“It’s brutal.”

That’s how a friend recently described being an artist. He had been a student at Goldsmiths in the late eighties and early nineties, during the rise of the Young British Artists (YBAs) like Damien Hirst, Tracy Emin and Sarah Lucas, names that would go on to dominate the art world, thanks in part to the patronage of Charles Saatchi.

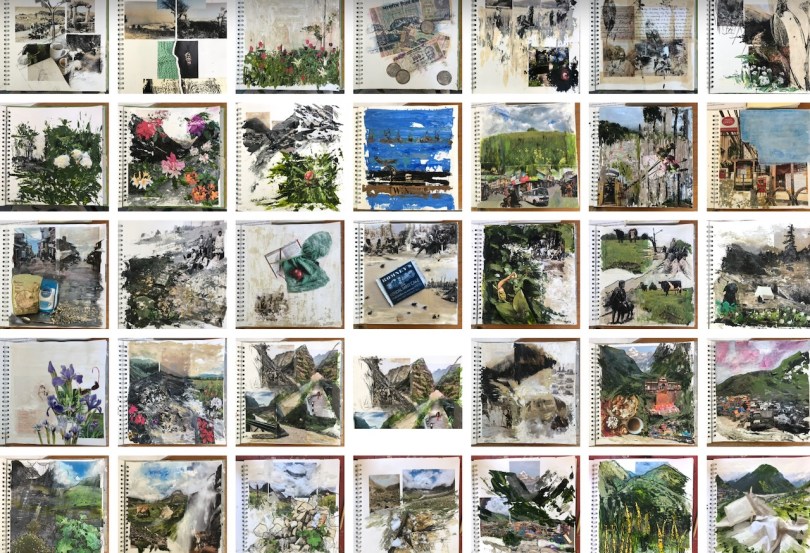

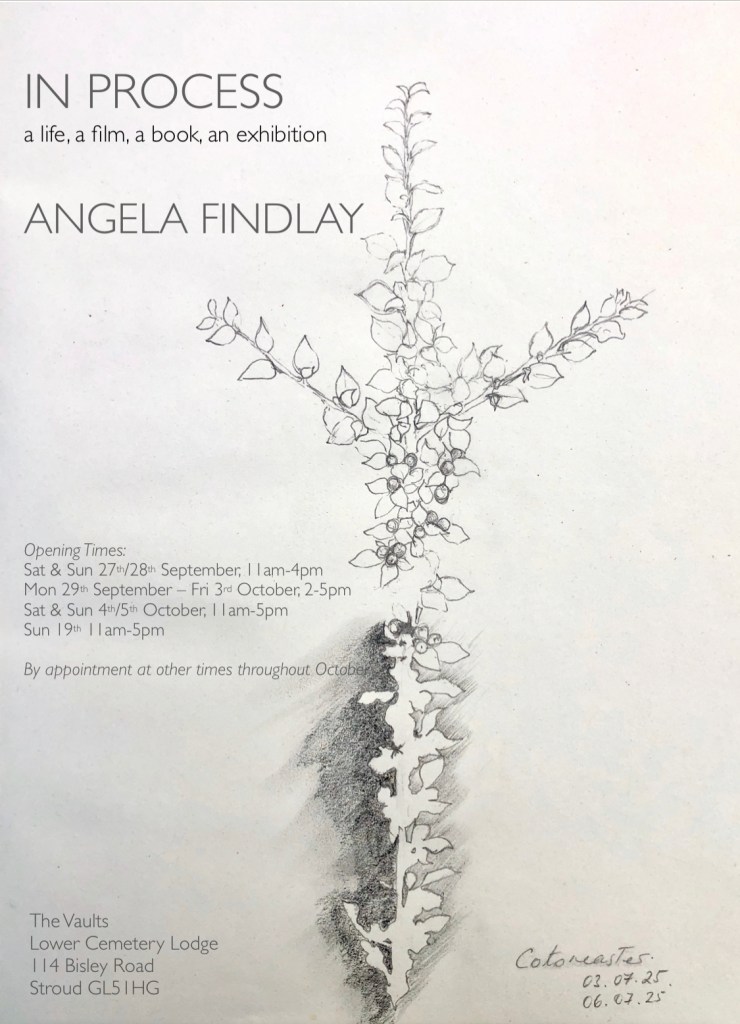

We ran into each other at the local paint shop—a regular stop for him in his current life as a decorator. Across a spread of tester pots and fillers, the conversation effortlessly turned to the day-to-day grind of being an artist. Over the summer I have been preparing for my forthcoming exhibition, In Process… (which opens today, 27th September!) and was feeling the impact of long, solitary studio days, wrestling with questions only I was posing and whose answers seemed only to matter to me. It can be a struggle: adhering to a discipline of showing up as captain to a ship with no passengers, steering a course to a nebulous destination, deep-diving into the depths of the soul, mind or body – wherever the well of creativity bubbles up – to haul tiny gems to the surface. Exhaustion and self-doubt often creep in.

‘What’s the point?’ is the main saboteur. The work seems irrelevant, the purpose elusive. There’s no financial gain, just costs. In the isolation of the studio, there’s no one to argue with those thoughts. Indeed it is easy to agree with them: Why bother?

And in times of widespread destruction – whether global or even personal – that sense of futility can grow.

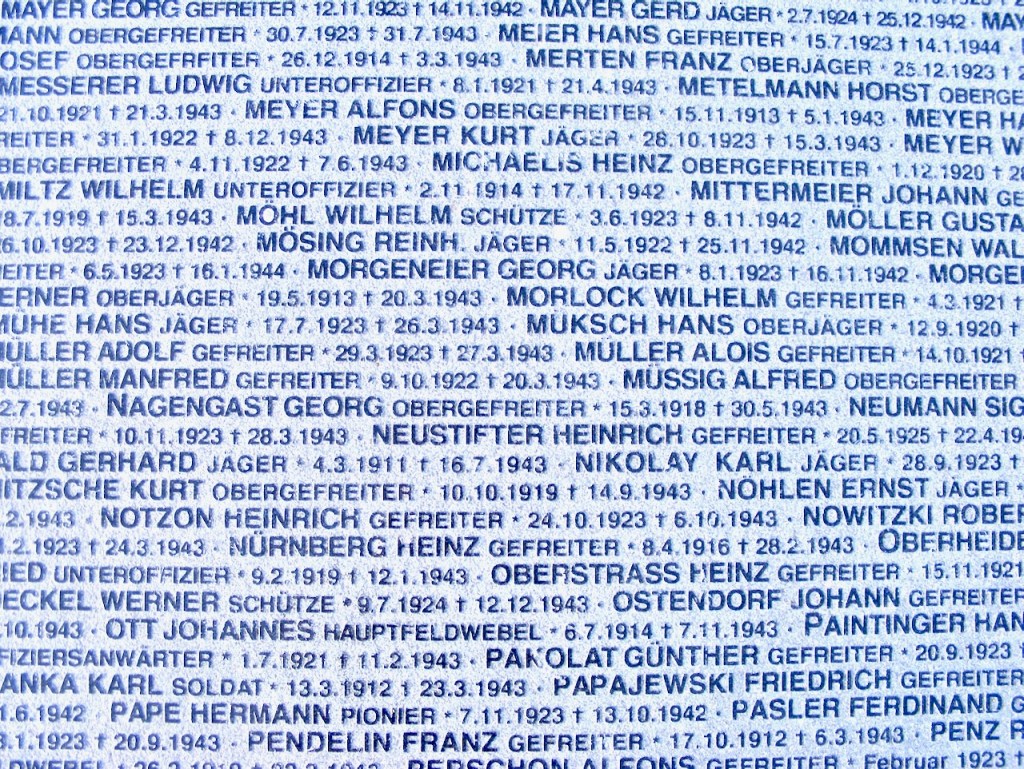

This summer, for example, parts of my home were stripped back to their foundations. My life was overtaken by builders, noise, dusty cups of coffee and chaos. Creativity felt all but impossible. In the grand scheme of things, this was a minor inconvenience. Soon, things would return to normal. But what about those whose lives have been shattered by larger forces… wars, displacement, destruction and poverty on a massive scale? How does creativity find its place amidst the rubble of Gaza, Ukraine, or other war-torn regions? Or even amongst the devastating images that make their way into our minds?

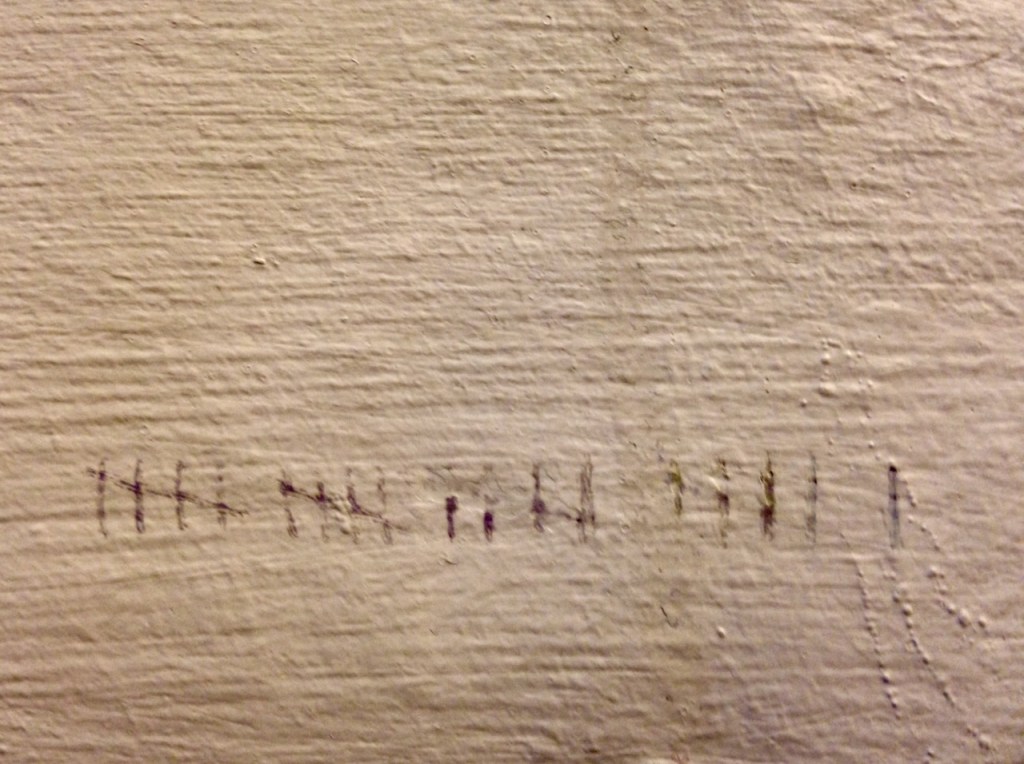

History has shown that creativity can thrive in the moments when everything appears to be falling apart. Creative expression becomes a form of resilience, opposition, even survival. It can be a small act of regaining control in an otherwise uncontrollable situation; a conduit for grief, an out-breath for trauma, a balm for moral wounds. Marks on walls or scraps of paper cry out: I am still here.

In today’s news-filled world where conflicts and politics pitch people against each other while social media distracts and distorts, I feel the call to act. To do or say something that will make a difference. I contemplate taking to the streets and marching in protest. Or superglueing myself to a pavement. I wonder if ‘speaking out’ involves publishing endless blogs and posts on social media denouncing what (I feel) is wrong? Ineffectuality wears one down.

But to me, the direction of the human race is a force majeure, too big for even the Trump to halt. We find ourselves swept in its rampageous current, both unwilling cogs in the destruction of things we once valued, and parts of an optimistic surge to re-build better. I feel feeble and impotent. When I can’t even open the lid on a jar of gherkins, how can I shift anything of significance? But maybe this disorientating maelstrom is precisely the context in which creativity becomes most vital. Maybe the internal orientation creativity demands provides a space for the mind to process, to breathe, to make light of the weight and sense of the senseless, and to find fragments of meaning in what frequently seems like an overwhelming mess.

Destruction can’t defeat creativity; it calls it forth, demanding that we seek beauty, purpose and points of connection. That process can feel ‘brutal’. What’s the point? is never far away. But I try to remember: The point is not always to create something monumental. Nor is it to offer neat answers. Sometimes, the point is simply to make something that wasn’t there before, to keep moving forward and to hold onto the belief that every act of creation – however small and seemingly insignificant – is a counter movement, an act of defiance, a stand against that which threatens to destroy us.

I have heaved my most recent exhibition out of a time of dark chaos. But as I – and it – clawed our way to the surface, it grew its own wings. Help came from unexpected places. Beauty emerged. And now it is there, in the Vaults, among the grapes on my vine, fruits to share.

There was a point!

You are so welcome to visit.

In Process… Opening Times:

- Saturday & Sunday 27th/28th September, 11am-4pm

- Monday 29th September – Friday 3rd October, 2-5pm

- Saturday & Sunday 4th/5th October, 11am-5pm

- Sunday 19th October 11am-5pm

- And by appointment at other times throughout October (excluding 10th–17th and 22nd–26th October)

If you would like more context to the work in the exhibition prior to coming, please read my previous three blogs: Following Joan… Parts One, Two & Three.