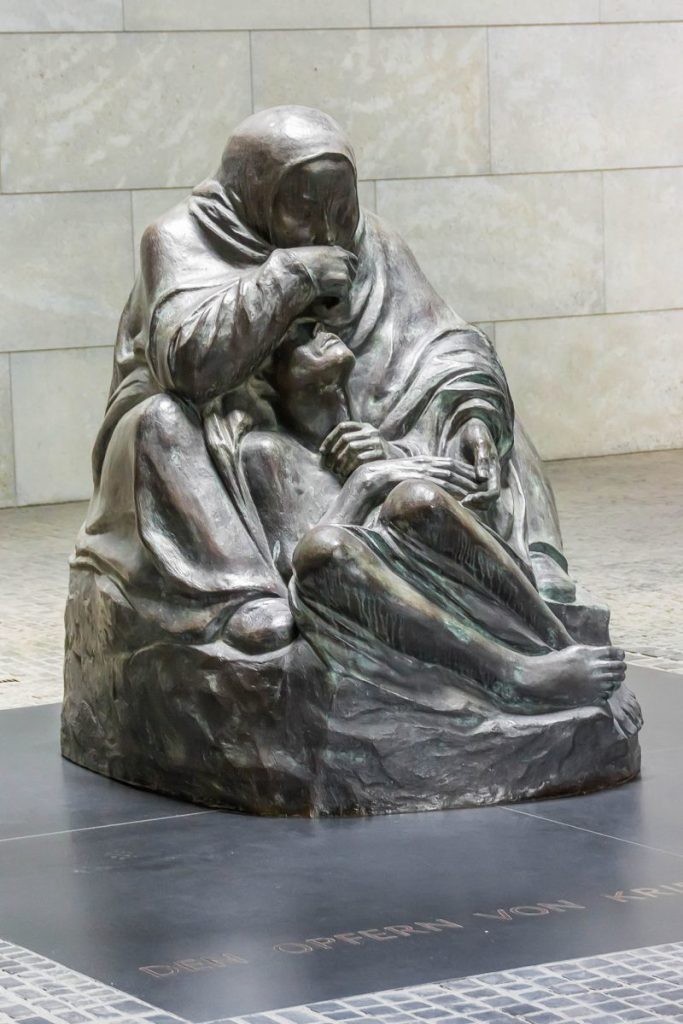

What do we mean when we say ‘Never Again’? The original ‘Nie Wieder’ slogan appeared in post-war Germany and the words are usually used in association with the Holocaust and other genocides. In Berlin on 9th November, to mark the 85th anniversary of the 1938 November pogroms widely known as Kristallnacht, the words ‘Nie Wieder ist jetzt’ – ‘Never again is now’ – were beamed onto Berlin’s Brandenburg Gates. An all too timely reminder as since the Hamas attacks on Israelis on 7th October, antisemitism has been on the rise. Not just in Germany, but globally.

‘Never again’ is of course a passionate, urgent and vital reminder to never allow anything like the Holocaust to happen again. I end all my talks on Germany’s culture of apology and atonement with exactly that call. And for younger generations, I add Michael Rosen’s warning about fascism:

“I sometimes fear that people think that fascism arrives in fancy dress worn by grotesques and monsters as played out in endless re-runs of the Nazis. Fascism arrives as your friend. It will restore your honour, make you feel proud, protect your house, give you a job, clean up the neighbourhood, remind you of how great you once were, clear out the venal and the corrupt, remove anything you feel is unlike you…”

Both are a call to each one of us to be awake and to take responsibility. But what meaning can Never Again have for those of us who like to think we are not particularly susceptible to or guilty of antisemitism or discrimination anyway? (A huge debate in itself, but not for right now)

Last month, after talking with a Jewish friend about the dilemma of not knowing what to think, feel or do in the wake of the desperate situation, she sent me a draft of an essay she was working on. In it she broadened out the Never Again message to include all humanity: “The ‘task’ of the Holocaust has come out of the shadows and into the foreground with blistering clarity in recent weeks – and if the foundation of this task is to honour the pledge ‘never again’, this pledge must apply to all humanity. It is not exclusive to the Jewish people; to transfer the trauma of one population on to another is no victory.” (The full version Beyond Binaries by Miranda Gold will be available soon.)

Much has been written about this. Indeed, I discuss it in In My Grandfather’s Shadow at the end of Chapter 22, ‘Lest we forget’. But recently I have discovered another level of instruction in those two words. It asks us not to other ‘others’ on any level. Because that is when the seeds of barbarity and atrocity are sown.

Most of my work is dedicated to trying to see and understand the ‘other side’ of a story. It is one of the things for which I am grateful to my dual-nationality. Scorsese’s latest film Killers of the Flower Moon, however, highlighted where I was failing. Starring Robert De Niro, Leonardo DiCaprio and Lily Gladstone, all brilliant in their roles, it depicts the deception and murderous treatment of the Osage Native Americans in the 1920s by white settlers after their oil rights.

I hated the film. So much so that I fell asleep! I now see that I literally couldn’t take any more of what I would afterwards clumsily call ‘white man’ violence and cruelty. I basically dissociated – a common trauma response. Of course it is not only white men who are violent and cruel. Nor is it all men. But in that moment, on the back of an intense schedule of talks about prisoners (96% of which are men), Nazis, WW2, Britain’s colonial past etc. etc. and against the backdrop of Hamas’s heinous attacks, Israel’s deadly retaliation and the disturbing revelations of the Covid enquiry to name a few – I had identified with the victims of these historical male-dominated actions. The attitudes within the film scratched my own childhood wounds of being shamed and othered as ‘German’ (at the time completely synonymous with Nazi) and tipped me into complete overwhelm and overload. The dense darkness of psychic saturation had nowhere to go other than through what felt like a primeval roar.

I have no doubt that many people, maybe you too, have at times felt something similar.

A couple of uncomfortable encounters over the next few days in which one person raged and another decidedly disengaged made me realise that my response to some highly generalised image of ‘man’ was no way to proceed. I could feel myself slipping into a form of oppositional camp, taking a side, seeking the solidarity of a “team”, as Biden unhelpfully phrased it recently. For in that moment, I was doing exactly what I personally feel the call for ‘Never again’ is asking us not to do. I was creating a binary division between myself and those I saw as doing or being responsible for ‘wrong.’ I blamed ‘them’, while licking the wounds of a collective (female) ‘us’. Statistically and historically some of this ‘male’/’female’ categorisation has a degree of reality and validity, but it is not the way forward.

It is in othering that we can justify discrimination and violence.

It is in othering that we can harm and be harmed.

It is in othering that we all become capable of failing to uphold humanity’s plea for ‘Never again’.

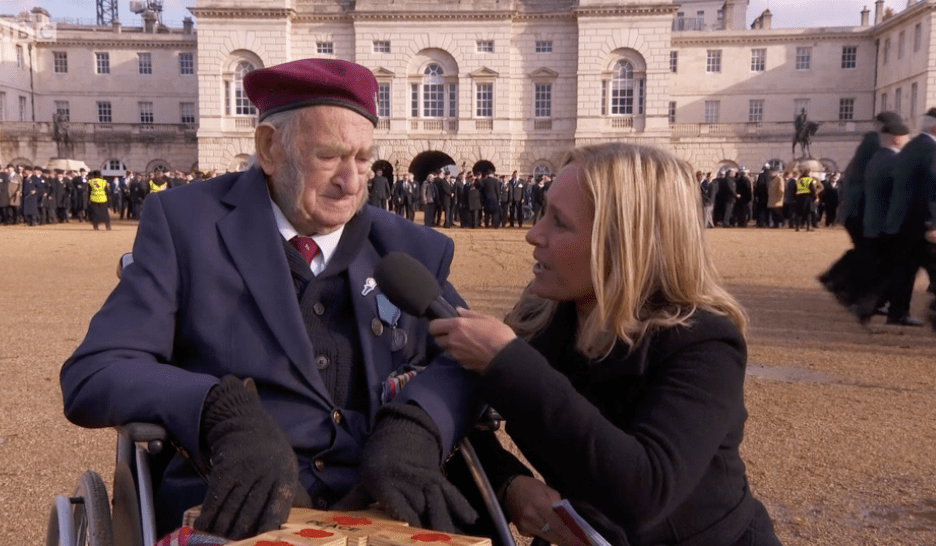

So, for me, this Remembrance Sunday is not only a day to honour the memories of our own fallen who served, defended and died, and to renew an annual pledge to peace in the world that clearly isn’t working. It is an occasion to also extend our thoughts way beyond our own shores to all people who have died and are dying in conflicts and wars. And to reach deep into our hearts to help heal the divisions that are leading to discrimination and violence in every land. By searching hard for the fellow human being in all perceived enemies and all those we vehemently disagree with, no matter how hard that is; by finding the place that lies somewhere between the external roar of internal rage and the deadening desire to turn away and disengage, we can remain in our hearts. We can keep sight of our innate oneness. That, to me, at least makes some sense in a world that increasingly doesn’t make any.

Further Reading

Never again is now’: 1938 Nazi pogrom anniversary marked in Germany by Kate Connolly

Hollywood doesn’t change overnight: Indigenous viewers on Killers of the Flower Moon