One of the things that struck me most on my recent trip to Australia was how far the country has come in the 37 years since my first visit. Above all, in acknowledging the darkest aspects of its colonial past: the dispossession, dispersal, and inhumane treatment of First Nations peoples.

It is far from a given that a country admits, let alone apologises and atones for past wrongdoings. One could also question if it is even possible or right for a subsequent generation to apologise for the errors of a previous one. But that is what I found in today’s Australia where few locations or tourist sites, art galleries or museums, brochures or signage do not have a written acknowledgement of a specific Aboriginal people as the rightful custodians of the land. In addition, there are frequently pledges committing to respect these Traditional Owners going forward.

This is a welcome overturning of the 1835 legal principle of terra nullius – land belonging to no-one – that was implemented throughout Australia as the basis for British settlement and the negation of Aboriginal people as being civilised enough to be capable of land ownership. Even personal email signatures are now used to underline an individual’s support and respect.

I acknowledge the Whadjuk People of the Noongar Nation as the custodians of the land I live and work on.

I respect their enduring culture, their contribution to this city’s life, and their Elders, past and present.

Back in 1986 when I lived in Sydney, I encountered small groups of activists who fought for Aboriginal rights. But attitudes outside the cities, despite the successful 1967 referendum, remained far from close to recognising Australia’s indigenous people as equal citizens in their own land. Even decades after the extreme discriminations of Nazi Germany’s anti-Semitic laws and actions had horrified the world, Aboriginal people were regarded as ‘wards of the state’. They were unable to own property or control their own money; they were not allowed to marry or travel without permission. If they lived in or around white communities they were segregated and prevented from using community swimming pools or sitting where they chose in a cinema.

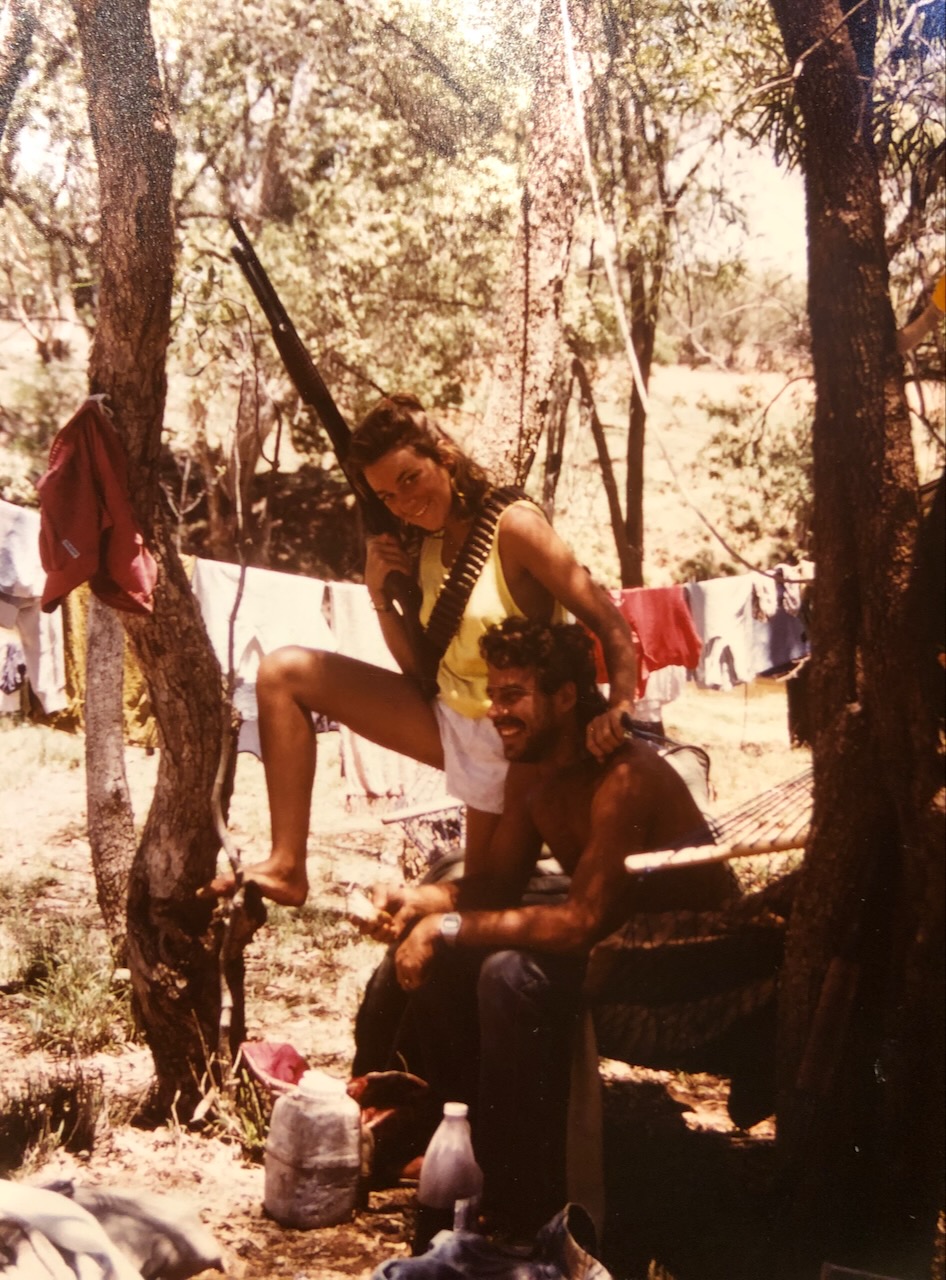

I have clear memories of my naive but adventurous, just-turned 22-year-old self bouncing across the north-eastern outback in chunky 4WDs driven by wild ockers. I remember a shoot-out at a nightclub… apparently some Aboriginals were shot at… and us fleeing the scene with extinguished headlights. The police showed up the next morning at our temporary camp on the banks of a (crocodile-infested?) river. They were not interested in the array of guns propped up against the trees, even though these could have been (but thankfully weren’t) the weapons turned against the Aboriginals. Nor did they question the men who would have used them. With apparent nods of approval to the young men’s armoury, the officers demanded to see my passport instead and carted off my terrified, less-ockery dope-head boyfriend for owning a pair of hash scales so tiny they couldn’t possibly have belonged to a dealer warranting incarceration.

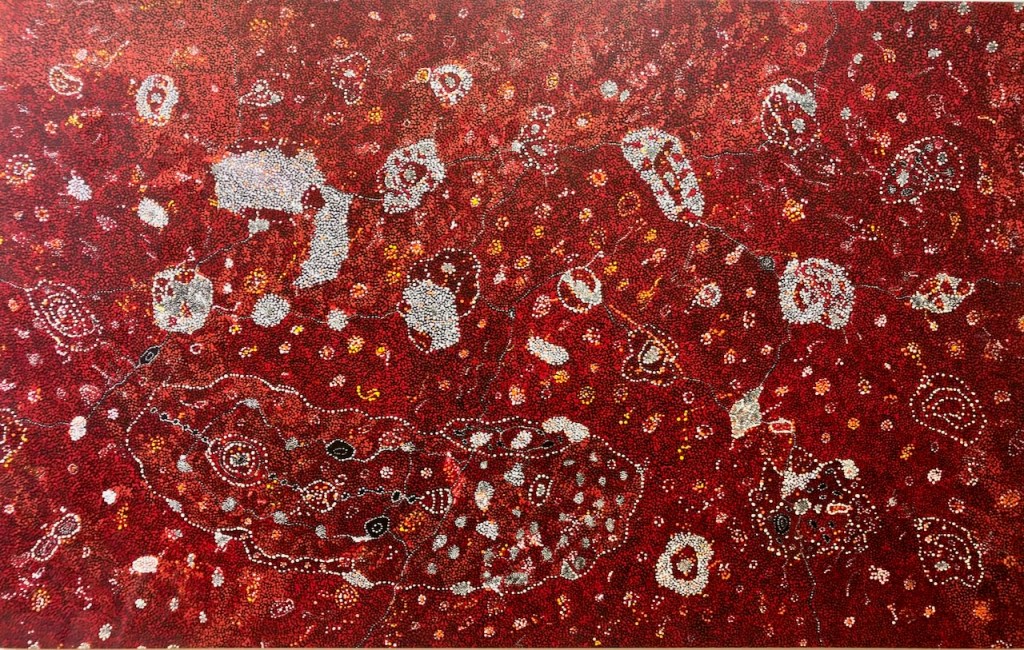

This was ‘normal’, I was told back then in response to my instinctive horror at the lack of concern for the welfare of Aboriginal people. Apart from the obvious abhorrence of such a ‘normality’, my natural tendency to root for the underdog was just one reason it all felt so wrong. Another was an inexplicable appreciation of Aboriginal culture with its ephemeral, ceremonial nature and absence of material evidence in the usual forms of temples and artefacts. I loved the simple power of their ancient handprints. The completeness of reality captured in the collections of dot paintings that began to emerge from the deserts in the seventies. I painted with earth pigments in the colours of their art. White, simply put, is the colour of spirit, black is the night, red is the land or blood, and yellow is the sun and the sacred.

I also attended what must have been one of the first Laura Dance Festivals, a 3-day gathering of dance troupes from across Cape York and the Torres Straits held on a sacred site about 4 hours’ drive north of Cairns.

My photo album recalls how the Chairman of the festival arrived 2 hours late and, clad in a grass skirt and white and ochre stripes that adorned a generous belly, promptly forgot the name of the woman he was tasked with thanking. Unamused she took over and sternly instructed the dancers not to get drunk but to follow the example of their ancestors and drink wild honey.

I think Fanta was the happy compromise.

Disappointingly for many Australians, the Voice referendum last October saw 60% of votes pitched against further constitutional recognition of First Nations people. The slogan ‘If you don’t know, vote No’ was eerily reminiscent of some of the Brexit referendum tactics (ahem…lies) that particularly appealed to ignorance or those who felt left behind.

Nonetheless, in certain places in WA and no doubt all over the continent, I found sincere apologies for Australia’s past treatment of its first people. An Island off the coast of Fremantle, just south of Perth in WA, is one such place.

Between 1838 and 1931 the beautiful island of Wadjemup, also known as Rottnest Island, served as a prison for approximately 4000 Aboriginal men and boys from Western Australia. At least 373 of these prisoners died in custody and were buried in an area currently referred to as the Wadjemup Aboriginal Burial Ground. Many of them were leaders, law men and warriors, the guardians and carriers of a nation’s knowledge and stories. Their absence created turmoil in their communities and a sense of loss still felt today.

For decades, insensitivity towards the plight of those prisoners and their families manifested in the decision to transform the Island from an Aboriginal penal settlement to a recreation and holiday destination. As part of this transformation, the area where the burial ground is located was repurposed as a camping ground known as Tentland, and the Quod (main prison building) was converted into a hostel. As in so many countries the world over, the painful history of the Island as a place of incarceration was concealed.

Tentland was only closed in 2007. The Quod hostel now lies behind locked padlocks.

On November 6th, 2021, the Rottnest Island Authority (RIA) Board delivered an official apology to the Aboriginal people of Western Australia for their role in ‘the obfuscation’ of the prison history and the disrespect of past practices:

“We recognise that this has caused great pain and anguish within Aboriginal communities. For this we apologise…. We will continue to work in collaboration with the Whadjuk Noongar people and the wider Aboriginal communities of Western Australia to promote reconciliation and acknowledge the past.”

I can imagine this has been welcomed by most, though it was distressing to visit the excellent little museum only to find the banging music and loud voices of a surfing film drowning out the important and deeply moving – when you could hear them – testimonies of descendants of the those imprisoned here. And while the little port hummed with ice-cream-licking tourists on bicycles, I found myself completely alone walking the periphery of the nearby burial ground, following the instructions of intermittent signs reminding you that the spirits of those who died remain here among the trees, part of the island.

Listen for a moment.

See and understand.

The spirits of the land

are speaking. Listen…

Kwidja baalap yey – The past is still present.

Our world is full of conflicts based on collective blame, attributions of guilt and/or a need to redress a national humiliation or wrongdoing. Such a binary dynamic is eternal, cyclical and as old as the world. Admissions of guilt accompanied by apologies are rare and largely avoided for multiple reasons, from not wanting to lose face or moral high ground to fearing being landed with restitution and reparation costs. Retrospective apologies are frequently considered hollow or politically motivated. So what options does that leave?

Australia’s example will be considered by many as flawed and insufficient; too little too late. But the country’s efforts to recognise the pain inflicted is surely better than ignoring its lasting impact. The visionary Ngarinyin lawman David Banggal Mowaljarlai offers us a way forward. Born in 1925 on the Kimberley coast, he lived a traditional life but became adept in both cultures becoming, among other things, a Presbyterian lay minister, a painter, a social justice advocate and a land rights activist who then travelled the world as storyteller, thinker and educator. “We are really sorry for you people,” he said in one of his many broadcasts to ‘whitefellas.’ “We cry for you because you haven’t got meaning of culture in this country. We have a gift we want to give you… it’s the gift of pattern thinking.”

When I read this is Tim Winton’s ‘Island Home,’ (p.231-3) it clarified to me what I have always loved about Aboriginal art: the innate interconnectivity between human beings, nature and the universe that run far deeper than any divisions of nationality, colour, language, religion etc. Mowaljarlai’s ‘Two Way Thinking’ is a philosophy of mutual respect, mutual curiosity and cultural reciprocity. The uniting principle of ‘mutual obligation’ that became a catchphrase loved by politicians, of course extends to the natural world. To me it offers a genuine way forward that transcends any hopelessness and helplessness we might feel towards the huge problems we all, as a human race, are, or will be facing.