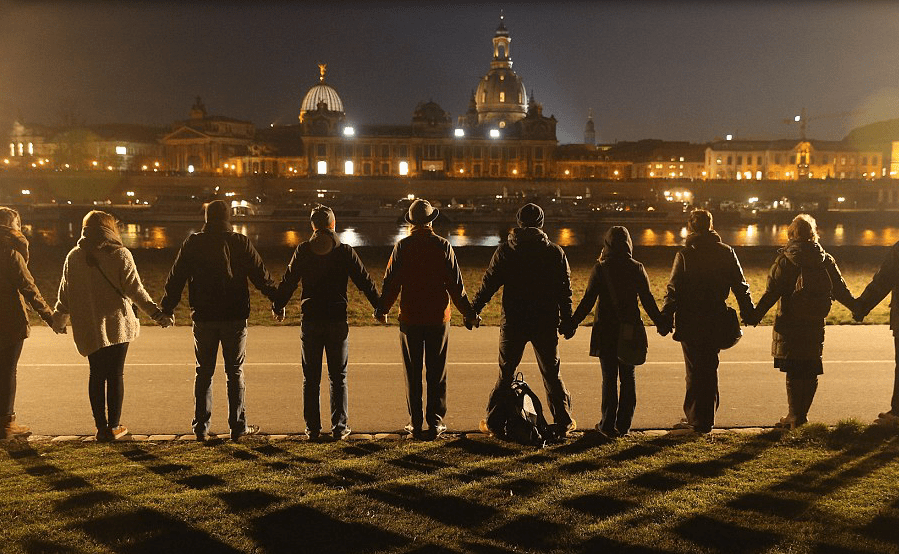

From 13th-15th February, Dresdeners will be gathering to mark the anniversary of the destruction of their city in 1945. This year, rather than creating their usual human chain to snake through the city in peaceful reflection, it will, like most things in this pandemic, be a largely online affair. A Dresden Trust trustee always attends the event as a gesture of deeply-felt solidarity and reconciliation. This year was to be my year to represent the Trust, but instead we have sent a video of messages to our friends and contacts there. Immediate emails of thanks reveal how deeply moved they have been by this extension of virtual British hands and hearts to them. It was a tiny act on our part, but its value was clearly of significance.

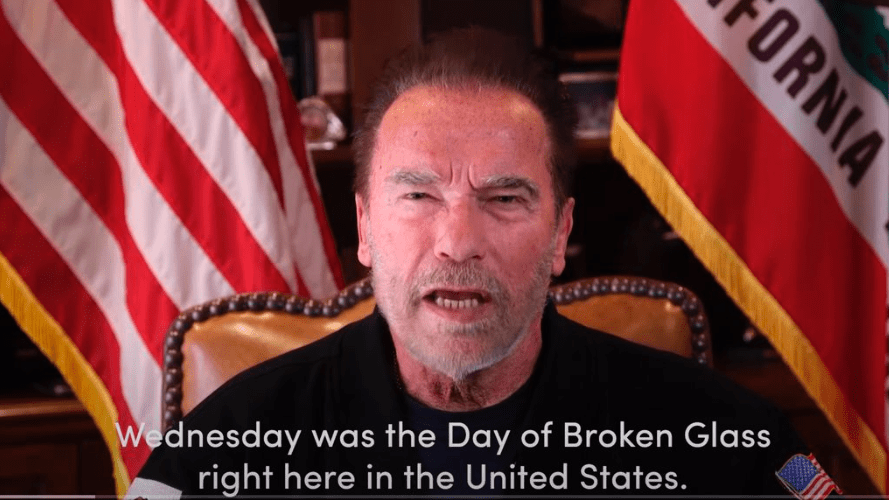

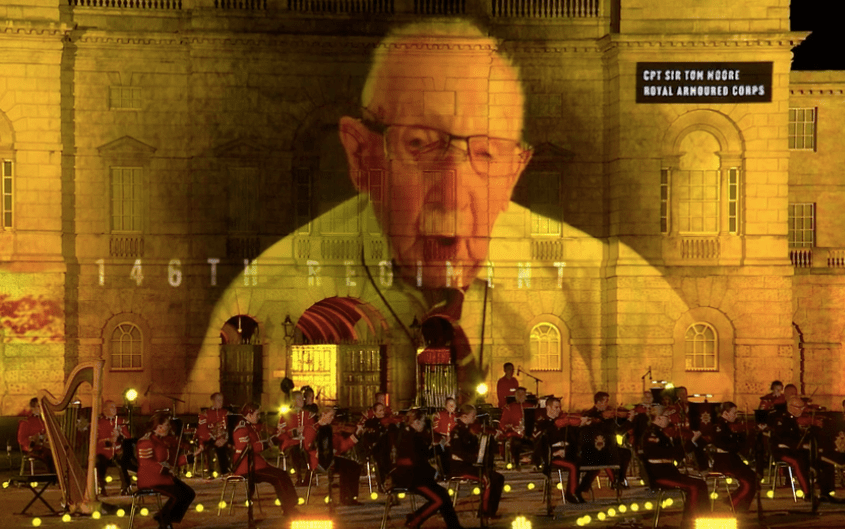

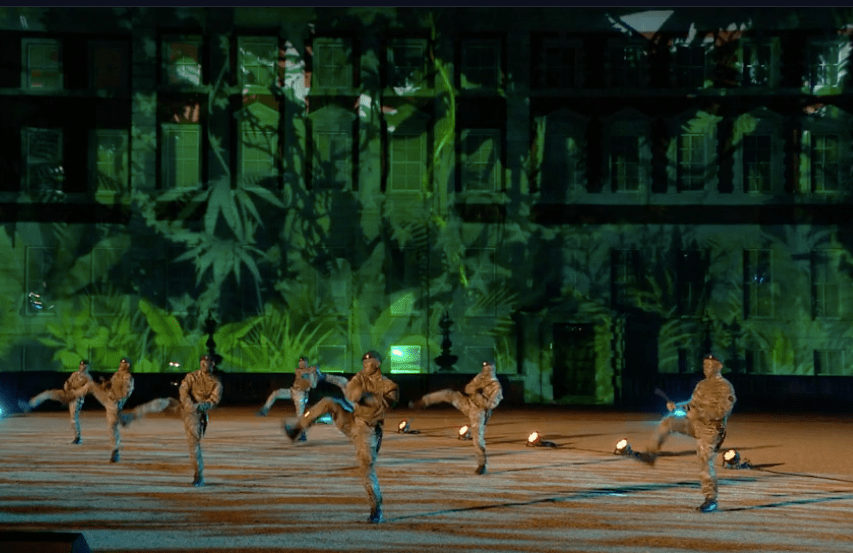

The last couple of years have seen the 75th anniversaries of many Second World War events: the D-Day landings, VE Day, VJ Day, the liberation of Auschwitz… Each was naturally ‘celebrated’ in technicolour with dignitaries from around the world, for these were some of our nation’s finest hours. Tucked in the shadows of those victories, was the 75th anniversary of the UK and USA bombing of Dresden. As far as I am aware, no British politician attended. Neither Boris Johnson nor Jeremy Corbyn even commented on it. It is still a thorn in the side of Britain’s conscience.

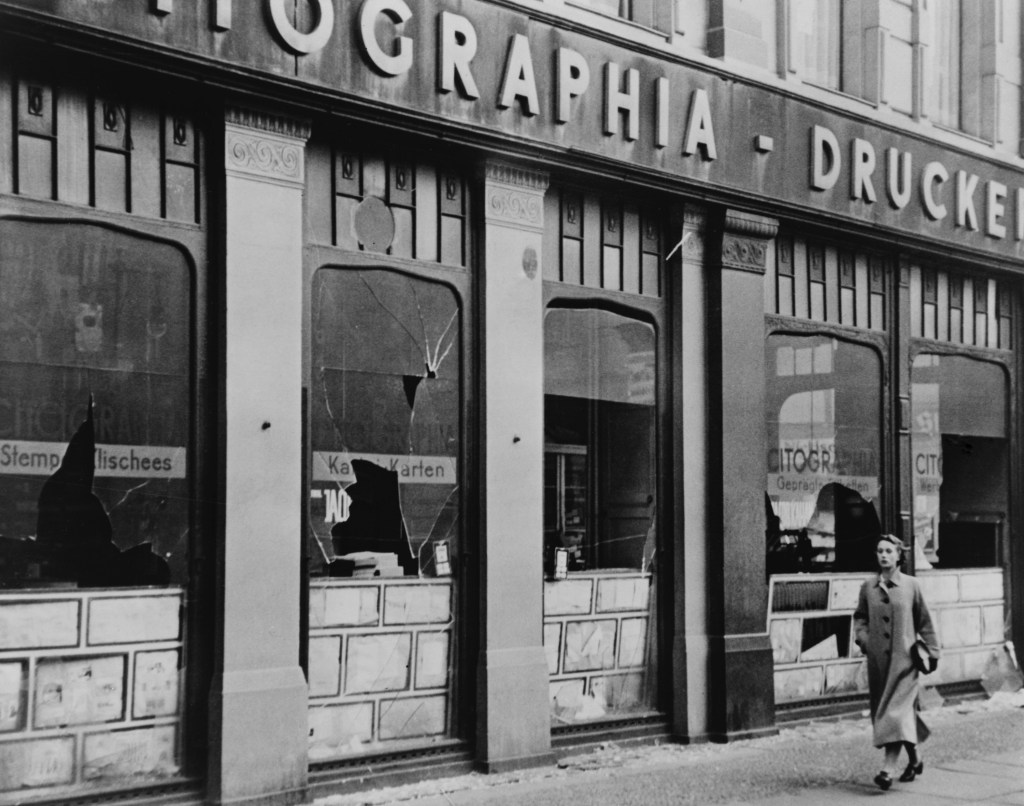

I am fully aware of the contention surrounding the bombing of Dresden. Was the city a legitimate target? Did the Germans deserve it? Was it a war crime? Were Bomber Harris and his Command heroes or part of a campaign that went too far… way too far? In the articles at the bottom of this post you can read up on some of these attitudes, as well as get a picture of the horrors witnessed by a British serviceman held prisoner there.

Seventy-six years on, I feel we are totally missing the point if we get tangled up in binary discussions of whether it was right or wrong. Within the context of Hitler and a World War, you can see how it could be considered ‘right’. On that basis, by reading some of my German grandfather’s letters, you can also see how it could have been considered ‘right’ to invade Russia. And by listening to the stories of prisoners, you can also come to understand how they too consider their crimes to have been the ‘right’ thing to have done. Wrongdoing – on an individual or national level – is usually based on thoughts that justify it as being the ‘right’ thing to do. Often this is a reaction designed to redress the wrongdoing of another… and so it goes on. The validity of the reasoning, however, doesn’t automatically make it the right thing to do morally.

We are living through extraordinary times of potential change for good. I say ‘potential’ because if we in Britain do not broaden our perspectives on our past in tune with history’s ever-shifting shape, we run the risk of becoming fossilised within it. Nothing can change if we cling to the old. The current statue debate, as provocatively and passionately pursued by Robert Jenrick, our secretary of state for housing, communities and institutions, is an example of the deeply flawed thinking at the core of some of our attitudes to the past. For him, statues represent history itself. Yet they don’t. They represent the values of the time. Both history and values evolve, and debating and adapting to this evolution are important parts of any country’s healthy relationship to its past. What’s more, focusing on statues is a classic example of merely treating the symptom rather than the cause of a problem.

While I don’t believe the removal (or not) of statues is either the real issue or the solution, the government’s evident terror of a ‘revisionist purge’ by ‘town hall militants,’ ‘woke worthies’ and ‘baying mobs’ is revealing. (And insulting to the justifiable requests for a reconsideration of the appropriateness of certain statues in today’s cities). It is the terror, not just of the dismantlement of our statues and heritage, but of our almost purely benign self-image. So great is that fear, that Mr Jenrick is giving himself the personal power to intervene in democratic decisions made by local communities, councils and institutions about the fate of their statues if their decisions don’t adhere to the government’s position. Is that democracy?

Our national self-image and reputation have already been considerably wobbled, if not toppled, in recent years. So I say, bring it on! Why don’t we just go for it? Why don’t we literally ‘come out’ officially and admit: We have… at times… been utter shits. Does that automatically diminish all that we hold dear and celebrate about ourselves? No, not at all. We can be all those good things AS WELL AS being, at times… shits. We can have done and achieved amazing things AS WELL AS having made mistakes, or been on the wrong side of good, or been actively, deliberately bad. We can honour our pilots and soldiers AS WELL AS deeply question the morality of some of our decisions. No country will think less of us… indeed I am sure they will embrace and welcome our vulnerability after so much bullish bluster.

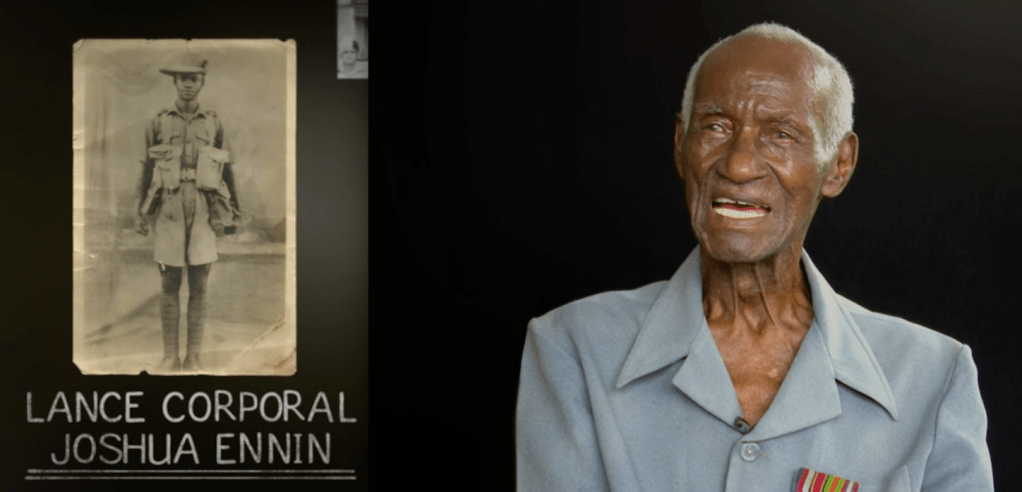

Until we can shift our position even just a little, Dresden will remain a contentious and unresolved issue. A dark smudge on the national conscience. Whether it was right or wrong, a war crime, an atrocity or a strategic attack, the fact remains that an estimated 25,000 people – primarily women, children, elderly, refugees and POWs – were killed in indescribably ghastly ways, by any standards of warfare. We deliberately designed it to be just so. Could this government, the successors of the instigators of such calculated destruction and loss of life, not also extend a small gesture of thought to the descendants of our victims?

In Mr Jenrick’s argument, “To tear [statues] down is, as the prime minister has said, ‘to lie about our history’.” If we really rely on our statues to tell the truth about our history, then we need to get carving and casting fast. For so far, only truths considered flattering or benign are being told. Nothing of the dark shadows cast by those men on pedestals is included in our statue-version of history. Doesn’t that then make it a lie…?

Past harm left unresolved is a burden that disrupts the present of each generation as it seeks resolution. It adversely shapes attitudes and policies. Let’s be the generation that works through the full truth of our past, creates peace with it and thereby liberates future generations from it.

In my forthcoming TEDx talk on 21st March 2021, I will be explaining How facing the past freed me. You can read more about it here and buy tickets to the event here

Related articles:

The Spectator: Did Britain commit a war crime in Dresden? A conversation Sinclair McKay and A.N. Wilson on the 75th anniversary of the bombing raid

Good Morning Britain 75th anniversary: Dresden bombing survivor Victor Gregg 100 on

Herald Scotland: Dresden 75th anniversary: why Britain must come to terms with its own dark wartime past

BBC: Dresden: The World War Two bombing 75 years on

The Telegraph: We will save Britain’s statues from the woke militants who want to censor our past (Robert Jenrick)

The Guardian: It’s not ‘censorship’ to question the statues in our public spaces

Please sign up to my NEWSLETTER to be kept up to date on my forthcoming BOOK on the subject here. To receive my monthly blog by email, press FOLLOW at the top of this page. Or contact me for any enquiries about my TALKS.