I am already anticipating a deeply divided and critical response to the recent announcement that Charlie Gladstone and five members of his family, all descendants of the Victorian-era prime minister William Gladstone, are travelling to Guyana to apologise for the significant role one of their ancestors played in the slave trade. But I’d like to ask those who are cynical of such a trip to consider what the alternatives might be.

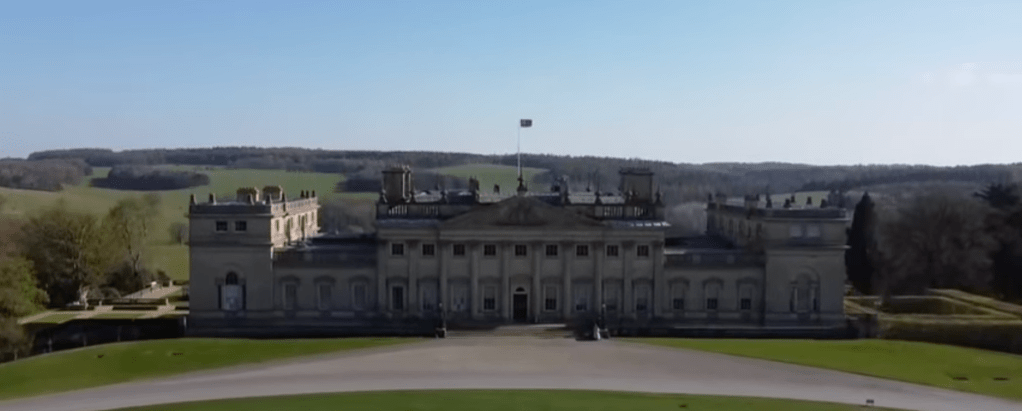

John Gladstone, William’s father, was one of the largest slave owners in the British West Indies. You can read all about him in the links at the end, but basically he made a fortune as a Demerara sugar planter enslaving hundreds of Africans to work in his plantations until slavery was abolished in 1833. He then became the fifth-largest beneficiary of the £20m fund (about £16 billion today) set aside by the British government in 1837 to compensate planters for loss of income. The final instalments of this compensation were paid out in 2015.

Charlie Gladstone is roughly the same age as me and, though the ‘crimes against humanity’ perpetrated by his family member were nearly 200 years ago whereas those my German grandfather was involved in were a mere eighty, the burden of shame may well weigh as heavily. As I describe in detail in my book, In My Grandfather’s Shadow, the unresolved deeds of our forefathers remain in a family blood line, in our roots. Whether you are ignorant of or choose to engage with them, there will be an impact that needs resolution of some sort.

Apology is one of many steps that can be taken to try to repair wrongdoing, and personally I think it is good that people such as those in the group Heirs of Slavery, including David Lascelles 8th Earl of Harewood, are finally beginning to address not only the sources of their family’s wealth, but also our collective colonial history and the traumatic consequences that can still be witnessed all too clearly in racism, inequalities in health, wealth, education and opportunity. In their cases it is about apology and accountability, with some of them making financial contributions towards charitable institutions and – in the Gladstone’s case – further research into the impact of the slave trade.

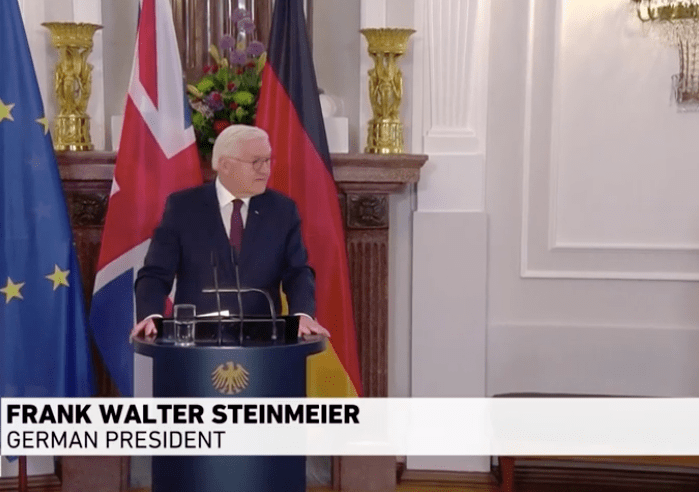

Others are at it too. Back in July, the Dutch King, Willem-Alexander, apologised on behalf of his country for the Netherland’s historical involvement in slavery and asked for forgiveness. It’s of course a flawed gesture in its incompleteness, but isn’t a heartfelt apology, whether possible or not so long after the event, at least a gesture of recognition of wrongdoing that can lead to a willingness to redress the former total loss of humanity? So many victim groups would attest to the immense value of a genuine ‘I’m sorry’.

Our prime minister doesn’t think so. Back in April, Rishi Sunak refused to apologise for UK’s role in slavery saying that ‘trying to unpick our history is not the right way forward’ and that the focus, ‘while of course understanding our history in all its parts and not running away from it, is making sure that we have a society that is inclusive and tolerant of people from all backgrounds.’

Fair point about looking forwards. But how can you truly ‘understand’ such a horrific history, underpinned by past government policy, without being moved to demonstrate some direct expression of remorse to those it continues to affect? Or is that precisely what we are scared of? That an apology equates to an admission of culpability and therefore an obligation to compensate?

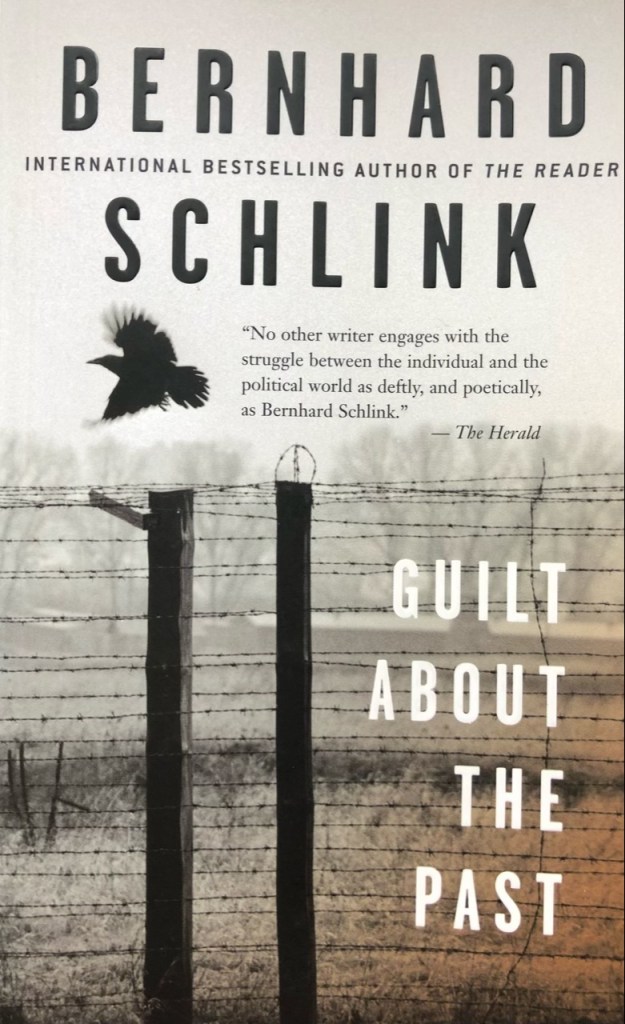

In his series of essays based on lectures delivered at Oxford University and bound into the 2009 book Guilt about the Past, Bernard Schlink, German author of the 1997 bestseller The Reader and various other literature, tackles not only German guilt about the past, but other long shadows of collective and global past guilt. (I am well aware we can’t actually be guilty of something we didn’t do, but we can still feel guilt.)

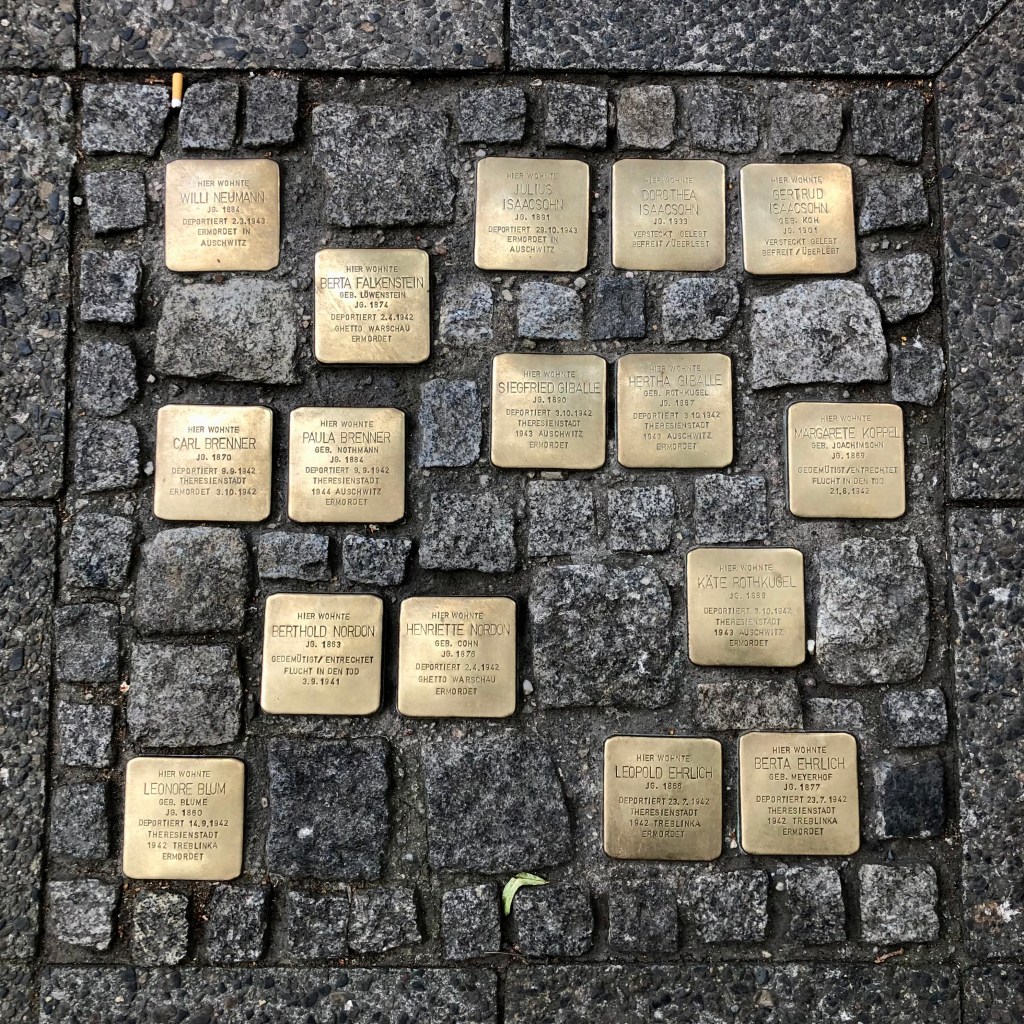

In the essay entitled ‘The Presence of the Past’, he addresses the issue of remembering or forgetting a traumatic past. “A collective past, like that of an individual, is traumatic when it is not allowed to be remembered and is just as much so if it has to be remembered… Detraumatisation is the process of becoming able to both remember and forget; it is leaving the past in the past, in a way that embraces remembrance as well as forgetting. This applies in the same way to the victims and their descendants as to the perpetrators and their descendants.” (p.36)

We need to find that balance.

One of Schlink’s claims that struck me most while exploring my own sense of guilt for my German family’s past was in the chapter on ‘Forgiveness and Reconciliation.’ He says that if someone seeks forgiveness for their own guilt it has weight, but “to ask for forgiveness for someone else’s guilt is cheap.” (p.73)

Cheap… So where does that leave those of us living today and the question of apology for things that happened decades or even centuries ago?

Schlink and I come to a similar conclusion. It’s about understanding. He says, any kind of reconciliation requires “a truth that can be understood.” And “true understanding is more than searching for and finding causes. It includes putting yourself in someone else’s place, putting yourself in someone else’s thoughts and someone else’s feelings and seeing the world through that person’s eyes.” Doing this, he says, establishes equality. “We make [the other person] equal to us and us to them; we build up society when we understand.” (p.82)

This form of ‘understanding’ goes way beyond the slightly glib understanding the current leader of our country suggests. It requires engaging in the truth of what happened and feeling it. Feeling how appalling it was and being moved to act to heal and make good the wrongs that still poison our national veins and those of the human beings living today whose forefathers were harmed.

Further reading, as always not all links reflect my own opinions:

William Gladstone: family of former British PM to apologise for links to slavery

William Gladstone’s family to apologise for historic links to slavery

‘I felt absolutely sick’: John Gladstone’s heir on his family’s role in slavery

Rishi Sunak rejects calls for slavery reparations from UK

When will Britain face up to its crimes against humanity?

Dutch king apologises for country’s historical involvement in slavery

Campaigners urge king to do more to acknowledge UK’s slavery role

The British aristocratic families reckoning with their slave owning past

The German translation of In My Grandfather’s Shadow will be published in Germany in September. Please contact me for details of forthcoming events relating to in Germany.

Title painting: ‘Salt of the African earth‘ by Angela Findlay, 1994