(If you are joining Joan’s story now, you might want to read Following Joan… Parts One and Two first.)

‘Do you think she jumped… or did she fall?’

It’s 2020 and I am sitting opposite my uncle, a grandfather clock tick-tocking the present into the past.

That question has always lingered around the name of my Great Great Aunt Joan. She was said to have been troubled, never having recovered from the death of her beloved older brother, Gerald, killed at Gallipoli in the First World War. Ill health had dogged her. And as another war loomed on the horizon, perhaps she could not bear to witness more loss.

I sometimes wish I could type ‘Joan Legge’ into the search box of my life’s hard drive to locate the exact moment her story began to intrigue me. Perhaps it was a conversation with my grandmother, Joan’s niece. Both she and her younger sister had believed, independently, that Joan would not return from her trip to the Himalayas in 1939. Their mother was said to have ‘the gift’ – an unfathomable intuition, a form of knowing that slips past reason.

That fascinated me, for even as a child I sensed there were hidden channels of communication and knowledge beneath the surface of ordinary life. Perhaps their foreboding of no return planted the idea that Joan’s death had been deliberate.

Or maybe it came from the anecdotes I gleaned over time from my father and uncle about this eccentric spinster who, after Gerald’s death, cast off the frills and trappings of aristocracy and privilege to forge a life of farming, service and adventure. A life that ended in solitude, in a remote valley half a world away.

Some lives close with a sense of completeness, even peace. Death may be welcomed after a struggle with illness or the slow wear of age. Others remain unfinished, wrapped in mystery, unresolved, tugging at the conscience of descendants like a child clutching at its mother’s apron strings.

Joan’s sudden death was of that latter kind. It sent shock waves through the generations, softening with distance into small ripples. Even now they lap at the shores of my own soul.

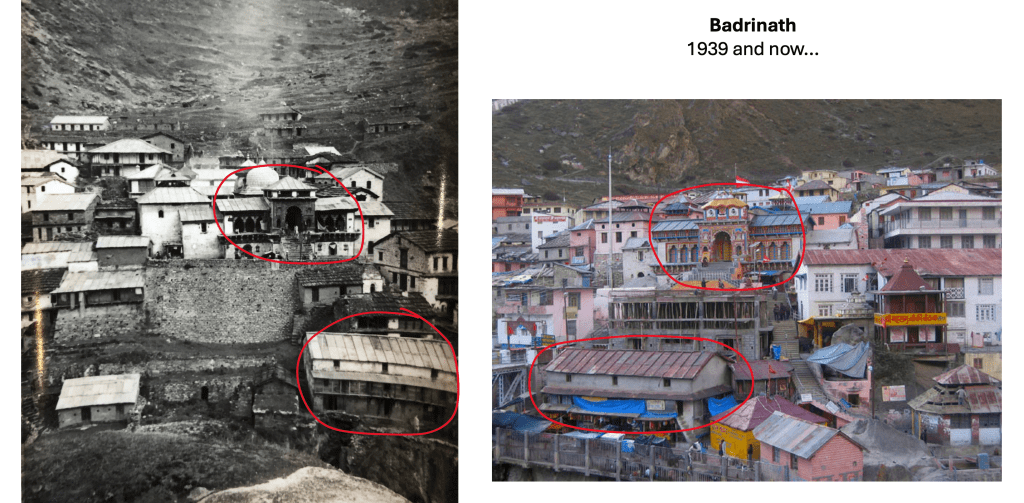

©Staffordshire History Centre

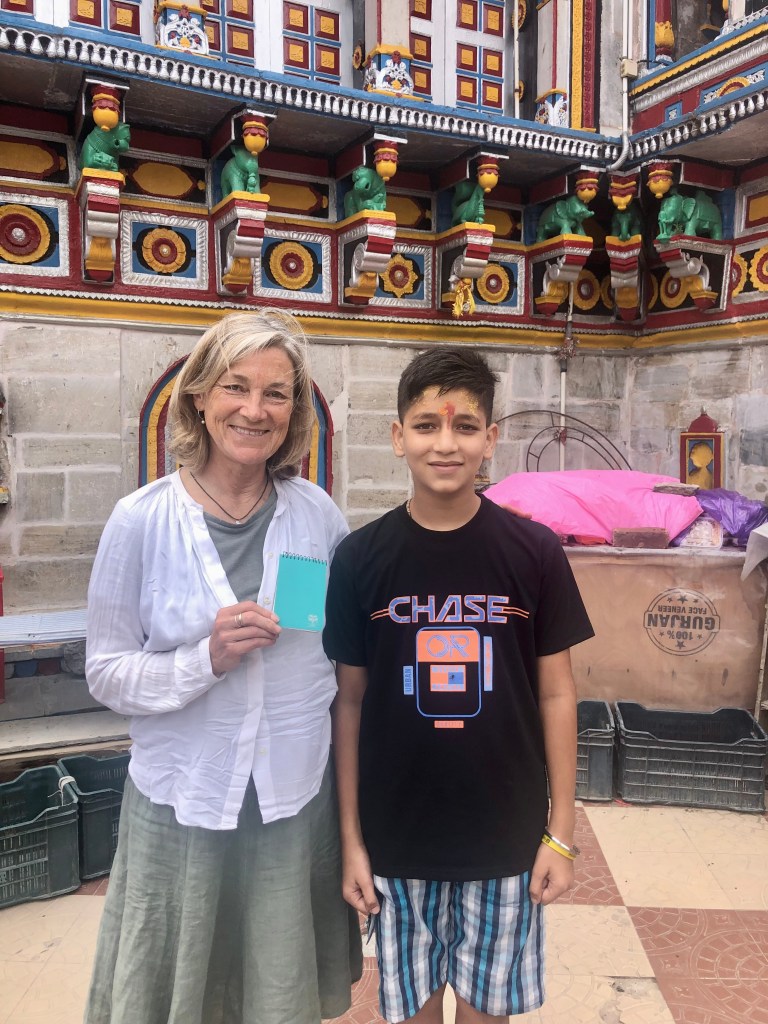

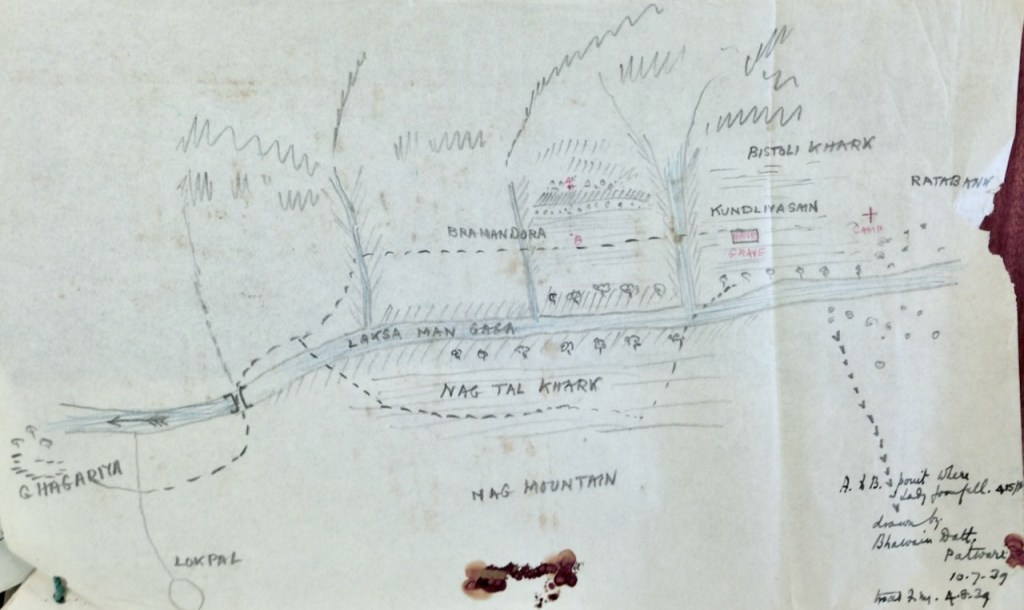

It was only last year, travelling to the Valley of Flowers with three of Joan’s descendants, that I fully grasped the scale of her courage. And the violence of her end. The monsoon rains offered us just a fleeting glimpse of the place she fell, its position traced on a map sketched in the days after her death. Yet it was enough to shatter the gentler image I had long created of her tumbling down a wooded slope. The truth was starker. Joan had fallen clean over the edge of a sheer granite cliff.

Her fall haunts me. Those unthinkable seconds of awareness, knowing you are hurtling toward your end. How different from a death that comes inch by inch, offering time to prepare, to resist, to rage, or to reconcile. In July 2024, when I left the Valley of Flowers and Joan’s remote grave, a sudden grief overwhelmed me, buckling my legs and landing me in a pile of donkey droppings. Yet Joan’s own words leave no room for doubt. Her diaries brimmed with excitement for the months ahead, with awe for the surrounding peaks, and with delight in her adventure. She did not choose death. She was very much alive.

So why does her story touch me so deeply? Why not my great grandmother, killed in a car crash? Why not my grandfather, the ‘muck and magic man’, pioneer of organic farming? Why Joan? And why me – the only one in the family drawn, again and again, to the lives behind us rather than those unfolding ahead? Is it because I have no children to anchor my gaze forward? Or is it that I have no children precisely because the voices behind me insisted on my attention?

Perhaps neither, or both. What I do know is that the dead have enriched my life. And in honouring them, in breaking the silence of the unspoken, in unravelling the mysteries and untangling the knots they left behind, I believe their presence has enriched the lives of others’ too.

Through my recent studies in Family Constellations, I have increasingly come to experience life as a river, flowing on with or without us. We step into its current for longer or shorter spans, mingling in the same waters where our predecessors once moved. What matters is not the length of time, but the resonance we leave behind. Not quantity, but quality.

Birth is the one beginning we all share. But our endings are as varied as our lives. Accident, chance, destiny, choice… no one can know death’s moment or manner, only its inevitability.

So was Joan’s death a tragedy as her obituaries mourned? Or was it a brilliant ending to a life lived fully right into its final breath?

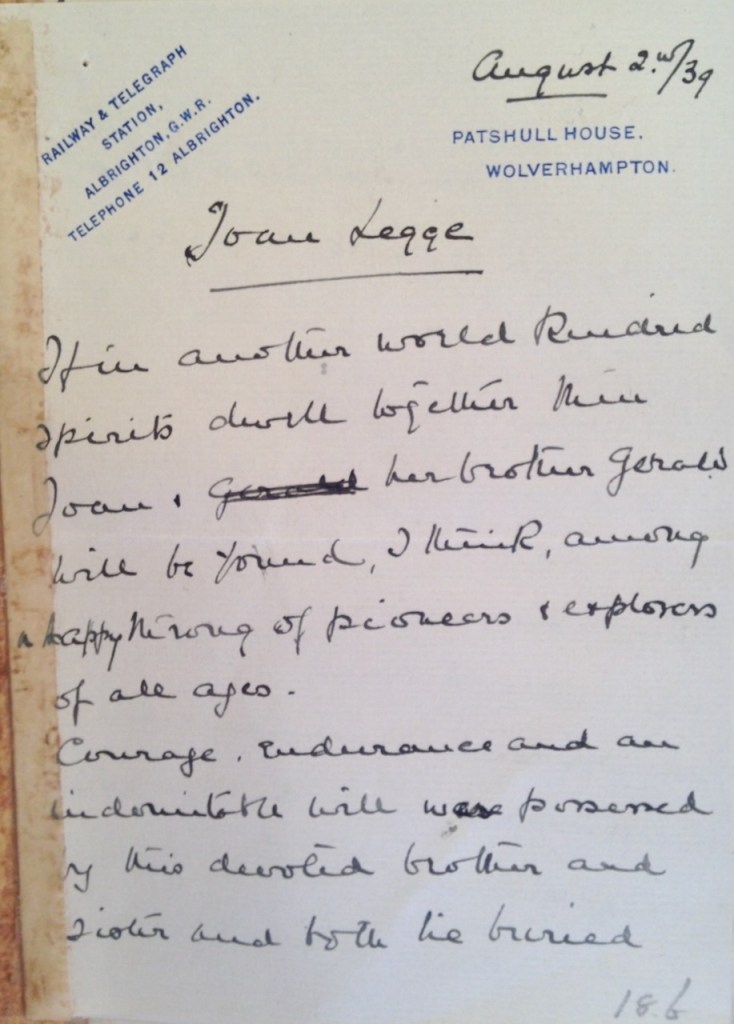

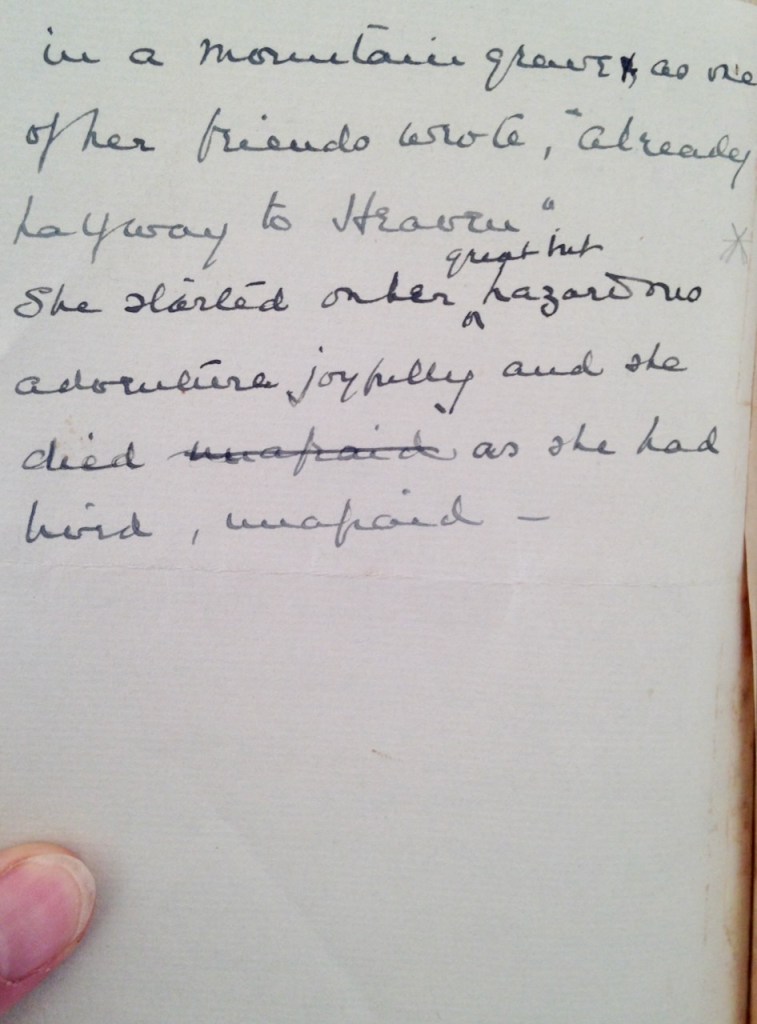

Draft for Joan’s eulogy by her sister: ‘If in another world kindred spirits dwell together there Joan & her brother Gerald will be found, I think, among a happy throng of pioneers and explorers of all ages. Courage, endurance and an indomitable will were possessed by this devoted brother and sister and both lie buried in a mountain grave & as one of her friends wrote, ‘”already halfway to Heaven”. She started on her greatest hazardous adventure joyfully and she died as she had lived, unafraid – ‘

I dedicate this blog to my dear friend in Australia, Tas. Over the past six years, corticobasal syndrome (CBS) has been claiming his body, his movement, his speech. And yet his spirit, his humour, his integrity and his enduring delight in friends, family and life itself still blaze. To know him is both an inspiration and a gift I deeply treasure.

Further details of my exhibition / event on Joan will follow in my next Blog.