Spring is Nature’s childhood. It’s frequently associated with youth, new beginnings and innocence. Yet while blossoms skip through our outdoor landscapes, our screens highlight with renewed urgency the premature loss of innocence of our younger generations with devastating consequences to their mental health, education, relationships and identity.

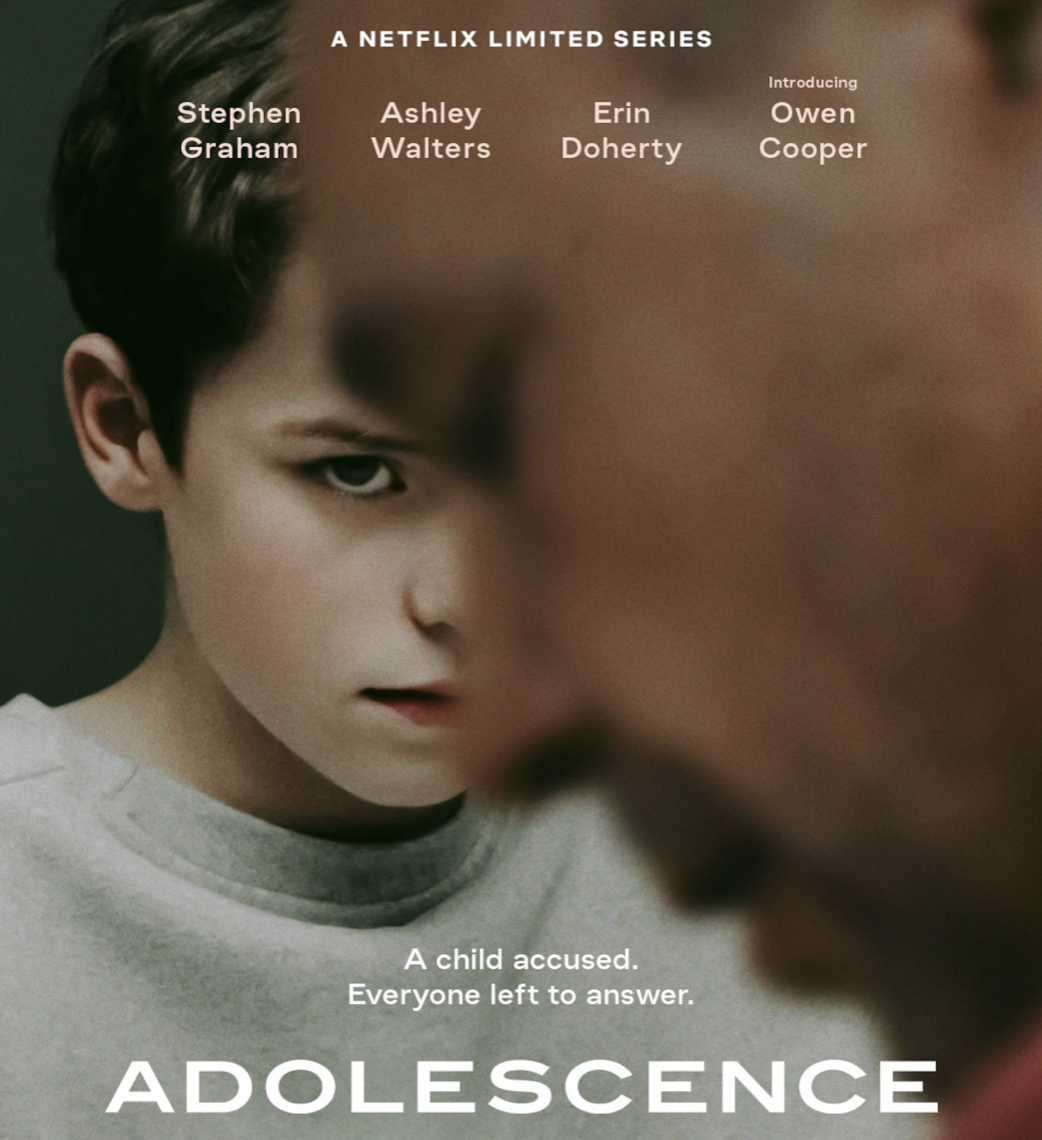

With that in mind, I was going to write about the new Netflix series, Adolescence, that has provoked widespread debate and concern about toxic masculinity, the ‘manosphere’ and sexist ‘manfluencers’ like Andrew Tate. (If you haven’t seen it, I can only encourage you to do so). Online platforms and social media are abuzz with it. Even Radio 4’s Moral Maze dedicated its weekly slot to exploring the question: What’s wrong with men?

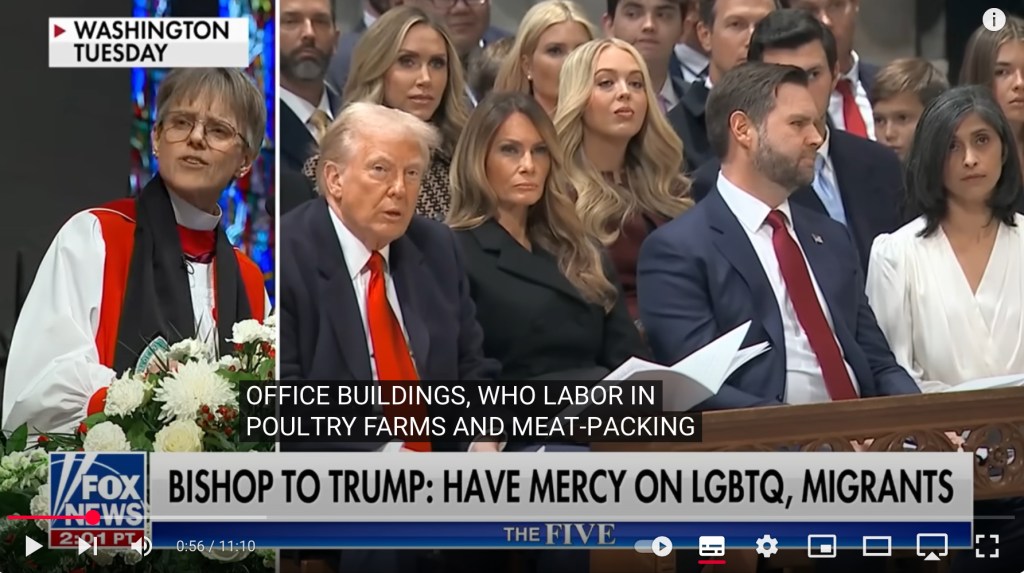

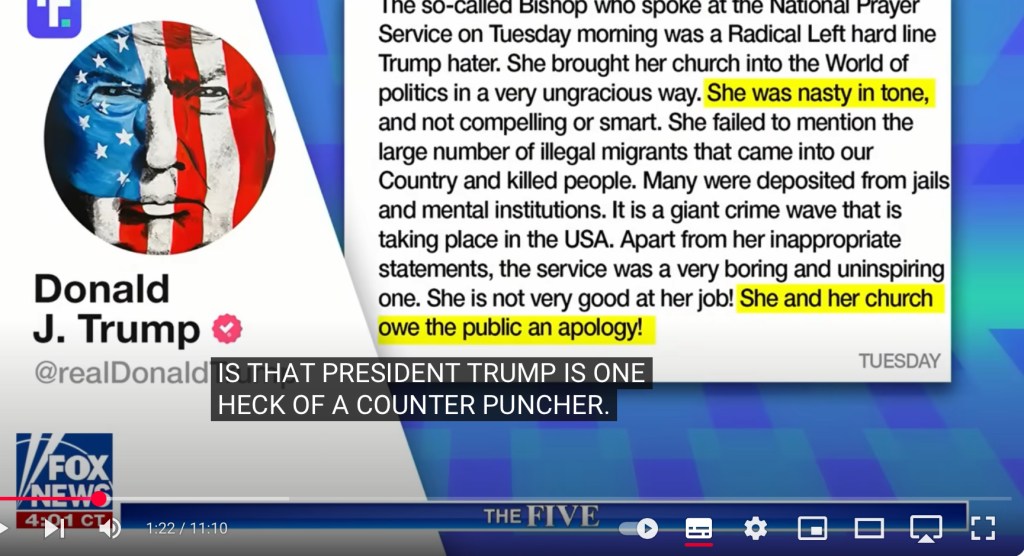

Plenty more such questions could be asked in relation to the various world leaders dominating our headlines – Trump, Putin, Zelenskyy, Netanyahu, Starmer, Pope Francis – who between them are presenting a smorgasbord of appealing to repellent aspects of maleness.

I also considered writing about my recent visit to one of London’s dilapidated prisons – organised by the wonderful charity Prison Reading Group – to deliver a session on my book to a group of male prisoners who had read it. About the lingering impressions I’m left with, both of the shabby, four-storey wing that looked, smelt and sounded like your worst imagining of incarceration, and of what happened in the tiny room embedded in it that offered space for our inspired conversation. As always, I was touched by the men’s deep grasp of the themes I address in In My Grandfather’s Shadow, their carefully prepared lists of insightful questions, their gratitude for the positive impact the book had made on their lives. As always, I felt intense frustration at a system of wasted opportunity, money, time and human potential. As always, the wounds left by the absence of fathers, positive male role models and the learned ability to deal with overwhelming emotions glared red.

But in the end, I couldn’t face writing about any of these huge and complex topics, even though they occupy my thoughts.

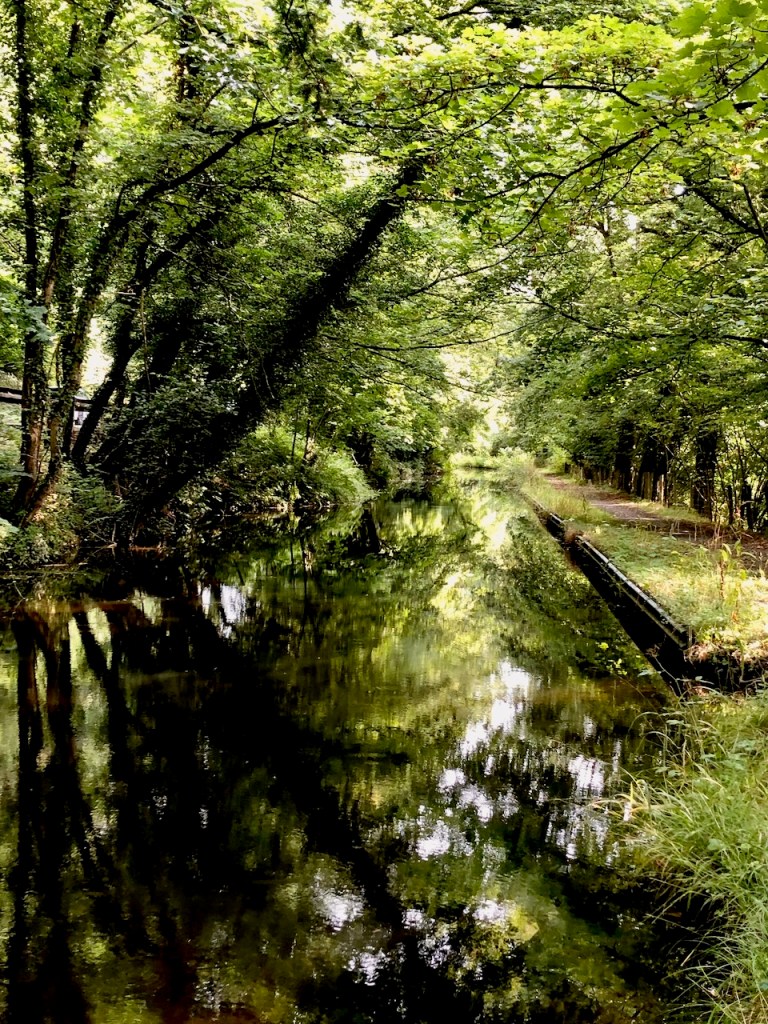

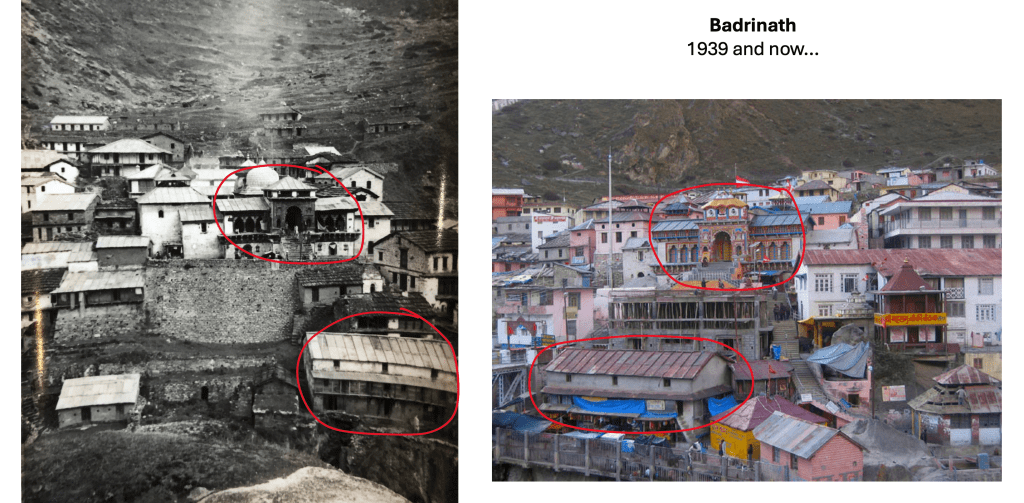

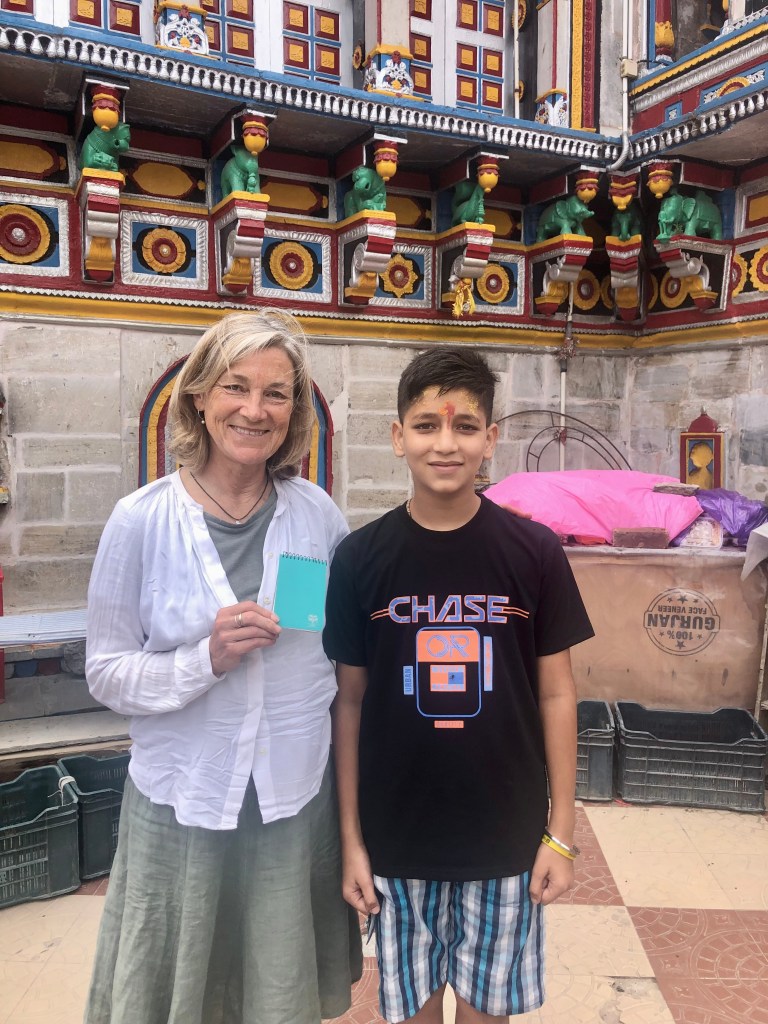

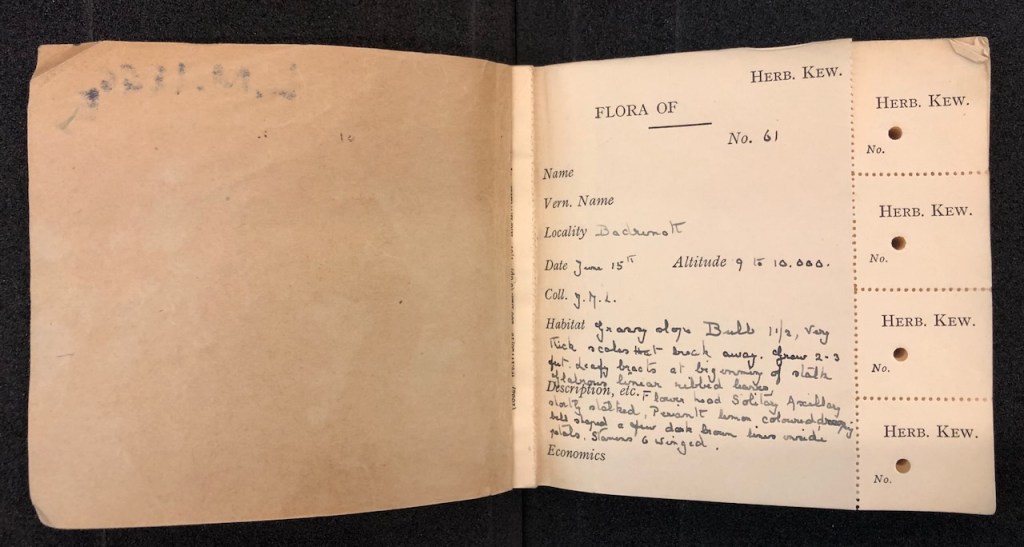

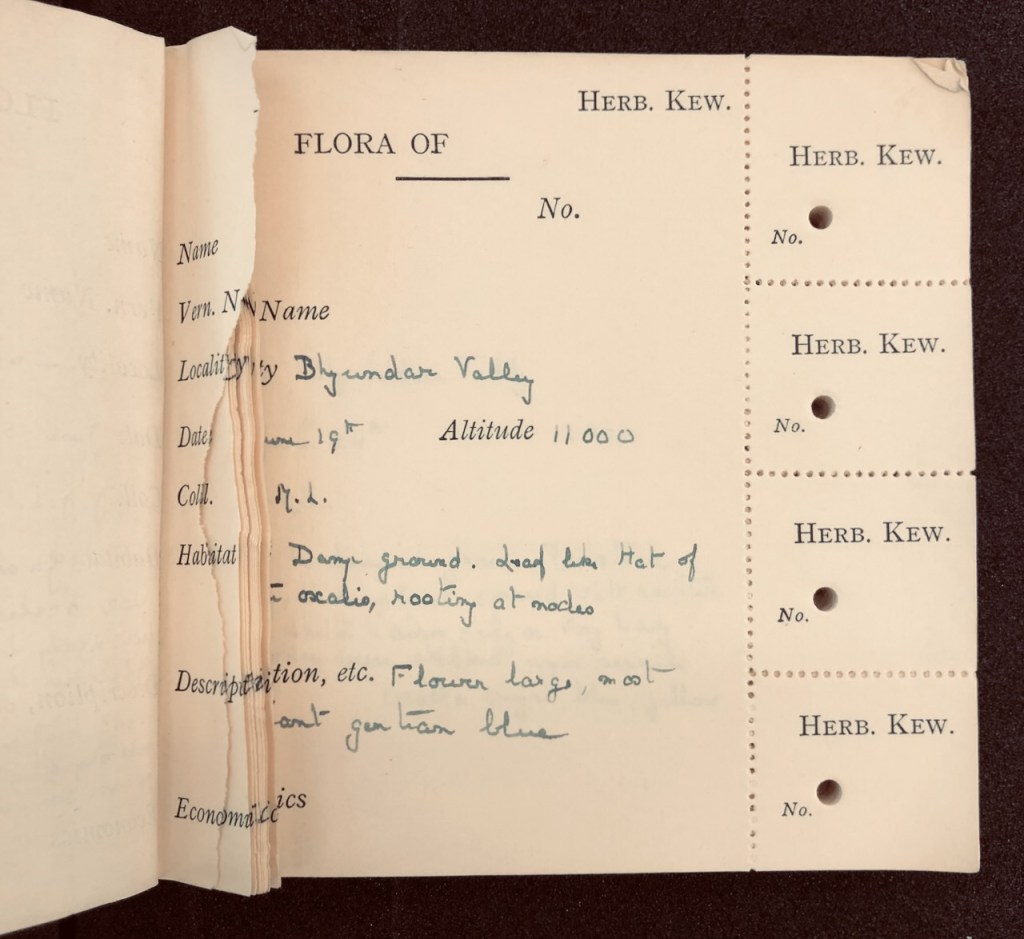

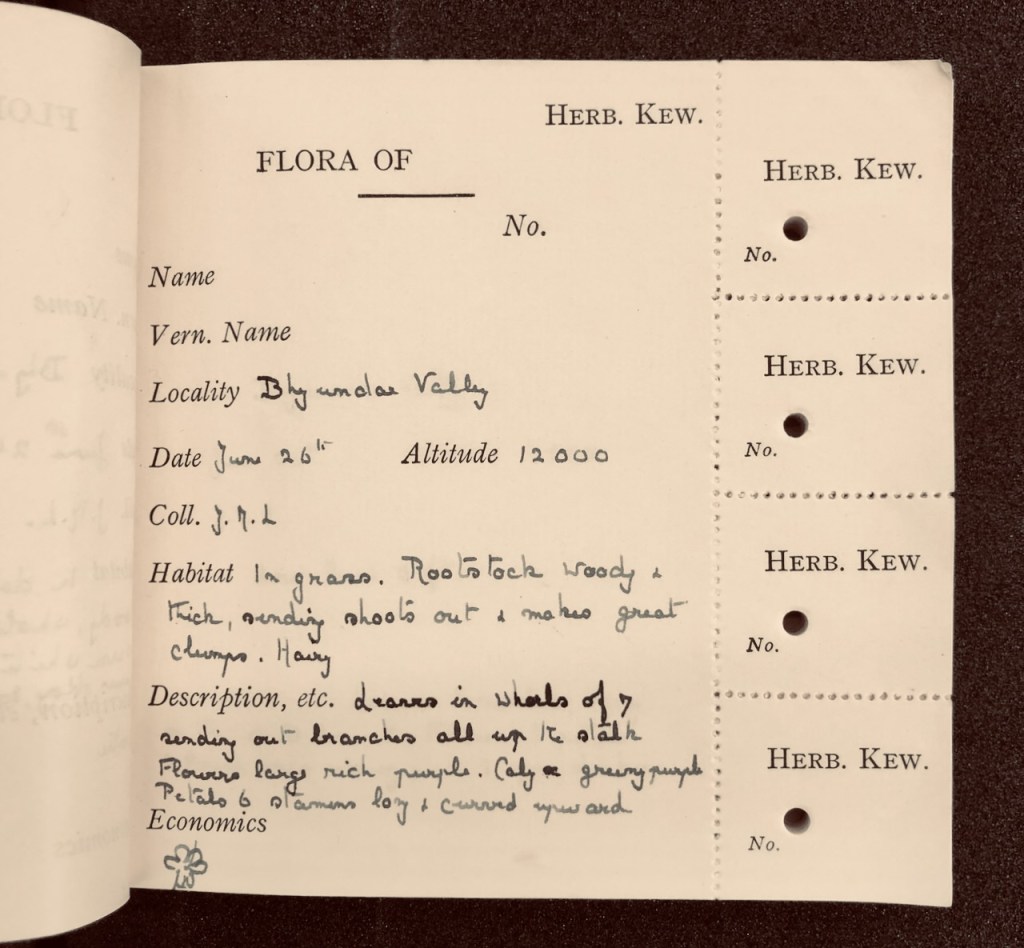

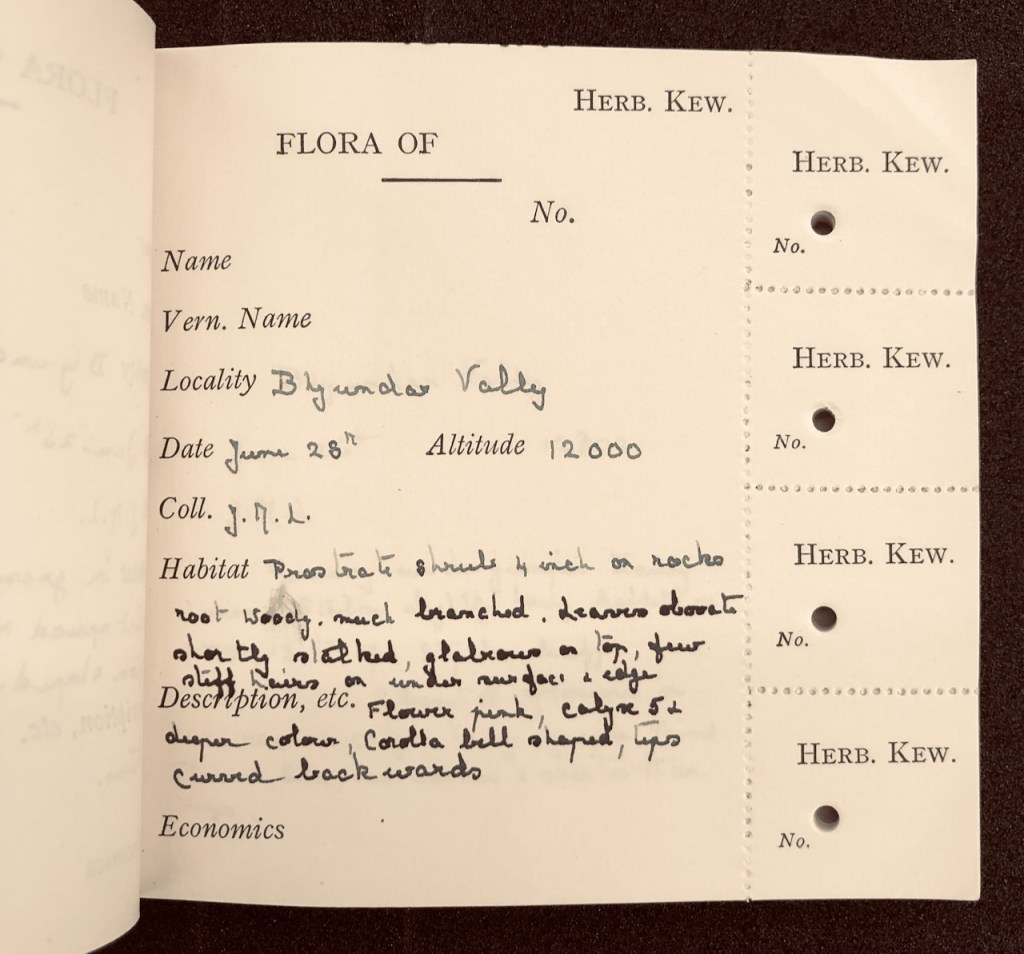

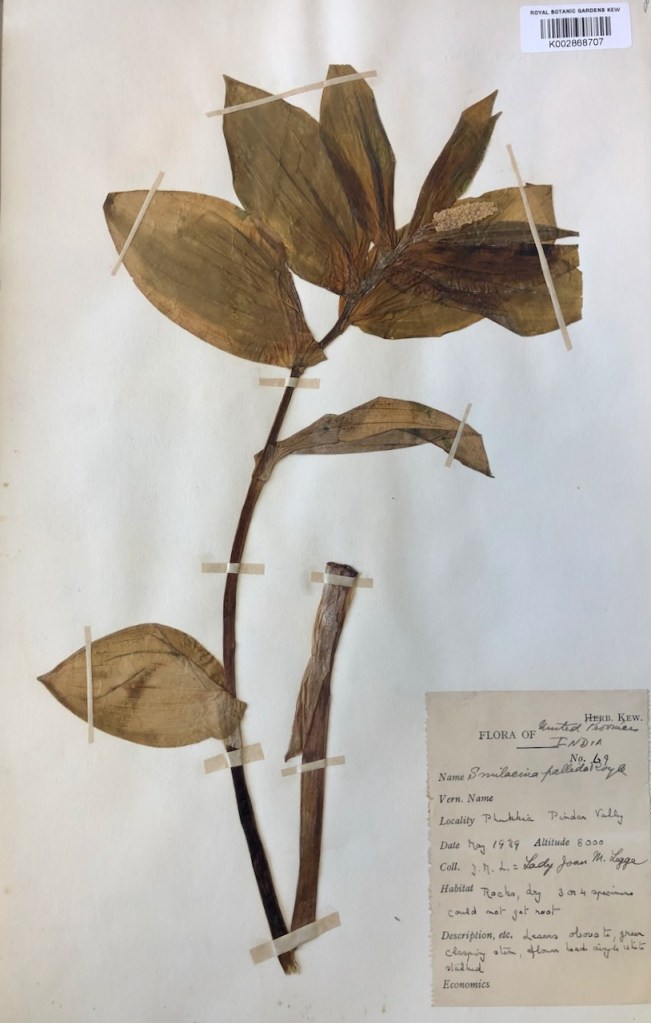

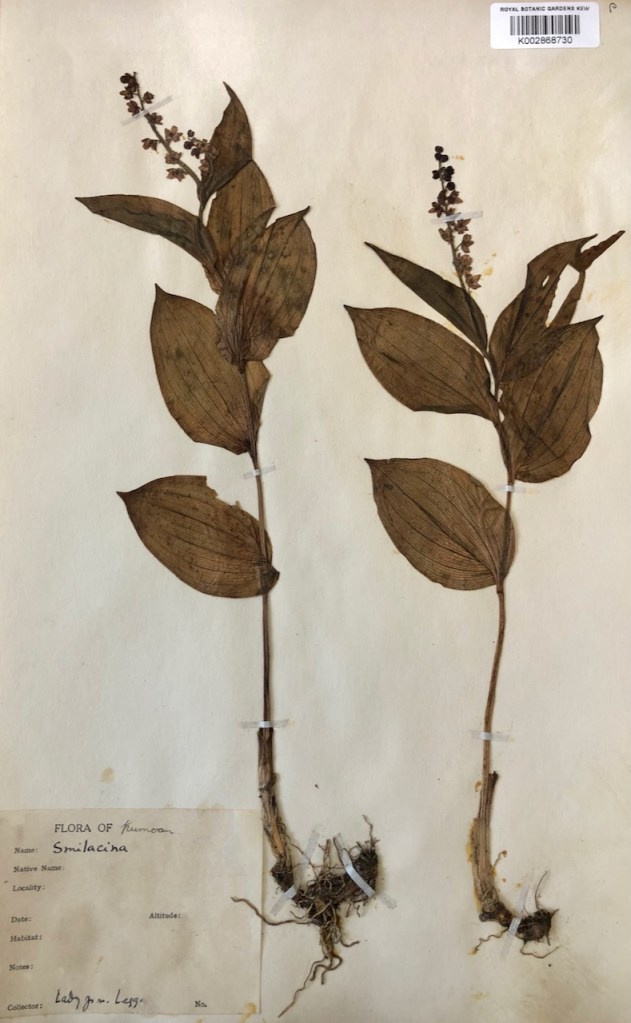

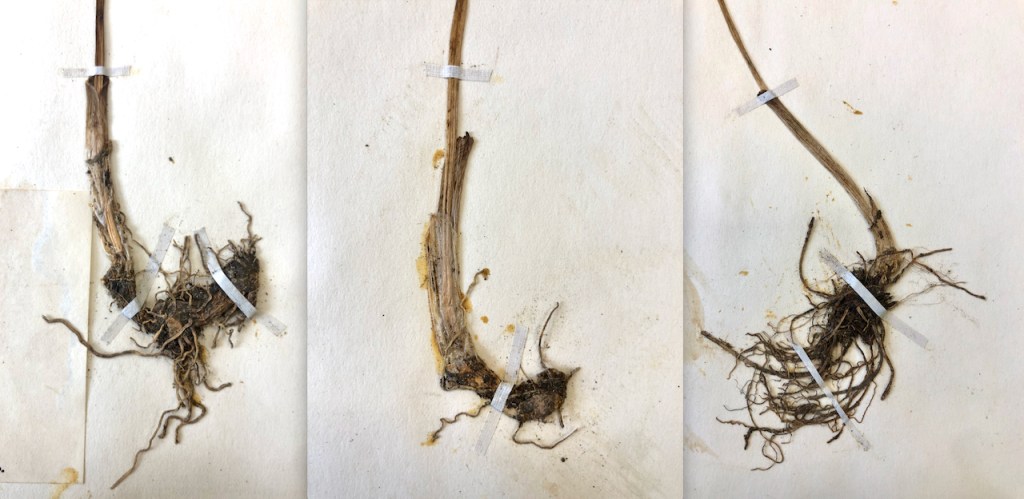

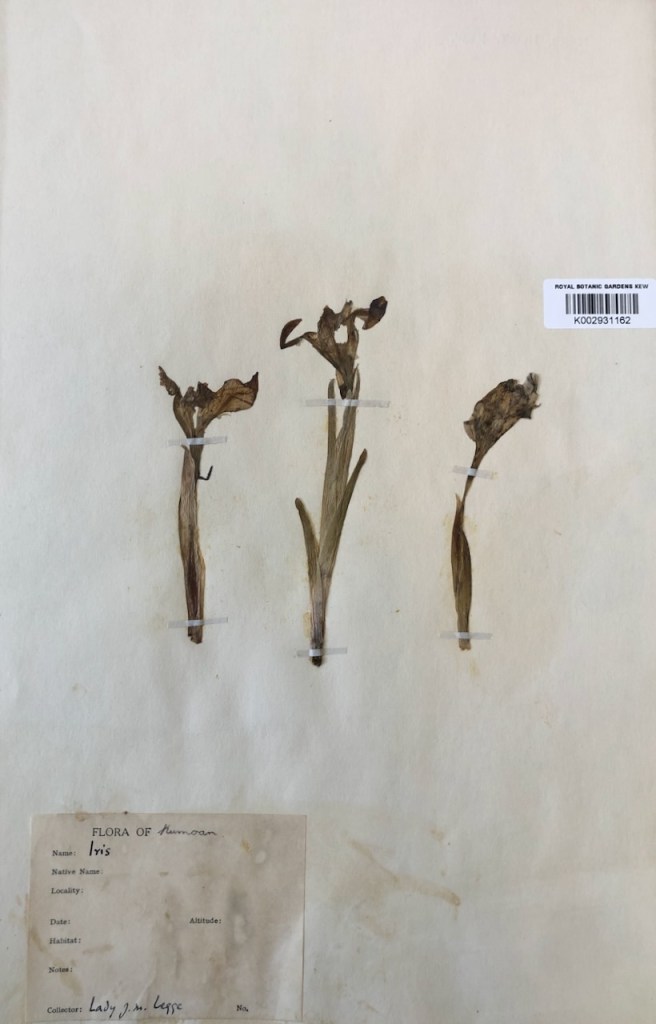

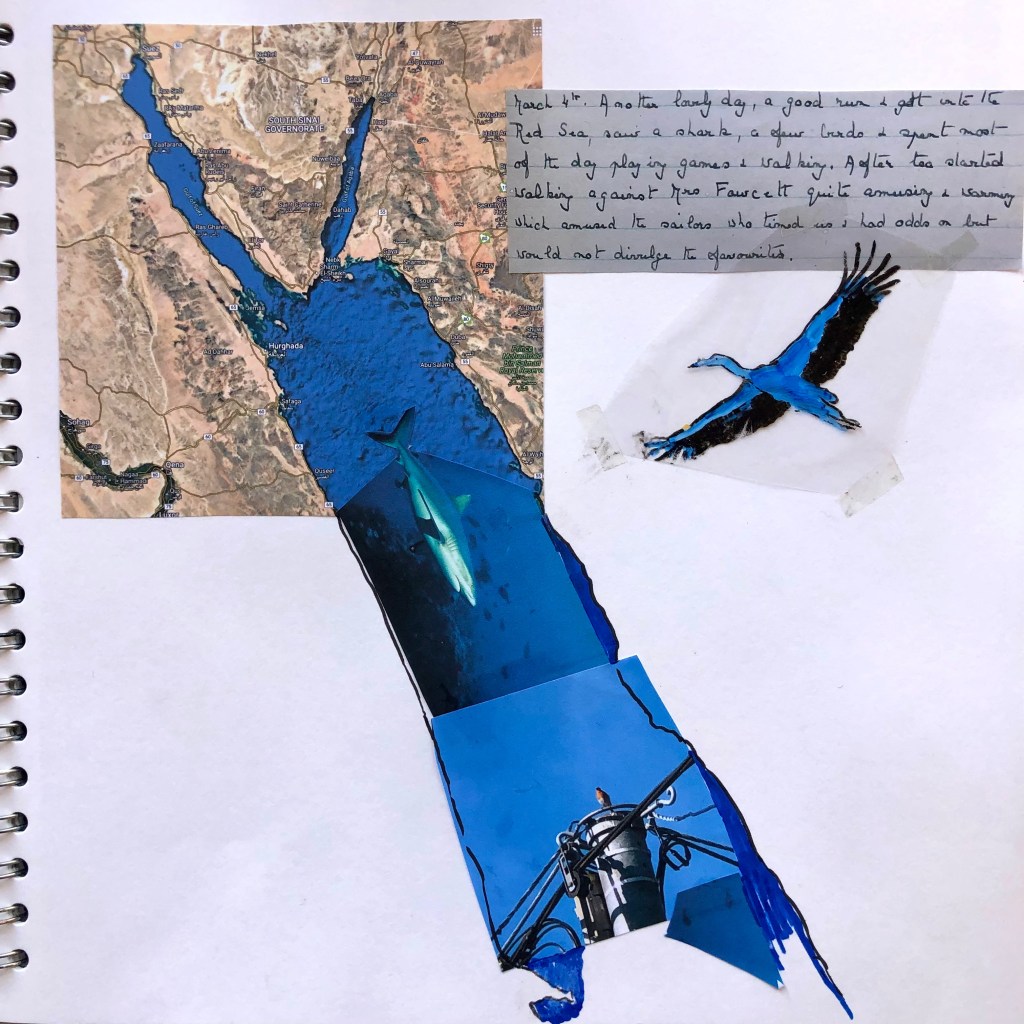

Instead, I find myself once more turning my focus to the more uplifting emergence of spring flowers both in nature and my garden. And to my inspiring great great aunt who travelled to India to gather floral specimens for Kew Gardens and in whose steps I am metaphorically walking for the next few months, following her diary as she sails from Birkenhead to Mumbai and then trains it up to the Himalayas. Each day I am reenacting a small action or activity she did in 1939, taking a slightly oblique photo that relates to it, posting it on Instagram (angela_findlay) and then creating an experimental collaged page in my sketch book. It’s my way into telling her story.

From 17th February to 13th March she was on board the T.S.S. Hector cruise ship playing quoits on deck or holed up in her cabin feeling seasick. (Not easy to make ‘art’ out of either!) There followed a few ‘outstanding’ days in and around Colombo visiting tea plantations and paddy fields, another sea voyage and several trains to the small hill station of Ranikhet in Uttarakhand. This will be her base for several months as she acclimatises, goes on practice treks and waits for the snows to melt further north giving her access to her ultimate destination, The Valley of Flowers.

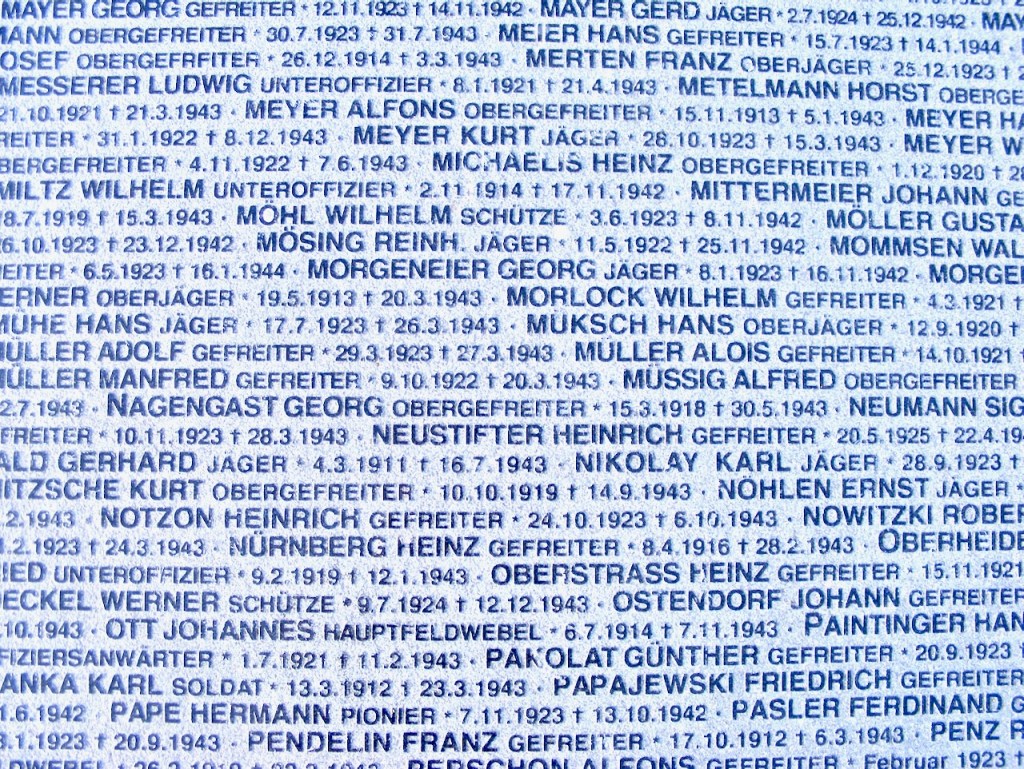

With deep regret I am coming to accept that I am not one of those exquisite botanical painters whose sketch books are veritable works of art. And I am sorely lacking in the plethora of technological and digital tools that are creating mind-blowing new universes in the art world. But I find solace in the fact that like Joan, I too am on a journey towards a (in my case, artistic) destination unknown, exploring and accompanying this intrepid female relative on her solo adventure. Ironically the worldly backdrop to her trip are the precarious months leading to the start of the Second World War. Mine is the run-up to the 80th Anniversary of its end. Or, if stupidity and egos escalate in the wrong direction, the beginning of the third…

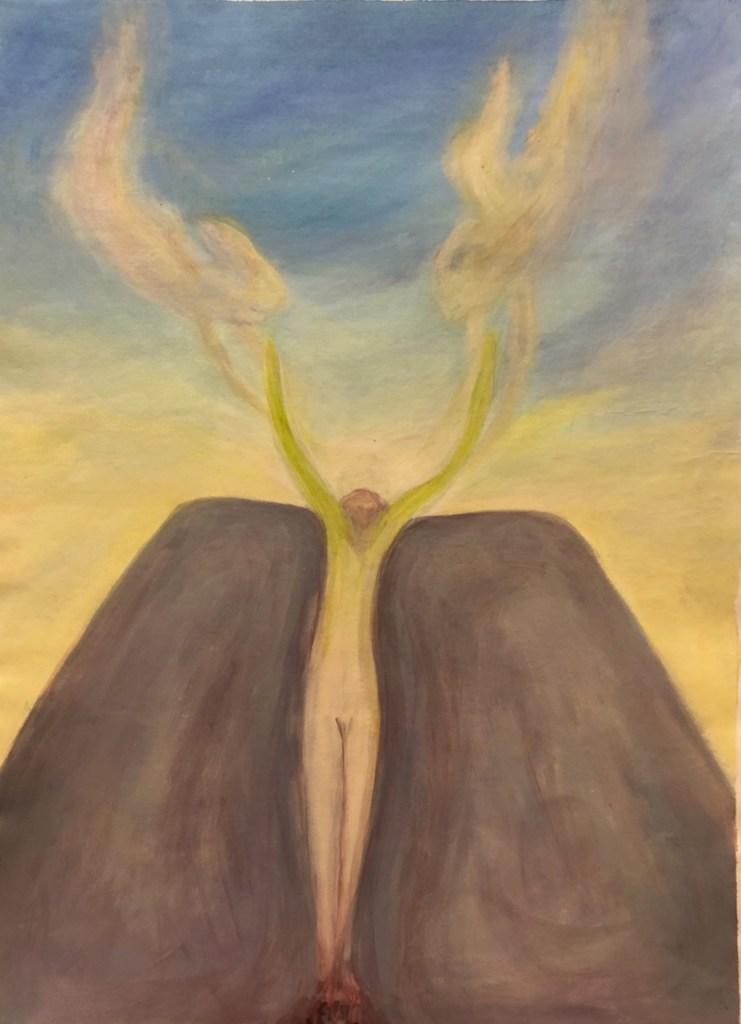

War, the word alone snaps me back to present reality. I imagine we are all treading this fine line between engagement with the wider pain and travails of so many and the small (and big) joys and concerns that can be found within our homes and lives. How to care and act without losing sight of the beauty and wonder constantly available to us? How to engage with the immeasurable force of Nature’s creativity rather than human beings’ destructiveness? How to stay awake and feel, but not succumb to anger or blame?

It’s an on-going practice… a dance. And Spring feels like a perfect time to take to the floor.