April saw the death of the widely loved Pope Francis, the Jewish festival of Passover, and the gradual build-up to the 80th Anniversary of VE Day (Victory in Europe) in May. An unusual trio of events, yet radio coverage of all three wove threads of reflection into the tapestry of this blog.

Compassion was central to Pope Francis’s papacy – particularly towards those who are rejected or marginalised. He often spoke about the importance of honouring and never abandoning our grandparents. “If you want to be a sign of hope, go and talk to your grandfather,” he was quoted as saying. They remind us that we share the same heritage, link us to “the beauty of being part of a much larger history… a loving plan [that] is greater than we are.” He also had the humility to say “I am a sinner,” which makes me wonder where that leaves the rest of us!

In a recent Radio 4 Thought for the Day (at 1:47:45), Chief Rabbi Sir Ephraim Mirvis described Passover as the ‘Festival of Questions;’ a time to ask, to probe, to test assumptions, refine our understanding and uncover the truth.

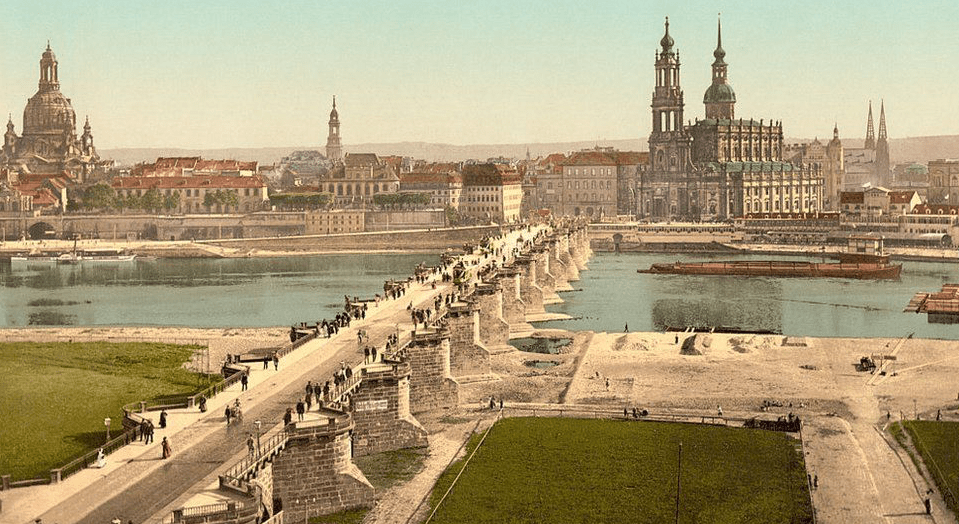

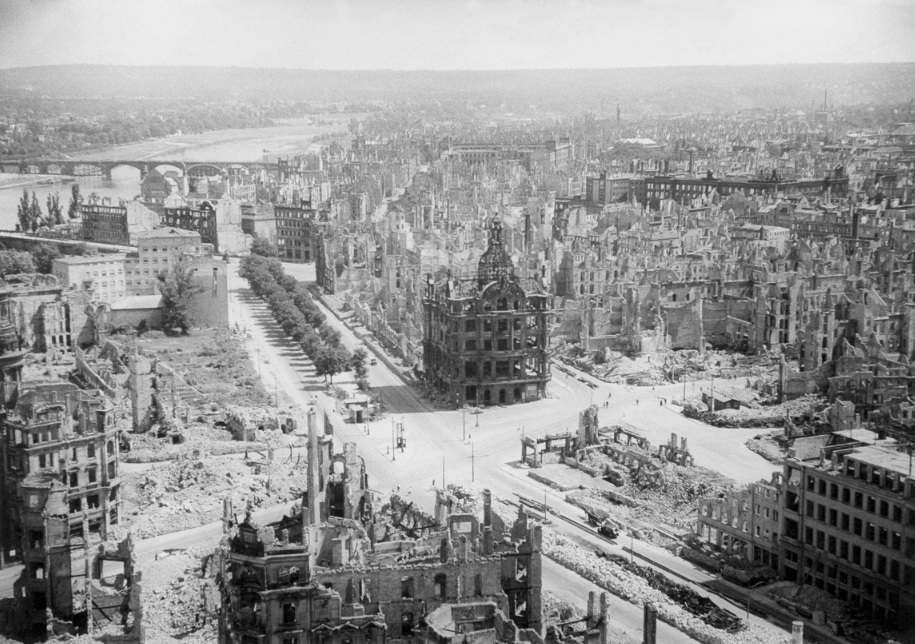

If we try to apply the guidance of both spiritual leaders to the forthcoming celebrations of VE Day on 8th May, we may find ourselves asking how the grandchildren of the ‘losers’ of WWII – many of whom had been perpetrators or complicit in Nazi atrocities – might ‘honour’ their grandfathers. How do you love – should you even try to love – someone who has acted immorally, abhorrently, even if those acts were sanctioned or ordered by a higher authority and deemed the right thing to do for Volk and country?

I’m all too aware how unfashionable, controversial and even provocative it is to suggest we spare a thought for the perpetrators. But in keeping with the spirit of my triangle, I am going to ask you to do just that. Many people, from all sides of the conflict, are quick to judge, blame and damn the Wehrmacht soldiers and SS as an indiscriminate mob of ‘monsters’, all morally inferior and wholly undeserving of being remembered. It’s completely understandable. But where does that leave their children and grandchildren? What happens when we continue to draw a line between the ‘good us’ and ‘bad them’, a distinction that may have served its time but no longer helps us move forward? Isn’t one of the most crucial lessons of this horrific chapter in history to recognise that most perpetrators were not monsters, but ordinary people… like you and me… who, through a slow drift of compromise, small decisions and ill judgements became capable of unimaginably heinous crimes?

Eighty years on, with more than 88% of the German population having been born after the war’s end and a further 11% still children at the time, it’s difficult to place ‘guilt’ for the Holocaust on the Germans of today. After all, people cannot be guilty of things they themselves didn’t do. Yet, like many descendants of Holocaust victims and survivors, some non-Jewish Germans born in the decades after the war still wrestle, often unknowingly, with the unresolved trauma and guilt passed down from their parents or grandparents. They carry what Eva Hoffman aptly described as “the scars without the wound” – invisible wounds that silently shape their internal world and influence their actions in the external world.

Without detracting anything from the horrors and suffering of the victims, can we imagine for a moment how it might be for post-war generations of Germans to live with legacies of silence, cover-ups, not-knowing, judgement, exclusion, blame or shame in relation to their roots? Mistrusting family stories. Wondering who knew and who did what. What impact does this have on individuals, families, societies, nations and ultimately, the wider world? How can one best deal with such a profound inheritance?

Primo Levi – who, as a Holocaust survivor had every right to think the opposite – declared that collective guilt does not exist. To think that it does is a relapse into Nazi ideology. Both he and Hannah Arendt made a powerful claim: “We are all to blame” for what happened. Collective responsibility is what matters. And that involves understanding how atrocities occur both in society and within the individual. How we become complicit.

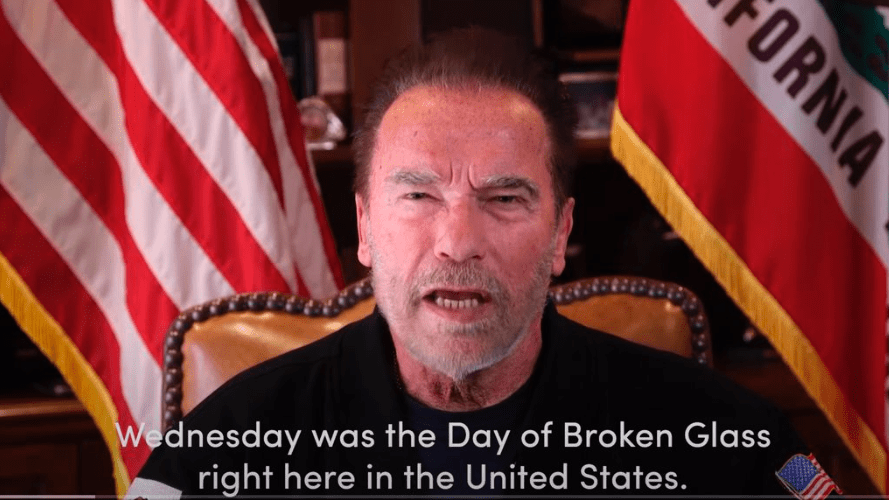

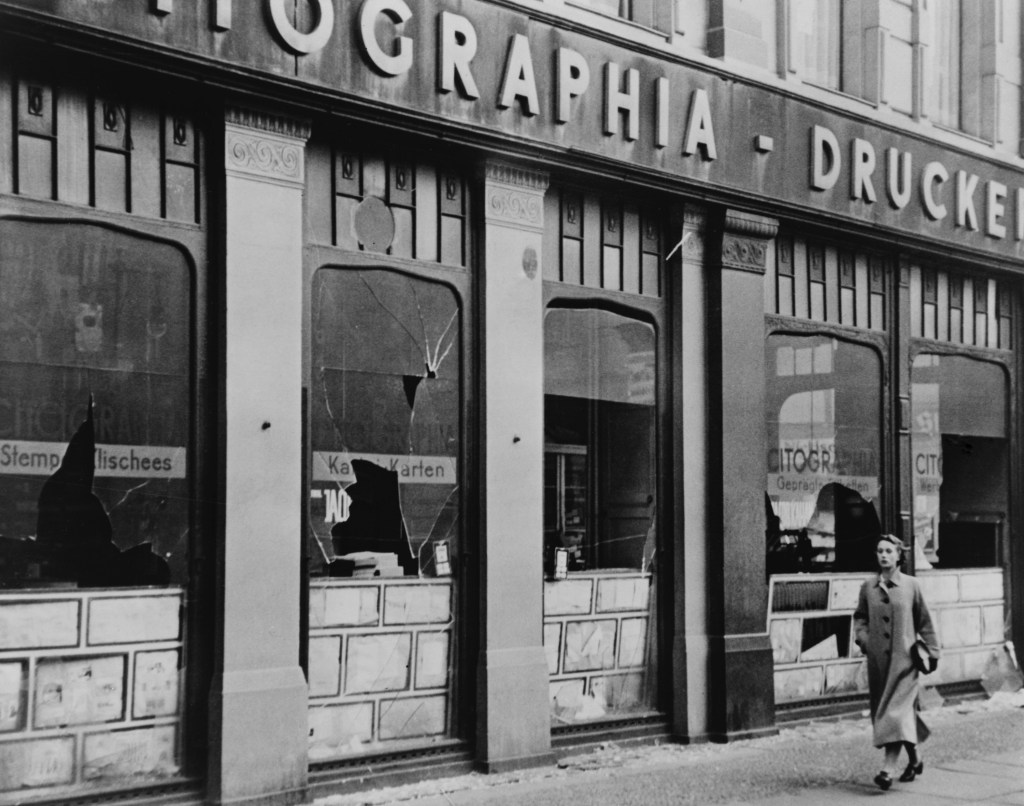

The roots of Nazism found fertile soil in the humiliation wrought by the terms of the Treaty of Versailles and the deeply resented ‘guilt clause’ that placed full blame for WW1 solely on Germany’s shoulders. Applying a similar dynamic to today, could there be a connection between this historical pattern and the rise of the AfD (Alternative für Deutschland), Germany’s nationalist far-right party — a movement fuelled in part by a desire to reassert national pride and, as encouraged by figures like Elon Musk, to move beyond what they perceive as an excessive “focus on Nazi guilt”?

The 2019 survey previously cited revealed that few Germans actually feel guilt and 70% (including 87% of AfD voters) believe their country has now sufficiently atoned for the actions of the Nazi regime. Another source revealed that 75% of young Germans (erroneously) believe they come from families of resistors, while 25% can’t name a single concentration camp or ghetto. As the number of living contemporary witnesses dwindles, disinformation, denial and delusions are spreading. With them, the sense of responsibility risks disappearing too – a deeply worrying and dangerous trend. Knowing firsthand the insidiously destructive effects of being shamed for a familial association with the Nazi era, I can understand how, eighty years on, rejecting any semblance of inherited guilt might feel like a healthy response. After all, who among us wants to feel terminally tainted by the wrongdoings of their forebears? Who wants to have to cut off their roots?

I feel fortunate that, while living in England with my German heritage was at times challenging, my parents and their families modelled true reconciliation throughout my life. My British father and German mother married just 17 years after the Second World War ended. Both their families had suffered and lost loved ones and/or homes under the others’ military objectives. Yet both found the courage to drop into their hearts and overcome division and enmity. And that, to me, is where the solution lies: in our hearts.

Patriotism is hollow if it is based only on pride and honour. Shame and conscience lead to a deeper bond. Seeing the world in binaries – in terms of ‘us’ and ‘them, good and bad, right and wrong – shuts down love. Reconciliation becomes impossible. As Britain celebrates its triumph over the evil forces, let us also remember we were not all good and they all bad. Among other short-comings, we too were guilty of antisemitism and of failing to help the Jews more.

In another recent Thought for the Day, Rhidian Brook warned, “If you can’t see the other side’s humanity, you’ve lost.”

My 80th Anniversary VE Day wish, therefore, as both a British and German citizen, is for us to follow the example set by the late Pope and Chief Rabbi: to think, to probe, to get uncomfortable, and to find compassion for individuals among the rejected and ostracised.

Eighty years on, might this be the moment to create new rituals of peacekeeping and unity? Without dampening the spirit of national joy, how can we include – and stand hand-in-hand with – our contemporary German friends in celebrations of peace, rather than reinforce historical divides?

Can we develop broader, more expansive narratives that encourage younger generations of Germans to face the difficult and painful truths of their families’ histories and to assume responsibility, not for what was done, but for what is still to be done? Can we remain vigilant against resting on any imagined moral high ground, against believing we would have undoubtedly been resistors and heroes under the Nazi regime? And can we instead recognise how thin the ice of democracy is becoming once again, and how difficult it is, even now, to change the course of history?

Events coming up:

Friday 2nd May, 12-1pm

The Second World War 80 years on: Is Remembrance Working?

Angela Findlay and Henry Montgomery In Conversation

National Army Museum, Royal Hospital Road, Chelsea, London SW3 4HT and ONLINE

80 years on from the German surrender to the Allies, Henry Montgomery, grandson of Field Marshal Bernard ‘Monty’ Montgomery and Angela Findlay, granddaughter of General Karl von Graffen of the German Wehrmacht will reflect on their grandfathers’ roles and actions in WW2 and discuss the differences in the histories, legacies and remembrance cultures of the victors and the losers and how Remembrance can remain meaningful and effective for younger generations.

Info and tickets (free) here.

Thursday 8th May, 18.00 – 19.30

Im Schatten Meines Großvaters / In My Grandfather’s Shadow

Vortrag und Gespräch / Lecture and Conversation

Marktkirche, Hanns-Lilje-Platz, 30159 Hannover, Germany

Thursday 15th May, 17.00 – 19.00 (UK time) 43. Gesprächslabor, PAKH: The Study Group on Intergenerational Consequences of the Holocaust (ONLINE)? Drawing on my own experiences outlined in my book, In My Grandfather’s Shadow, we will be discussing how such a destructive legacy can be transformed into constructive, reconciliatory approaches and positive actions. More info here: https://www.pakh.de/event/gespraechslabor-40/

Buy or read reviews on my book, In My Grandfather’s Shadow, here