Friday 8thMay 2020 will be the 75thAnniversary of the end of the Second World War in Europe. It was the day when millions of people took to the streets and pubs to celebrate. For those who can remember that time in 1945, the emotions will be particularly poignant. Victory over the German enemy finally brought the promise of peace. That is indeed worthy of celebration. But what should we be doing three quarters of a century on?

On Saturday 2nd May, I was due to be in Belluno on the edge of the Dolomites standing together with a group of total strangers from America and Italy. We had connected on Facebook and had hatched a plan to meet in the area where seventy-five years previously our fathers’, or grandfathers’, paths had crossed, first in war and then in peace. My sister, mother and my two octogenarian German aunts were coming too.

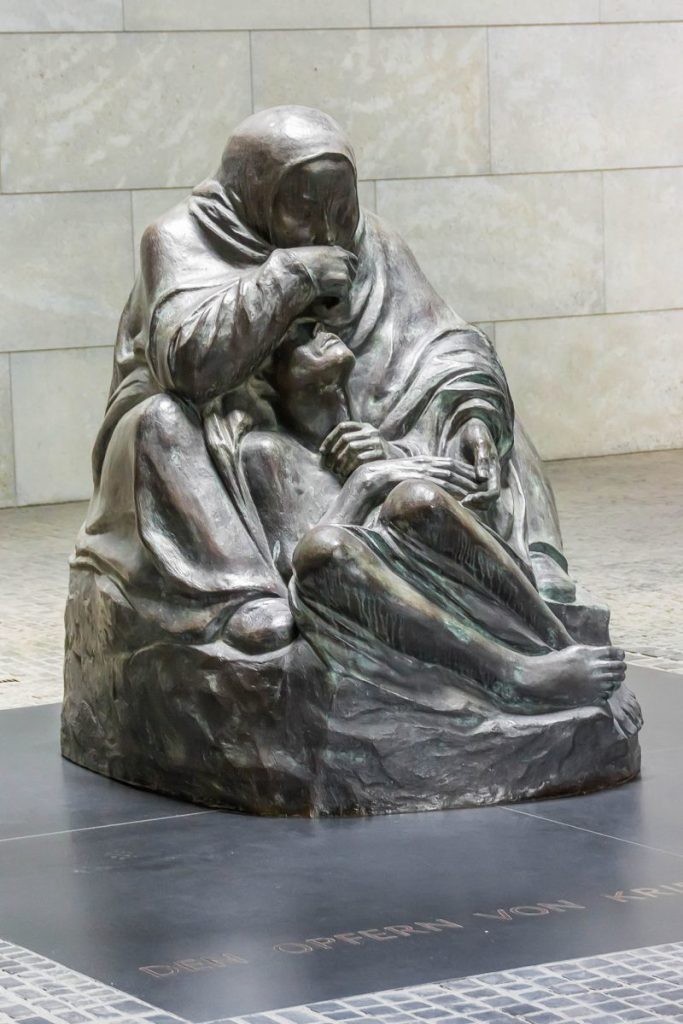

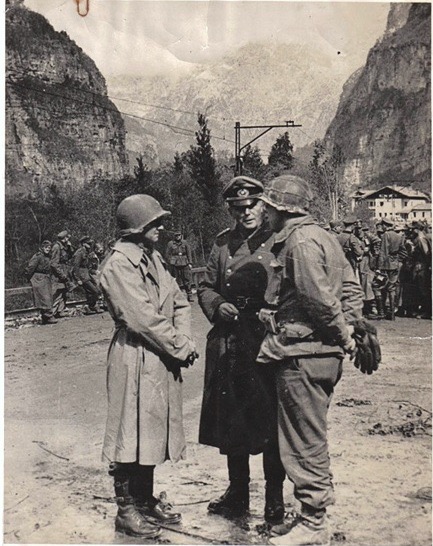

For me, it had all started fifteen years ago with the discovery of a photograph. I had googled my German grandfather’s name for the first time and the small black and white image that appeared on the screen instantly commanded my full attention. Until then, I had only known my grandfather as a framed photo on my mother’s writing desk. Just a face slightly obscured by the peak of a General’s hat with an iron cross hanging like a choker from a collared neck. He hadn’t moved in forty years. Now he was suddenly standing in front of me, wrapped in a belted, three-quarter length coat trimmed with a double row of perfectly aligned shiny buttons.

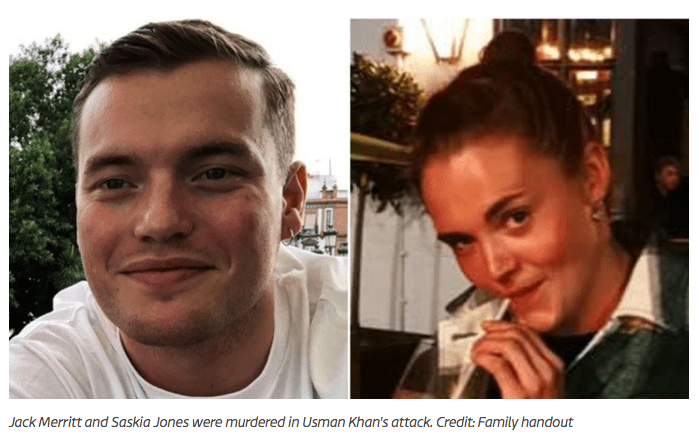

His face is instantly recognisable, his eyes still partially hidden as he talks to two men in baggier uniforms. He looks relaxed, upright. There’s even an air of authority in the way one of the seventy-a-day cigarettes I had often heard about rests between the fingers of his right hand. Reading the caption below the photo, I learn that it is 2nd May, 1945. The soldier on the left is an American Colonel, CO of the 337thInfantry, the other a translator. They are negotiating the handover of German troops and armaments. This is the day of Germany’s unconditional capitulation to the Allies. The moment my grandfather’s war ended and his time as a prisoner began. His experiences in the years that followed as a POW to the British would shape his family’s inner, and outer, worlds.

After years spent disentangling the family roots from the blood-soaked mud of conflict and Germany’s post-war silence, my relatives and I would be travelling to meet the sons of the American 337th Division and the granddaughter of the Colonel in the photograph. They had warmly welcomed me into their group. This 75thanniversary, supported by the Councillor of Culture in Belluno, had little to do with victory or defeat, winners or losers, goodies or baddies. It was about reconciliation. About growing friendships and understanding in the soil of broken grief and lingering pride or devastation. It promised to be a very special occasion… we will try again next year.

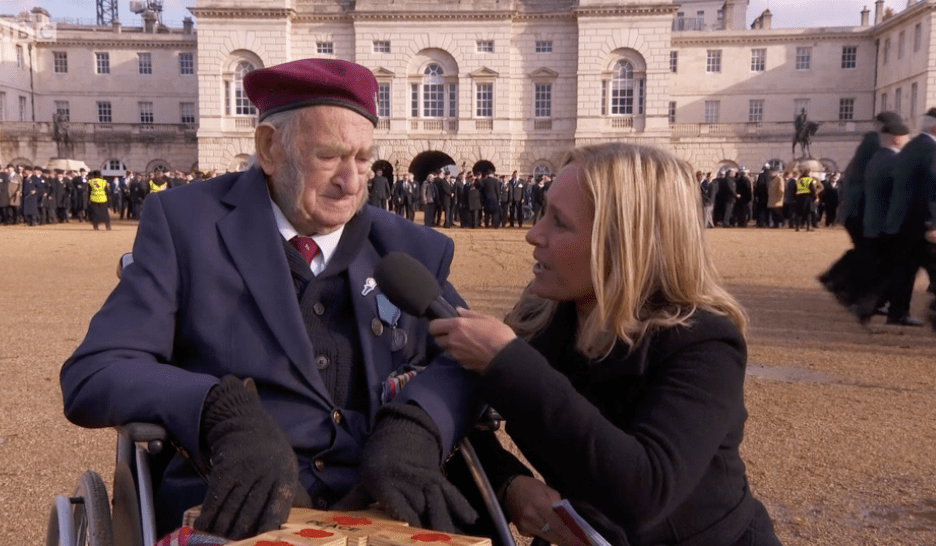

I can feel I am slightly bracing myself for what will happen on 8thMay. How will Britain mark this historic occasion? Energetic flag-waving aside, will it be much the same as our annual Remembrance Days in November and D-Days in June? Tony Hall, Director General of the BBC says their coverage “will bring households together to remember the past, pay tribute to the Second World War generation, and honour the heroes both then and now.” So yes, judging by that and the day’s schedule, it probably will.

Starting with a two-minute silence at 11am, a series of sing-alongs, prayers and encounters with veterans will follow, all interwoven with the familiar black and white footage. Then comes an evening of singers and actors performing well-loved songs, poetry and stories until 9pm when the Queen’s pre-recorded message will be broadcasted to close the day. Those who have got this far will probably feel slightly mushy (and possibly quite drunk). Filled with genuine gratitude to those who served, they will feel proud to be British, to be on the side of the victors and the heroic defenders of our freedoms… And that is all fine. Of course it is. But it’s not enough anymore.

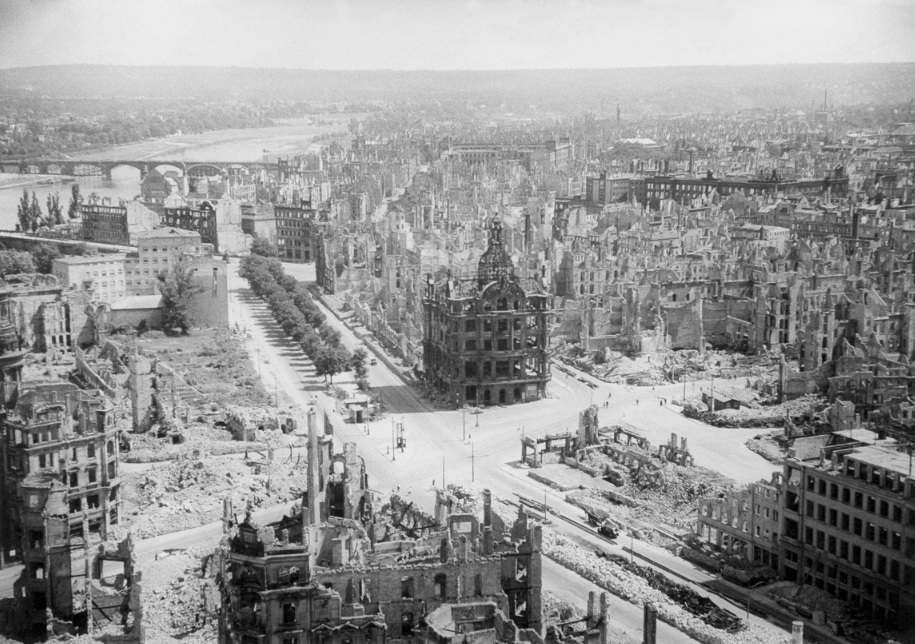

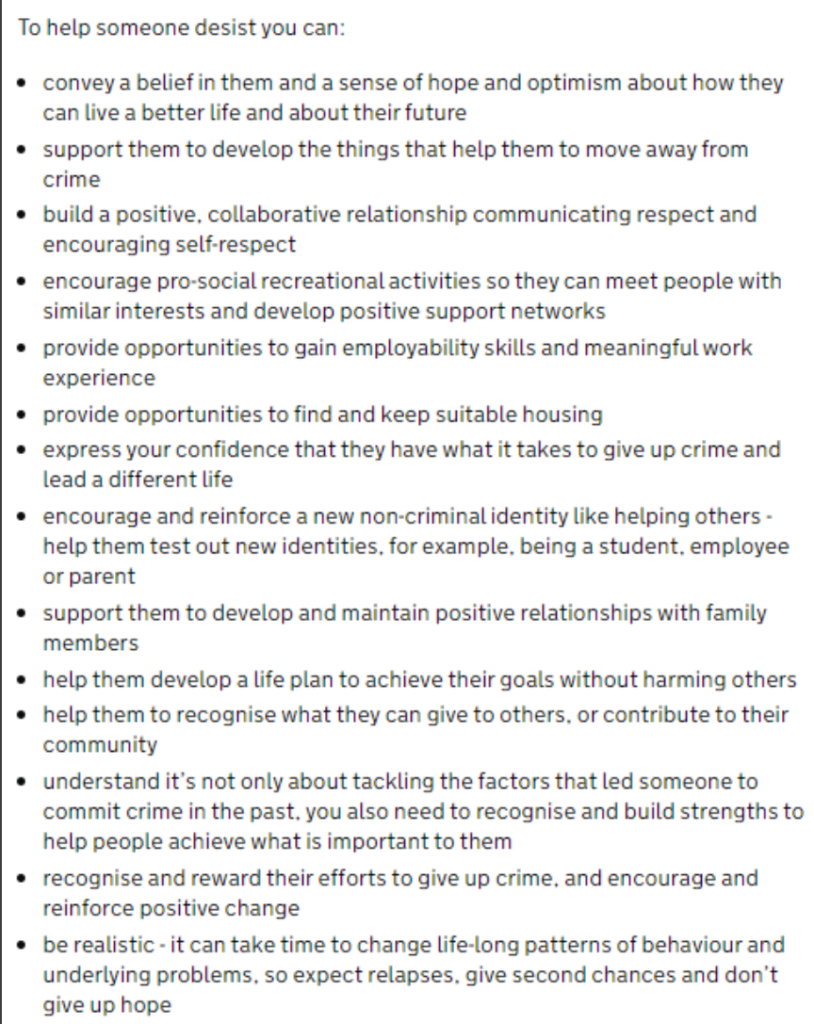

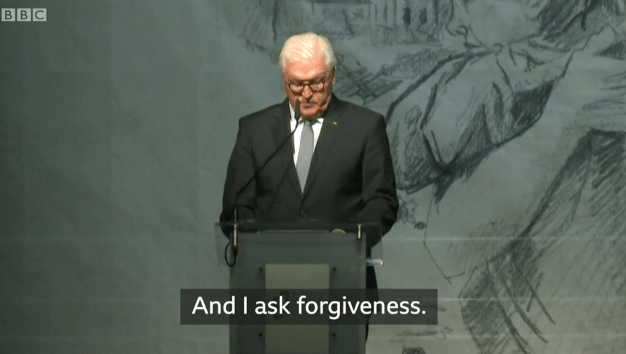

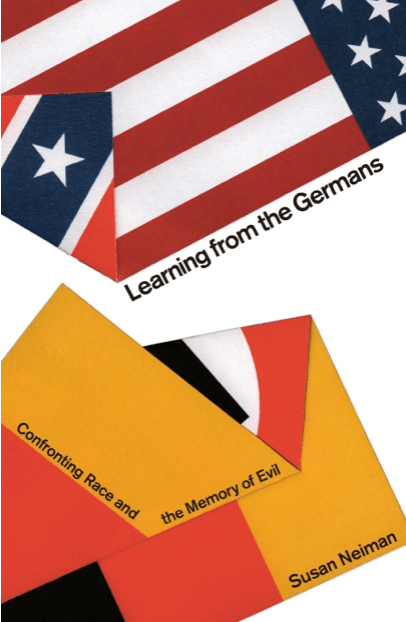

History used to be a matter of consolation or pride, now it is more a matter of warning and learning. As it shifts over time, black and white narratives of good and bad, victory and defeat, perpetrators, victims and heroes no longer hold. The story becomes more nuanced, the divisions more blurred, the lessons more universal. Simply remembering has become empty. Yet as Susan Neiman explains in her excellent book, Learning from the Germans, “We are not hardwired for nuance. Learning to live with ambivalence and to recognise nuance may be the hardest part of growing up.” No country can fully celebrate the triumphs of its history while ignoring the darker moments. So we cannot, nor should we be allowed to rest in our national self-image as the incontestable good guys. Seventy-five years ago, yes, but not today.

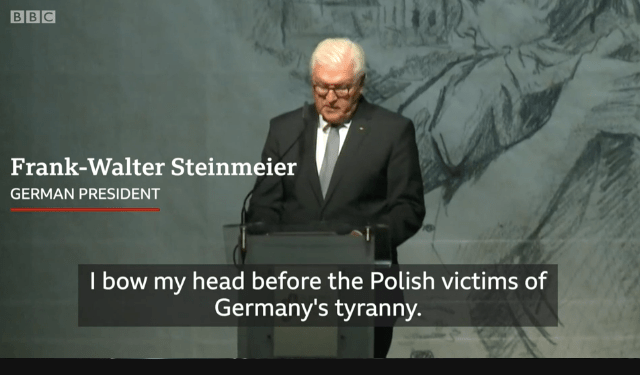

Neil Macgregor, former director of the British Museum and now of the Humboldt Forum in Berlin notes: “What is very remarkable about German history as a whole is that the Germans use their history to think about the future, where the British tend to use their history to comfort themselves.”

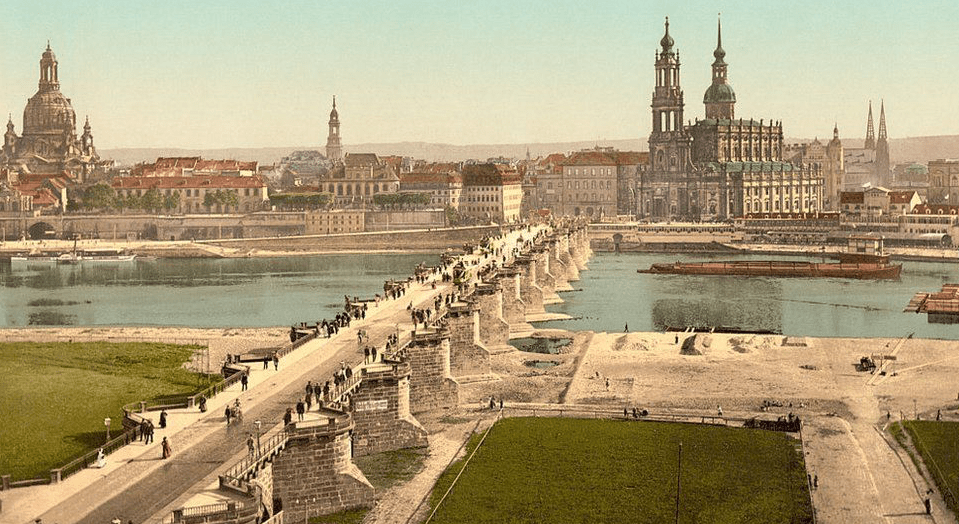

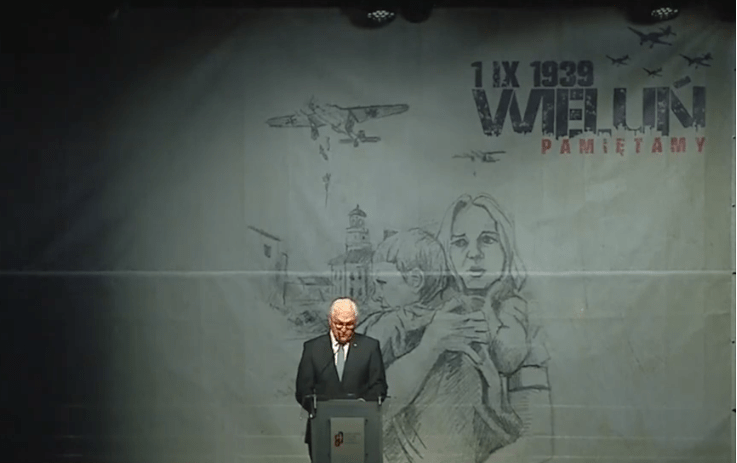

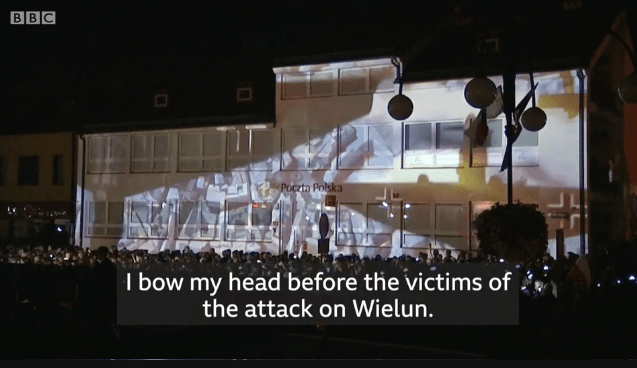

Maybe 75 years on is the right time for us to stop merely re-playing the gore, glory and gratitude of the Second World War and to start reaching beyond our own borders to include the histories and destinies of foreign populations, such as Russia, Poland, China – even Germany, who lost infinitely more and triumphed daily in tinier, but no less important ways. With a general consensus among historians about what happened and why, we can then shift our emphasis onto becoming fully aware that no country is immune from falling into the same abyss as Germany. Its descent happened gradually in full view. Like a frog being slowly brought to boil in a saucepan, most people didn’t notice.

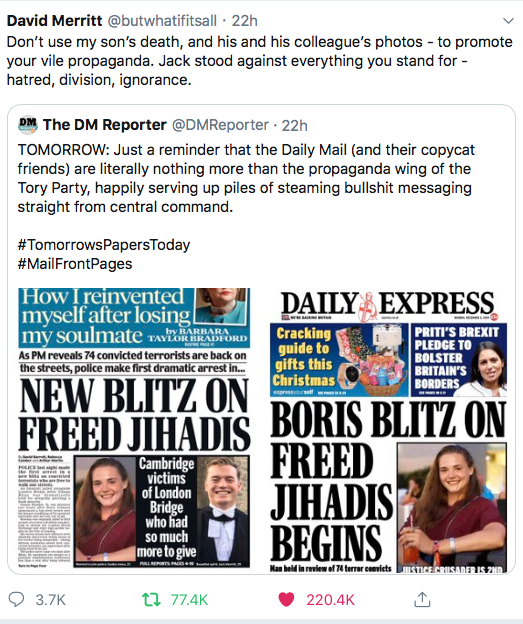

Covid-19 has ushered in a rash of startlingly rapid changes to our laws and freedoms. We are forcibly and necessarily being shaken out of complacency and into the realisation that civilisation as we know it is both fragile and reversible. So more urgently than ever, our World War anniversaries need to be reminders of this and opportunities for learning and growth to inspire collective vigilance against darker forces and a genuine sense of unity across borders.

Let’s see what happens on Friday. If I wave anything, it won’t be a flag for Victory but a white flower for on-going Peace.

Some other views I found interesting: